Programing note: If you’d like to vary up your media diet, check out the Dispatch Book Club. This month, we’re reading The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain by Annie Murphy Paul, which is a fascinating read on all the ways we learn and solve problems using gestures, social relationships, and even the physical spaces we work. I’m going to be interviewing her on a podcast just for Dispatch members that will be released at the end of the month. Come here to leave comments and engage with other Dispatch members along the way.

Remember, National Poll Numbers Don’t Matter

With the availability of so many national polling numbers—generic congressional ballot, presidential approval, issue polling—it can be easy to forget that none of them matter. If all of the support for Democrats is concentrated in high-population, far-left states like California and New York, then the national numbers will look deceptively positive. Lo and behold:

“Morning Consult Political Intelligence survey data gathered during the second quarter of 2022 shows voters in 44 states are more likely to disapprove than approve of Biden’s job performance, up from 40 states in the first quarter,” writes Eli Yokley, “Roughly 2 in 5 voters approve of his job performance in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.”

Stand By for Trump Announcement

“The former president is now eyeing a September announcement, according to two Trump advisers,” wrote Michael Scherer and Josh Dawsey in the Washington Post last week, “One confidant put the odds at ‘70-30 he announces before the midterms.’”

This is a no-brainer for Trump. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is the only potential threat right now—not even to winning the nomination, but even chipping away at the sense of inevitability. And DeSantis can’t announce until after he wins reelection in November. If Trump announces first, it changes the entire tenor of a DeSantis announcement in January. Then he is the one running against Trump. If DeSantis announces in January and six other candidates follow him, all while Trump flim-flams around without making up his mind until finally announcing in March, it looks like Trump is the one jumping in late.

But to be clear, Trump announcing in September is nearly comical in terms of the likely effect it will have on the midterms. Trump either didn’t care whether Republicans controlled the Senate under a Biden administration or actively wanted Republicans to lose those two seats in Georgia in 2021. Ditto the midterm elections if he announces in September.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think a Trump presidential campaign costs Republicans the House. There’s just too much baked in at this point. But the Senate is far from a foregone conclusion, and I can’t imagine Mitch McConnell wants Trump handing Democrats fodder for fundraising and television ads.

