Campaign Quick Hits

Where the RNC’s head Is At:

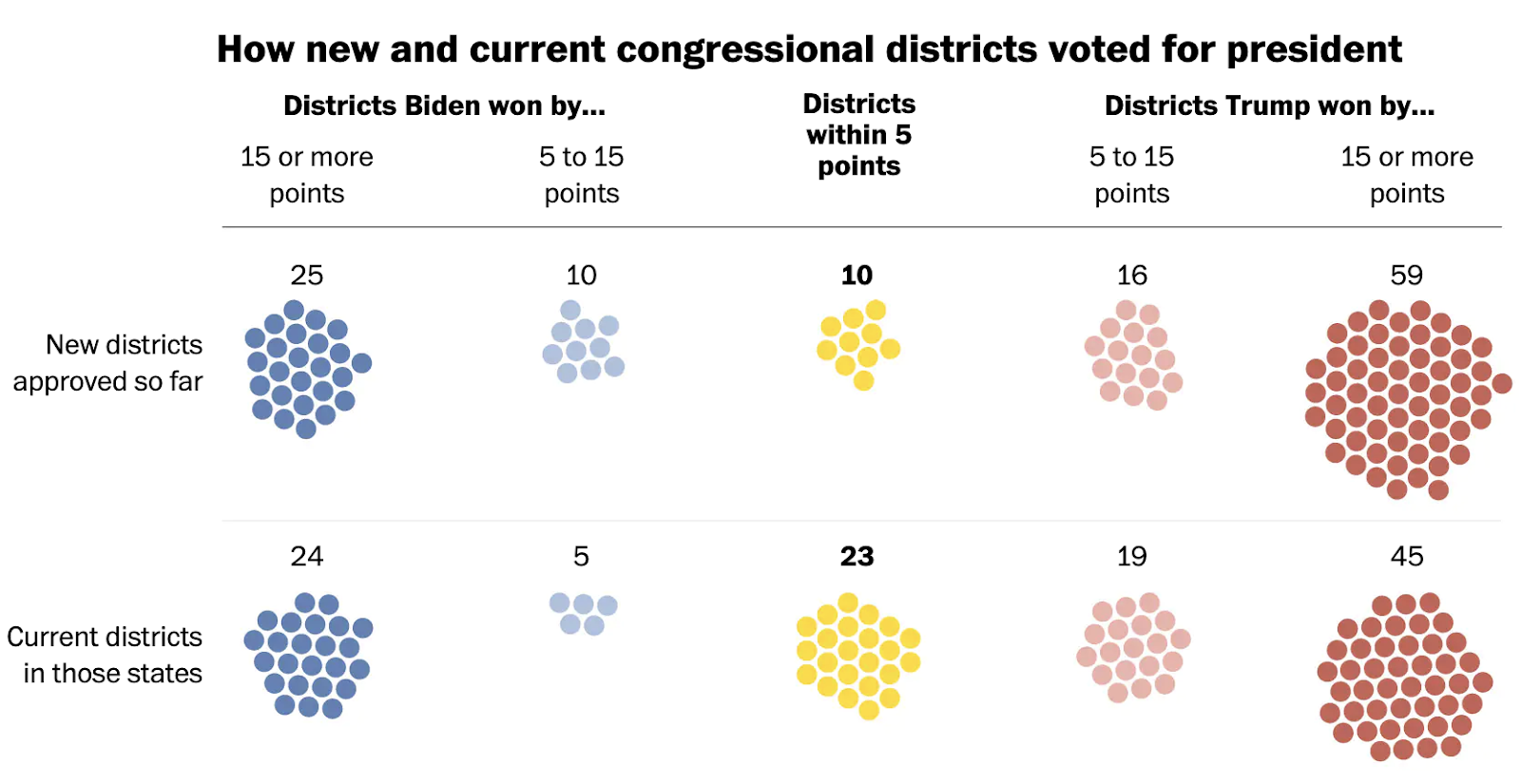

How Redistricting Is Going: Well, this kind of sums it up: “The new map in Texas would reduce the state’s 12 existing competitive districts to one.” But just in case you need to see competitive house districts disappearing in picture form:

Post-Virginia Autopsy for Democrats: Center-left think tank Third Way released its report to Politico after focus grouping Democrats in Virginia after the loss a few weeks ago: “Voters couldn’t name anything that Democrats had done, except a few who said we passed the infrastructure bill.” And while they found that Biden voters “do not necessarily blame him for ongoing problems with the delta variant, inflation, or supply chain bottlenecks … these 2020 Biden voters had little positive to say about him right now, and many described disappointment or a sense that he is not doing well. They were reluctant to say he’s not up to the job, but they don’t feel like he’s getting it done right now.”

