When it first became clear that we would almost certainly not have a debate this week, my thoughts immediately went to the debate’s erstwhile moderator, Steve Scully. The 14th of 16 children, it was finally going to be Steve’s moment in the spotlight. And you should all be so lucky to have someone like Steve in your life, as he is one of the two kindest and most generous people that I have met in this town.

So in lieu of a debate, I thought I’d talk to someone about what it’s like to moderate a debate. And who better than the inimitable Ann Compton—the one person who might, in fact, be the most kind and generous person in D.C.

She doesn’t know this, but before I first met Ann, I called a former colleague of hers to get tips on how to impress her and I even planned out my outfit so as to look “casual but put together.” I wanted so badly for this towering journalist not to think I was a total hack. When I finally got to meet her, before I could say anything, she rushed over and said “you must be Sarah” and gave me a big hug. Since that moment, we have had pajama parties, lots of long lunches, and at least one socially distanced “Fauci pouchy” of rosé on her screen porch so she could be the first person to meet the Brisket outside of our house. Ann mentors so many women in this business that I am far from alone in feeling this way toward her.

After 40 years, Ann retired from ABC News in 2014. She covered seven presidents and was a panelist for both a 1988 and 1992 debate. And, boy, does she have stories.

Sarah: How does one get selected to be a debate moderator?

Ann: I was twice on the panel back in the old dinosaur days when it was three journalists plus a moderator. The moderator only got to ask the first question and then kept a stopwatch and the three journalists were the ones who thought of all the questions.

In 1988, I was on a campaign plane covering Lloyd Bentsen, the vice presidential candidate on the Democratic ticket. And we were about to take off in our little campaign plane from Allentown, Pennsylvania, when the pilot got a call that he had to stop and come back to the terminal. Ann Compton had a phone call waiting for her.

Sarah: Oh wow.

Ann: I get off the plane. The candidate, the staff, the whole press were waiting onboard. I go in and I literally drop a quarter into a payphone, and I call a number in Los Angeles. The executive producer that year, Ed Fouy my former boss, is on the other end of the line and says, “Ann, the Commission on Presidential Debates would like to invite you to be one of the three questioners on the debate 48 hours from now.”

And I said, “Well, I’ll have to check with my office and ask them if that’s all right.” He said, “Please do and call me right back.” So another quarter and I call New York. Of course, the executives at ABC were all sitting around the phone knowing this was coming. They said, “Is it to be the moderator, or a questioner?’ I said, “It’s to be on the panel, a questioner. And they said, “Yes that’s fine, yes absolutely do it.” So I call Ed Fouy back and I get back on the plane. Bentsen knew this was coming, his press secretary Mike McCurry knew this was coming.

Back in the 1980s, when this whole Commission on Presidential Debates system was rather new, it was decided by the debate commission. They did run names by the two campaigns to see if these potential participants were okay. Sometimes they’d let a campaign veto somebody. But then the Commission on Presidential Debates extended the invitation. And it literally was on an afternoon when the debate was not that night, but two nights after.

Sarah: Yeah. Wow. So how did you prepare with so little time?

Ann: We were all flying blind. We had no instructions, other than the debate format—you know, two minute answer, 30 second rebuttal, the opening statement. We had no instructions on issues, or where we would sit, or how we would do this.

The three questioners and the moderator were booked flights to Los Angeles from Washington. I went first thing the next morning, and we were each checked into this little boutique hotel in Beverly Hills somewhere where we were supposed to be absolutely anonymous. No one was supposed to be able to get near us. I opened my hotel room, and stacked up at the door of my hotel room, are emails, magazines, notes, letters from people wanting to suggest questions. So our location wasn’t that secret.

This was the last debate between George Herbert Walker Bush, the vice president of the United States, and Michael Dukakis, the governor of Massachusetts. The last one on October 11 or 12, and the three questioners were all women: Andrea Mitchell and Margaret Warner and me.

Sarah: Is that the first time that had ever happened?

Ann: You know, the system hadn’t been around for that many years, so it was the first time. I always assumed there was a male questioner that somebody vetoed and then they called me. But I don’t know, nobody ever goes into that.