Out of State, Out of Mind

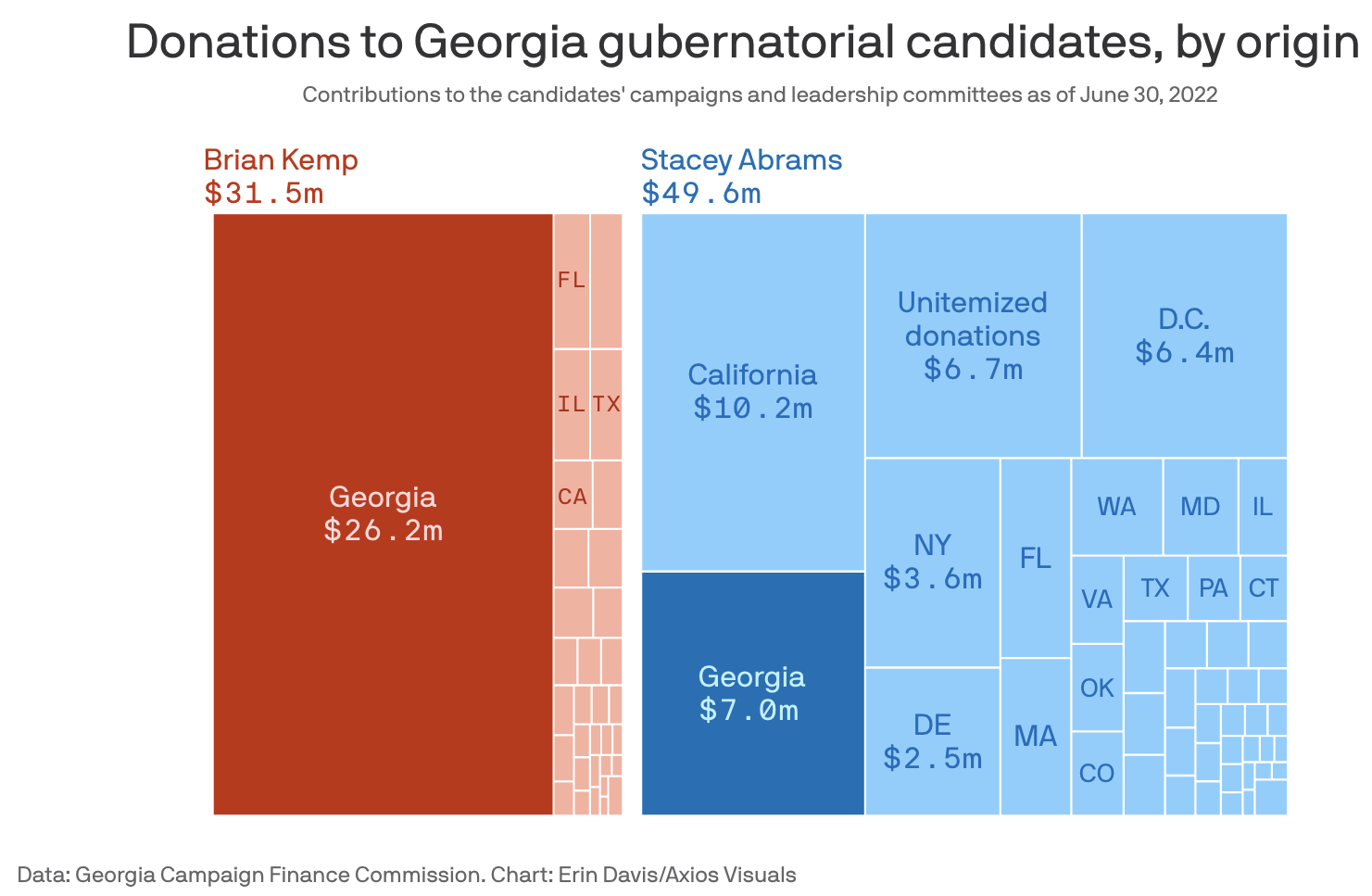

Less than 15 percent of Georgia Democratic gubernatorial nominee Stacey Abrams’ $50 million in campaign funds has come from Georgia donors. But does it matter?

On the one hand, California money spends just as well as Georgia money. And there’s a lot more low hanging fruit in California—both in terms of rich, liberal people who can write big checks but also people who have consistently given to liberal causes and are on a bunch of Democratic email lists that the Abrams’ campaign can easily rent. Georgia is a new purple state and the Democratic operatives haven’t been grooming donors—big or small—there for very long.

On the other hand, it’s more than just a messaging problem. But let’s be clear: It is a messaging problem. Especially for a candidate like Abrams, who was already going to be hit for not “representing Georgia values.” Then again, John McCain’s 2008 campaign team ran an attack ad comparing Barack Obama to Paris Hilton and Britney Spears—”he’s the biggest celebrity in the world … but is he ready to lead?”—and it bounced right off.

The bigger issue is that California donors don’t get to vote for Georgia’s governor. It takes time and money to raise money and, all things being equal, you’d like it to be a two-fer: a Georgia voter who donates $5 to Abrams is significantly more likely to vote for her because he is now literally invested in the campaign. Which is all to say, they’d rather be raising this money from Georgia voters. The fact that they aren’t almost certainly means they can’t. And that’s a bad sign.

The Party Realignment Continues

Ruy Teixeira, a longtime liberal political scientist at the left-wing think tank Center for American Progress announced he was decamping for the decidedly more conservative American Enterprise Institute. Normally, this news wouldn’t be relevant in a campaign newsletter, but Teixeira isn’t just any think tank wonk. He literally wrote the book—The Emerging Democratic Majority—on identity politics and predicted the rise of the Democratic coalition that elected Barack Obama in 2008. So why is he out?