Like Republicans post-2012, Democrats are too willing to argue that this all comes down to a messaging problem. As someone who was at the RNC for the 2013 “autopsy,” which found that the Republican Party needed to increase minority candidate recruitment, soften its rhetoric on immigration, and invest in voter outreach, I can’t help but wonder if Democrats are making the same mistake.

Reince Priebus in 2013: “To be clear, our principles are sound, our principles are not old rusty thoughts in some book but the report notes the way we communicate our principles isn’t resonating widely enough.”

Megan Jones, a former Harry Reid adviser and Nevada-based Democratic consultant who was quoted by Politico in its focus group reporting, said Democrats are “doing a ton of stuff, but we’re not communicating it well.”

Beware blaming the messaging. Sometimes, it’s the message.

Codebook: Kristen Soltis Anderson, friend of the newsletter and godmother to the Brisket, launched her own great data-driven newsletter, Codebook, that you can sign up for here. Last week, she included 100 facts you need to know for the midterm. Here’s a taste of Nos. 8 and 9:

8. In 2009, one year before the “Red Wave” election that saw a net 63 seats flip Republican in the House, the ABC/Washington Post poll saw Republicans hold a 3 point lead on the “generic ballot” – the question of which party’s candidate people would rather vote for.

9. Their most recent poll has Republicans with a 10 point lead on that same question.

Wowzer.

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs—but Not Anymore

Thinking back to Bill Clinton’s “it’s the economy, stupid,” campaigns have always been about the bottom line for most voters. And while “economy” may be a flimsy term, most candidates have always translated it into terms of “jobs,” “job creation,” “take home pay,” “wages,” etc. But 2022 is going to be different.

Just look at Nebraska. As of last week, there were 69,000 job openings in the state, but less than a third as many people seeking work, according to the Wall Street Journal. Unemployment in Nebraska is down to 1.9 percent. And, yes, as any Cornhusker will tell you, Nebraska is special—but even the national jobless rate is only at 4.6 percent. (For those who are thinking this is just people no longer actively looking for work, Nebraska’s labor-force participation rate is down less than 2 percent from its pre-pandemic highs.)

All this means that “the economy” isn’t going to mean talking about jobs for a lot of people in 2022. In fact, a lot of Americans are leaving their jobs—more than 4.4 million in September—in what’s being termed the Big Quit. This, in turn, puts increased pressure on businesses that can’t find employees. They can raise wages—and in fact wages did rise 4.9 percent year over year in October—or they can automate, meaning those jobs aren’t coming back.

Wage growth can be a good thing, of course. But large data can be misleading. Take home pay isn’t going up for everyone, and it isn’t going up evenly. As Betsey Stevenson, professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan, explained to Marketplace:

Wage gains are disproportionately happening at the bottom of the income distribution. They’re also disproportionately going to young people, people under the age of 25. And they are disproportionately going to millennials who change jobs, not those who stay in their current job.

And as we all know now, supply chain issues coupled with wage growth can drive inflation. And the expectation of inflation can drive wage growth.

Which is all to say, listen for shifts in the normal economic messaging you’re used to hearing. Good candidates will adapt and shift their message to speak to their voter’s new reality. I’ve been fascinated to hear Arizona Republican Senate candidate Blake Masters’ economic pitch. You can watch one of his rollout videos here, but here’s the nut:

In America, you ought to be able to raise a family on one, single income. We used to be able to do this. Something happened. Globalization, decades of inflation. Can’t really do it anymore. I think that’s a huge problem.

What makes this even more fascinating is that this used to be the Democrats’ message—add in some talk about unions and corporate creed and you’ll think you’ve been transported back to 1998. For those curious, the local Democratic Party attacked this Masters’ ad by saying it was “code for: women should not work” with the hashtag #Handmaiden.

