Saving Democracy

So this isn’t great. “A New York Times/Siena College poll shows that 45 percent of Americans regard Trump as a ‘major’ threat to democracy, while just 28 percent say the same of the GOP,” writes Aaron Blake at the Washington Post. Okay. But it turns out “that 28 percent figure is actually smaller than the percentage who view the Democratic Party as a threat to democracy (33 percent).” Wait, what?

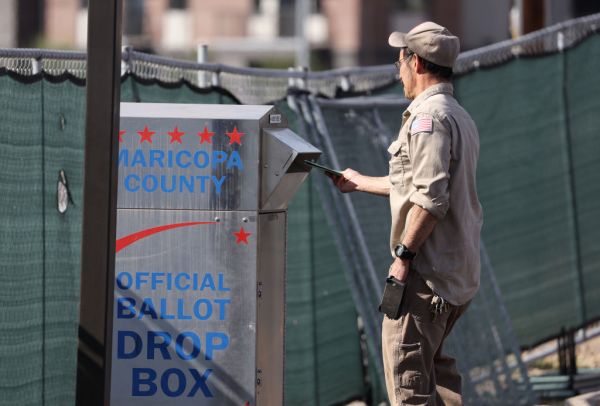

And independents are significantly more likely to view Democrats as a major threat than Republicans. Although more than 6 in 10 view each party as at least a minor threat, just 23 percent view the GOP as a major threat, while 31 percent say the same of Democrats. Independents are actually more likely to view voting by mail as a major threat to democracy (31 percent) than the GOP.

Maybe this could be written off for vagueness … what do each of these people mean by a “threat to democracy”? Then again, it’s a pretty ominous phrase regardless of the specific definition one may conjure.

But lest we think that poll was a one-off, here’s another startling nugget, this one from NBC: “Some 80% of Democrats and Republicans believe the political opposition poses a threat that, if not stopped, will destroy America as we know it.” That one feels pretty concrete to me.

Another poll asked “which of the following issues is most important in determining your vote.” The economy had the most takers at 40 percent. Threats to democracy came in second at 14 percent. Still, it’s worth remembering that “threats to democracy” isn’t the No. 2 issue. It’s the No. 1 issue for the second-most number of people. In that distinction lies a lot of difference, in my view.

Bottom line: We’re headed into an election in which large chunks of the country think both parties are major threats to our system of government. If you believe you’re on the side of democracy, you can justify nearly anything. Just ask John Wilkes Booth. And remember: The folks who attacked the Capitol on January 6 thought they were acting in defense of their country.

Democrats Are Seeing Red in 2024

Politico’s Burgess Everett did some great reporting and analysis on the 2024 Senate map. This year’s map, remember, is a pretty even match. Republicans are defending three open seats (Ohio, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina) and Wisconsin. Democrats are trying to hold onto Nevada, New Hampshire, Georgia and Arizona.

But 2024 isn’t nearly as balanced. Of 33 seats up, 23 are held by Democrats and 10 by Republicans. Just take a look at some of those states with seats held by Democrats: Montana, West Virginia, Ohio, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania. And that’s before we know which Democratic incumbents will retire. As we’ve seen this year, open seats make for tight races. And on the Republican side, there’s not much vulnerability—Texas? Florida? Indiana may be the best bet for Democrats looking for a pickup because Republican Sen. Mike Braun is retiring to run for governor. But Indiana isn’t exactly a purple state these days and it’ll be a presidential cycle with high partisan turnout.

Which is all to say: Unless Democrats pick up two or more seats next week, Republicans could go into 2024 as heavy favorites for Senate and House control. And if Republicans sweep Arizona, Nevada, and Georgia this time around, they could even be a long shot for a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate come 2024. Then again, we’ve heard that before (cough, cough, 2020 when Republicans lost two very winnable seats in Georgia, and 2012 when Republicans lost Indiana, North Dakota, Maine, and Missouri).

Where Some Senate Candidates Are—and Aren’t—Chasing Gubernatorial Candidates’ Coattails

Republican Senate candidate Dr. Mehmet Oz struck out in the gubernatorial coattails department this midterm cycle. Locked in an already tight Senate battle against Democrat John Fetterman in Pennsylvania, Oz has spent the entire general election race keeping his distance from his own party’s gubernatorial nominee—far-right 2020 election-denying state Sen. Doug Mastriano.