Here’s some excerpts from an expertly written Politico piece from Michael Schaffer:

Politically, as a strategist, he thinks the Democrats need to win culturally moderate voters if they’re going to ever create the kind of coalition that can get their policies enacted. And personally, as an employee, he’s none too fond of the institutional dynamics that he says are driven by younger staff but embraced by higher-ups afraid of a public blow-up.

“I’d say they have been affected by the nature and inclination and preferences of their junior staff,” he says. “It’s just the case that at CAP, like almost any other left think tank you can think of, it’s become very hard to have a conversation about race and gender and trans issues, even crime and immigration. You know, ‘How should the left handle these?’ There’s a default assumption about how you’re supposed to talk about these things, even the language. There’s a real chilling effect on all of these organizations, and I think it’s had an effect on CAP as well.”

And now Teixeira is predicting a far less rosy future for Democrats.

“[Teixeira] predicted a governing majority based on the assumption that the Democrats could hold a healthy proportion of blue-collar white people, as happened in 2008,” writes Schaffer, “But Obama’s first win turned out to be a high-water mark, not a new epoch. Teixeira is in the camp that blames ‘cultural radicalism’ for this failure, saying the noise around things like pronouns and police defunding have made many blue-collar voters think of the party as a bunch of annoying recent liberal-arts graduates.”

Whereas Democrats are focused on catering to a progressive base, Teixeira sees the working class, non–college educated vote—a much, much larger share of the electorate than progressive slices that Democrats are wooing—slipping away from the party. And the data is on his side.

“Democrats now have a bigger advantage among white college graduates than they do with nonwhite voters,” wrote Axios‘ Josh Kraushaar based on data from the most recent New York Times/Siena College poll. This is an earthquake for a party that has been associated with blue-collar voters since the days of FDR. And in a political system with two parties that tend toward equilibrium, Republicans are realigning as well. “Republicans are becoming more working class and a little more multiracial; Democrats are becoming more elite and a little more white,” wrote Kraushaar.

In fact, CNN’s Harry Enten looked back at the racial gap on the generic ballot question from that same NYT/Sienna poll. “The average showed Democrats up by 30 points among voters of color and losing White voters by 14 points – a somewhat larger 44-point racial gap but still historically small,” wrote Enten. “In fact, it’s the smallest divide this century.”

So it’s not just the coalition of blue collar white voters that have been moving away from the Democratic Party since 2012. It’s the Hispanic vote that is starting to align itself—not along racial lines—but along the same educational, working-class lines as white voters.

“Democrats are statistically tied with Republicans among Hispanics on the generic congressional ballot,” wrote Kraushaar, noting that just four years ago, “Dems held a 47-point edge with Hispanics during the 2018 midterms.”

Teixeira agrees. This is from his recent newsletter:

In the 2020 election, Hispanic voters moved sharply away from the Democrats. Both Catalist and States of Change (forthcoming) data agree that it was around a 16 point pro-GOP margin shift (two party vote). States of Change data indicate this shift was heavily driven by Hispanic working class voters, whose support for the Democrats declined by 18 points. This pattern could be seen all over the country, not just in states like Florida (working class Hispanic support down 18 margin points) where they fell short but also in states they narrowly won (Arizona down 22 points; Nevada down 15 points).

The problem for Democrats is that the majority of American voters—and obviously, the majority of white and Hispanic voters—aren’t college educated and are in that blue collar category. As Teixeira notes, “Hispanic voters are overwhelmingly working class, around three-quarters in the States of Change data—higher than among blacks and much higher than among Asians.”

So as Democrats are realigning around college-educated voters, they are giving up on a much larger voting bloc in the process.

“Hispanic working class voters are overwhelmingly upwardly mobile, patriotic, culturally moderate to conservative citizens with practical and down to earth concerns focused on jobs, the economy, health care, effective schools and public safety,” writes Teixeira, “Democrats will either learn to hit that target or they will continue to lose ground with this vital group of voters—and in the process invalidate their increasingly tenuous claim to represent the American working class.”