So, we decided that we would like to get together and make sure we had enough questions. Peter Jennings, the ABC News anchor, had been a questioner on the panel for the vice president debate that year. And he called me and said, “Annie, make sure you have enough questions. You have to go for 90 minutes with no breaks, and we all showed up and we all had the same six questions.” I said, “That’s a great idea, Peter.”

So I said to Margaret Warner and Andrea Mitchell, “Let’s meet in my hotel room in the morning, and I’ll order coffee, and we can make sure we have all the bases covered.” And I turned to Bernard Shaw of CNN. And I said, “Bernie, would you like to join us?” “No,” he said, “we are professionals, we don’t write each other’s questions. No, I won’t.”

So that morning. The three of us met in my hotel room—coffee and danish—we were literally in our pajamas and fuzzy slippers. And we had yellow pads and Andrea Mitchell wanted to be sure to ask about the nuclear triad and Margaret had something on foreign policy. And I said, “Wait, we got to ask about the Supreme Court.”

So we went through all these things. “Do you want that one?” or “Oh, I’ll take this one.” So we didn’t really have it mapped out as to order or anything but at least we knew we had more than enough material.

All of a sudden there’s a knock at the hotel room door. It’s Bernard Shaw. He came in and says, “I’m not going to tell you my first question.” I said, “Well, Bernie that’s okay”—I was the first question after the moderator—”I’m gonna ask George Bush about ‘read my lips no new taxes.’” He said, “okay,” and he goes over to my windows and pulls all the curtains closed. He says, “You never know. Those campaigns might be out there trying to listen to everything we’re saying. We got to be massively over careful.”

So finally Bernie sat here and we finished all our conversation. We didn’t tell him everything we had. He just listened for a little bit and then said, “Okay, I’m going to tell you the question.” And he said, “I’m gonna start with Governor Dukakis. If Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered, would you still [oppose] the death penalty?” And the three of us looked at each other. And I think Andrea said, “Oh God, that gave me chills, gave me goosebumps.” And Margaret said, “Don’t you want to take her name out of it or something?” We argued with him to change the question. He wouldn’t do it. Three times that day we tried to get our moderator not to ask that question, but of course, he did.

So that is the extent to the preparation and the coordination between the three panelists and one moderator, who got only the first question.

But that was the extent of it. We had like 36 hours for each one of us to give this the thought necessary, and no real time to do homework because most of the time was spent on an airplane getting to Los Angeles.

Sarah: In the intervening 30 years, I bet you’ve talked to many debate moderators. What is the biggest piece of advice that you give them?

Ann: The problem with debates is not the rules. It’s not the little details. The problem for the moderator is having to look up at a candidate or two candidates—or in another case, three candidates I did in the next debate. The problem with the debates is not the rules and the little minutiae. The problem is having one or more candidates who don’t want to come and discuss issues. The candidate is there to perform. And that’s what makes it so difficult.

Sarah: If you could wave a magic wand, how would you change presidential debates for 2024?

Ann: I have thought about this long and hard. My dream debate is a darkened stage with a round table in the middle, and two chairs facing each other. And there’s an audience in the dark. As the lights come up, the Republican candidate comes from the wings on one side and the Democrat from the other. They come out and sit in on opposite sides of this small round table. And they start to talk. And at about 55 minutes into it, an announcer—the voice of God announcer—from the rafters says, “You have five minutes remaining.” The two of them finish their conversation. They stand up. They shake hands, and they depart.

[Long pause as I laugh so hard I make myself cry.]

Ann: I want the transcript to note that the interviewer laughed hysterically when I explained that.

Sarah: Oooookay, what do you think the chances of that happening are, Ann?

Ann: Slimmer than none. There is no perfect debate format. There are no perfect debate moderators or questioners. There are no perfect candidates. I do think that from my point of view now that I am a debate consumer, not participant, the best format for me as a consumer, picking up my mind between two or three candidates, is the town hall debate.

The biggest flaw of a town hall debate is that there may be 20 average citizens representing diversity, but I have never felt that they are really all undecided voters. And I think each one of them does have a point of view. But a town hall debate with undecided voters is to me the most informative hour or hour and a half.

Sarah: Do you think we’ll have presidential debates after this cycle?

Ann: I am sure that presidential debates for not only the general election but for the primaries will continue. And I think they may morph into different creatures. The journalist panel I think is a dinosaur. I don’t think we’ll see that again. But there is something to be said about having impartial journalists be the ones asking the questions.