The two-party realignment that was accelerated by Trump is real. The Democratic Party is now represented by a much higher percentage of wealthy, college-educated voters and far fewer blue collar, working-class ones. Republican candidates are no longer tied down by the three-legged stool of conservatism, which has led to a Darwinian explosion of new types of Republican candidates (though we have yet to see which ones will be most successful in breeding and passing along their genes, err, agendas). Add in a post-pandemic economic reality that politicians haven’t had to navigate since 1979 and it’s going to push both parties into new places.

The Virginia GOP nominated Glenn Youngkin via convention rather than primary.

Could that have made a difference in the outcome? Audrey reports.

Are Nominating Conventions the Virginia GOP’s New Secret Weapon?

Earlier this month, Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin became the first GOP candidate to win a statewide race in the commonwealth in 12 years.

Aside from Joe Biden’s sinking approval ratings, political strategists have largely attributed Youngkin’s victory to two main strategies: 1) his focus on local issues like K-12 education, public safety, and taxes, and 2) his ability to sidestep Democratic former Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s persistent effort to keep the spotlight on former President Donald Trump, who endorsed Youngkin but was never invited to join him on the campaign trail.

But one one part of the electoral equation has largely escaped national media attention. Before Youngkin beat McAuliffe in the general election, the GOP candidate first had to fend off his Republican challengers in the Virginia GOP’s nominating process.

Might Youngkin owe his victory to the Virginia GOP’s then-hotly contested decision to opt for a ranked-choice convention instead of a primary?

In ranked-choice elections, voters rank candidates by their first, second, third choices and so on. A candidate wins only by securing 50 percent of the vote. Until that threshold is met, the lowest vote-getter is eliminated and his or her voters are reallocated to the candidate they wrote as their second choice. Youngkin, a first-time candidate and former investment executive, led every round of the GOP convention, but didn’t win a simple majority until the sixth round, when he won 54.7 percent of the vote over second-highest vote getter Pete Snyder.

Mike Ginsberg, a State Central Committee representative from Virginia’s 11th District, said that the ranked-choice element of this year’s convention moderated this year’s GOP playing field by producing a ticket that appealed to a broad swath of Virginia’s Republican electorate. He said the idea to hold a convention was first proposed at a State Central Committee meeting in December, and it took four votes before the party made its final decision.

“The concern with the primary was that a candidate with very deep support in a very narrow slice of the electorate could still win a seven-way primary,” Ginsberg said. “That opens up the possibility of getting a candidate that’s very appealing to one wing of the party but simply isn’t palatable either to another wing of the party or to the independents and centrist Democrats that we thought we needed to get to win the election.”

It’s entirely possible that a primary would have allowed a more Trump-aligned candidate like Virginia state Sen. Amanda Chase—who was censured by her state Senate colleagues for calling those who stormed the Capitol “patriots”—to win the nomination by securing just 25 or 30 percent of the vote.

But the makeup of this year’s convention electorate made that outcome extremely unlikely, as only pre-registered delegates could vote for their desired candidate. Of the 53,000 Virginia Republicans who signed up ahead of the convention, 30,000 ended up voting in 39 voting locations across the commonwealth.

Convention advocates like Ginsberg argue that this pre-registration requirement produces an electorate that caters to the best interests of the party. “[Convention delegates] have a better feel because they’ve been sort marinated in the stuff a little more closely and have a better feel for what the party might need in any particular election,” Ginsberg said.

Unsurprisingly, not all candidates see conventions as the pathway forward for the Republican Party of Virginia. Shortly after the Virginia GOP announced its decision to opt for a convention, Chase threatened to run as an independent candidate “to bypass the political constituents and the Republican establishment elite who slow play the rules or even cheat grassroots candidates.”

Runner-up Pete Snyder was more ambivalent. “We obviously did have the success that we did with ranked-choice voting in the convention,” Snyder told The Dispatch. “This year if it had been a primary, I still think that we would have a great chance to win no matter what.”