Audrey has a story on the site today on Colorado’s Senate race:

How Joe O’Dea Survived Democratic Meddling

Last month’s Republican Senate primary in Colorado didn’t go as Democrats had hoped.

In the lead-up to the June 28 primary, Democratic Colorado, a left-leaning super PAC, released an ad calling far-right Republican Senate candidate and state Sen. Ron Hanks “one of the most conservative members in the statehouse” while boosting his conservative credentials on abortion, the border wall, and the 2020 election.

The hope was that Republican voters would take the bait and elect Hanks—a 2020 election-denying candidate with just $20,470 on hand as of early June—over moderate Republican candidate Joe O’Dea, giving Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet a much higher chance of sailing to reelection in November with his multimillion dollar war chest on hand.

But that didn’t pan out. Despite Democrats’ best efforts to tilt the election in favor of Hanks, O’Dea still won last month’s primary by 9 points. “People want somebody they can trust. They’re tired of all these games that the Democrats are playing,” O’Dea said in an interview earlier this month.

His victory means that at a time when inflation is surpassing 9 percent and voter confidence in President Joe Biden continues to wane, Bennet will now have to face what typically amounts to a Democratic incumbent’s worst nightmare in competitive midterm cycles—a moderate Republican.

“It’s not rocket science here,” O’Dea told The Dispatch while referencing rising crime and soaring consumer prices, among other kitchen table concerns that tip this year’s political environment in Republicans’ favor. “This is about what’s affecting Americans today.” He’s told voters that if elected, he plans to serve Colorado as a Republican version of Sen. Joe Manchin, the centrist Democrat from West Virginia.

O’Dea is still the underdog in this race: He’s running in a state that Biden won by 13 points in 2020, and has just $840,000 on hand (after raking in $2 million last fundraising quarter) compared to Bennet’s $8 million. But his victory paints a challenging picture for Bennet, who won his 2010 Senate race by 1.7 points and his 2016 race by 5.2 points—unremarkable margins of victory for what most election analysts consider to be a blue state.

And Biden’s 39 percent approval rating isn’t doing the Democratic incumbent any favors. “If things don’t get much better for Democrats, that’s a race that could be closer than expected,” said J. Miles Coleman, an elections analyst with Sabato’s Crystal Ball, adding that the Colorado Senate race still leans Democratic. “I can see it being a single-digit race.”

Coleman expects Bennet will undergo similar challenges this midterm cycle as Democratic Sen. Patty Murray in Washington, another vulnerable blue state incumbent who faces tough competition in GOP frontrunner Tiffany Smiley.

Inflation and Biden approval numbers aside, Bennet may also struggle to wield one of the only weapons Colorado Democrats have working in their favor ahead of the midterms—the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Keenly aware of the electoral dynamics of his state, O’Dea has adopted a far more nuanced stance on Roe’s reversal than most Republican candidates this cycle. “There’s a precedent there that it kind of kept things peaceful for a while, and so I wasn’t in favor of the overturning, just on the [precedent],” O’Dea said of the Supreme Court decision. “And now we’ve got a different law in every state. Not sure that’s good for America.”

The candidate said in an interview that he opposes legislative efforts to restrict abortion access “early on in the pregnancy or for rape and medical necessity.” But he made clear that he doesn’t support taxpayer-funded abortions or requiring religious institutions to perform abortion-related procedures.

As November draws near, both contenders will also face tough questions about who ought to be their parties’ respective presidential nominees in 2024.

On the Republican side looms former President Donald Trump, who is currently at the center of the ongoing January 6 investigation and who is expected to run for reelection.

“If it’s a question of him, or Hillary, or Kamala, of course I’m gonna vote for him. But we got a lot of good candidates in the party right now,” O’Dea said. He mentioned Republican Govs. Ron Desantis of Florida and Kristi Noem of South Dakota as potentially viable alternatives. “There’s a few people that could do an eight-year stint and I think that might be important. So I’d love to see how that all shakes out. That’s a ways down the road.”

Read the rest here.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.