Primary debates are a totally different bag because it’s so many candidates, and they are striving for attention. I think it is vital for American politics that the nominees of the major parties come together in goodwill to discuss issues in every presidential campaign, whether it’s under the debate commission which is run by Republicans’ and Democrats’ establishment party officials, or whether it’s done under the aegis of a university or a news organization. But I think they’re absolutely vital for the American voter.

Sarah: What about the problem that has affected politics maybe the most of anything I’ve seen in my lifetime, which is people getting their news increasingly from either partisan sources or separate sources based on their partisanship. And the result is that now the debate moderator is now almost equally a participant in the debates. So much so that viewers are often judging the moderator more than either of the two candidates and/or believe that the moderator is biased against their chosen candidate.

Ann: You have just hit on two issues, which show how important that face to face debate should be. And why I like the idea of letting the two candidates—if they can behave themselves—talk to each other. The reason it is so important that the two candidates go to a structured debate of some sort during the general election is that is the only place all of the interested voters can see both of them on equal footing. Same, same place, same issues. Not only do Americans go for their news in their own comfort zone. But they get their own choice of what they want to know about the two candidates. And their own choice on what they want to believe in campaign advertising. And there is no journalist on the face of the earth, including the dearly departed Jim Lehrer, who is going to be regarded by everybody as a total honest broker. They just don’t exist.

Sarah: Ok, last question. What was a non substantive thing that you were most nervous about going into those debates—whether it was that you would sneeze or that your shoes were uncomfortable. Or whatever.

Ann: As I sat down in those chairs at those two panel debates, what I was least worried about was what I was wearing. The one where I sat with only women, I wore a black knit dress because I knew everybody else would be bright colors. The second debate, I was the only woman with three men. And I went out and bought a bright Air Force blue St. John knit dress knowing I would be the only one wearing a color at the desk.

What I worried about was my mascara running. Because you get your makeup on at least a half an hour before the program starts. You sit down under hot lights for 90 minutes. You do not have a Kleenex to dab around your face if you get hot. You don’t have a way to check to see if your hair’s falling in your eyes or your lipstick gets smeared. You don’t have any way to judge it. You have no TV monitors. You cannot see any of this. It is just you and the candidates in person.

So what I was most comfortable with was dressing for the stage setting that I would be sitting on. And what I was most worried about is under the hot lights, my mascara running all over my cheeks.

Sarah: Were you ever nervous?

Ann: I never got nervous … until it was over. You run on adrenaline. And it’s over. You go out and you call home and all my four little kids were allowed to stay up and watch mommy on TV—primetime—and the oldest one who was 8 said “Mommy, more people saw you tonight than saw the movie Star Wars.” At that moment, fear went like electricity through my body.

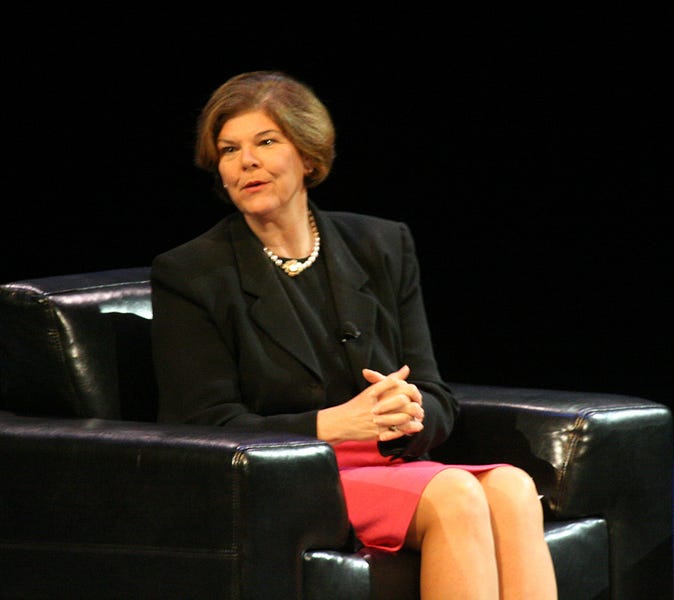

Photograph by DBKing/Wikimedia Commons.

Sarah: That’s a great way to end.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.