But convention advocates say that without a convention, Youngkin wouldn’t have been able to escape the Trump-centrism that defines so many Republican nominating contests in today’s political environment. “I’ve heard a lot of people say, ‘When we got to the general election, we just let Glenn be Glenn,’ ” Ginsberg said. “Well, it was a lot easier to let Glenn be Glenn when he didn’t have six months as primary campaigning and attacks from people saying, ‘Oh he’s too Trump,’ or ‘Oh, he’s not Trump enough.’ ”

Next year’s Republican congressional primaries in Virginia are currently slated to take place June 21. We’ll be watching closely to see whether the state GOP opts to nominate its candidates via convention instead.

And Chris is here to discuss why the latest COVID variant might not be as much of a political problem for Democrats as Republicans have been claiming.

Partisan Gap on Vaccines Frees Dems to Push Shots, Not Restrictions

Contrary to the belief of some on the right, including the goofball caucus of the House GOP, top Democrats well and truly understand that the arrival of the Omicron variant of coronavirus and the lingering pandemic are massive political liabilities for their party.

It’s true that Democratic leaders are dealing with many in their own party who have formed unhealthy attachments to the expanded public health powers and social controls that sprang up with the response to COVID-19. But as President Biden’s remarks Monday on the latest variant of the virus made clear, those attachments are understood to be a liability. The Omicron strain, Biden said, would be met “not with shutdowns or with lockdowns, but with more widespread vaccinations, boosters, testing and more.” In a message likely aimed as much at his fellow Democrats as it was at nervous parents, investors, businesspeople, and workers, Biden said there was “not a cause for panic.”

There was lots of evidence in the state elections earlier this month that showed how public frustrations with pandemic restrictions have been hurting the blue team. And it’s a message that some Democrats have quickly absorbed: Shots, yes. Restrictions, no.

Many Republicans, who fear their own base voters, don’t want to appear to be getting on board with the vaccination drive. Some are even working to undermine the effort. For instance, a few GOP-led states are even offering payments to those workers who quit their jobs rather than getting vaccinated. Whether subsidizing vaccine refusal has significant effects on rates overall, it is at least a strong sign that the terrain may be shifting in Democrats’ favor.

Voters’ exhaustion with lockdowns, mask mandates, and school disruptions pits Democrats’ electoral needs against the party’s core interest groups, like teachers’ unions. The fight over vaccines, though, happens on Republican turf. While there are notable anti-vaccine zealots on the progressive left, this is now mostly a right-wing problem. The greater the degree to which Republicans slide into extremism and kookery or the kind of doubletalk we heard from Rep. Nancy Mace of South Carolina this week will be helpful for the party in power. In Virginia this month, most voters supported employer vaccine mandates. And polls nationally and in places like Texas also suggest strong support for vaccine requirements. If Dems can keep the focus on shots not restrictions, they can put Republicans in a pickle between their primary voters and the general electorate.

There are many reasons why Biden and his party failed to make this turn in the summer when the Delta variant presented itself. Americans’ frustration at seeing newly won resumptions of normal life snatched away was the beginning of Biden’s long slide into the doldrums. So why didn’t he and his party lean into vaccinations and away from restrictions? The situation was different and there were legitimate worries about the nature of the Delta strain. But there was something else, too. Back then, the gap between black Americans and white Americans on vaccinations was considerably higher than it is now. In July, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only about a third of black adults had been vaccinated compared to about half of white adults. While white vaccinations subsequently stalled, black vaccinations continued to rise at a higher rate. The gap is now just 7 points, 56 percent among whites, 49 percent among blacks.

Given the electoral significance of black voters to the Democratic coalition, pushing vaccines aggressively while there was still considerable resistance in the African American community would have come at a risk. But now, vaccine rejection is a much more neatly sorted partisan issue. In October, just 17 percent of unvaccinated Americans were self-identified Democrats compared to 60 percent who were Republicans. This should allow Biden and the rest of his party to focus blame on the Republicans who are working against vaccinations as the culprits. And with fewer of their own voters as part of the at-risk community, Democrats may feel bolder about forgoing restrictions.

There are lots of older, college-educated Republicans who are pro-vaccine, but the resistance is strongest among younger, less-educated members of the GOP. The more Democrats can tease out that conflict rather than the one over lockdowns and restrictions, the better it will be for their chances next year.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.