Mastriano trails his Democratic challenger Josh Shapiro—Pennsylvania’s attorney general—by roughly 7 points in RealClearPolitics’ polling average, largely because of his refusal to pivot to a general election strategy that appeals to moderates, independents, and suburbanites (i.e. the exact voters Oz needs to pull off a statewide victory). And even as Oz stands to benefit from the race’s increased focus on crime and lingering questions surrounding Fetterman’s health post-stroke, Republicans are concerned that Mastriano’s unpopularity could bleed into the toss-up Senate race.

It’s no wonder then that Oz has declined to campaign alongside Mastriano. “It’s rare to see as weak a nominee as Mastriano,” said Jessica Taylor, the Cook Political Report’s Senate and governors editor. “Josh Shapiro’s been running an excellent campaign and Doug Mastriano has barely been running, so Mastriano is certainly not helping Oz.”

On the gubernatorial coattails question, Oz likely envies his fellow Republican Senate hopefuls in Ohio, Arizona, Nevada, and Georgia, where strong GOP gubernatorial incumbents (and even first-time candidates!) could help pull down-ballot candidates across the finish line.

(Note: we use the phrase “down-ballot” a lot and it literally refers to the order that races appear on a voter’s ballot … but that’s not the same in every state. In Texas, federal races come first. In New Hampshire, governor will come first. In common parlance, then, down ballot means the races in descending order from president, governor, Senate, Congress, to lieutenant governor and attorney general, etc.)

In Ohio, for instance, Republican Senate nominee J.D. Vance stands to benefit from Republican Gov. Mike DeWine’s coattails in his toss-up bid against Democratic Senate challenger Tim Ryan. The same goes for embattled Republican Senate candidate Blake Masters in Arizona, who trailed Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly for most of the general election but could eke out a win with the help of strong Republican political winds and first-time GOP gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake’s coattails.

“Lake and Masters are seen to be very much running as a ticket,” said J. Miles Coleman, an elections analyst at Sabato’s Crystal Ball. “Mark Kelly and [Democratic gubernatorial nominee] Katie Hobbs don’t have as much of a sense of unity.”

A similar dynamic is playing out in Georgia, where vulnerable Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock is locked into a less-than-ideal party ticket with weak gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. If election analysts at Sabato’s Crystal Ball are right and Abrams loses her rematch against Republican Gov. Brian Kemp and neither Senate candidate secures 50 percent of the vote, expect Walker to continue chasing Kemp’s coattails into the runoff.

What About Ticket Splitting?

Ticket splitting is becoming rarer and rarer. From Sabato’s Crystal Ball: “2016 marked the first time in the popular vote era where every state that had a Senate contest voted exactly as it did for president. The last election was not much different on that front: only Maine, a state well-known for its idiosyncrasies, split its ticket.”

Still, there are a few states this cycle where voters might elect a Democratic governor and Republican U.S. senator (and vice versa.) Take New Hampshire, where popular Republican Gov. Chris Sununu is running on the same ballot as GOP Senate nominee Don Bolduc, a former election-denier running against Democratic Sen. Maggie Hassan. (It’s an incredibly awkward Republican ticket. Ahead of New Hampshire’s mid-September Senate primary, Sununu endorsed Bolduc’s Republican challenger and called Bolduc “kind of a conspiracy theorist-type candidate.” That’s after Bolduc called Sununu a “communist Chinese sympathizer.”)

Only after Election Day will we be able to see whether ticket splitting will make much of a difference in a handful of other battleground states, namely Nevada, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia, and Ohio. “There’s a decent number of these educated suburban voters who like the concept of balance: ‘Oh, well I’m gonna vote for one party for the Senate the other party for governor,’ ” Coleman told The Dispatch. “That can be decisive in a close race, but that bloc of voters isn’t a majority of the electorate.”

Still, just because a state elects candidates from both parties doesn’t necessarily mean there were a lot of voters who pulled the lever for both—check the numbers of voters in each race to make sure there wasn’t substantial dropoff.

Right-Wing Media Shifts in 2022

Several months ago, Axios made this graphic to capture just how profoundly the Republican Party has changed—and how operatives think about winning GOP primaries these days. “Fourteen of the Republican Party’s top consultants and operatives across the country spoke in detail with Axios about how profoundly primary races have changed since 2014,” according to Axios reporters Jonathan Swan and Lachlan Markay, “the last pre-Donald Trump midterm election and the last midterms in which a Democrat occupied the White House.”

It may also surprise you to see where the readership is. In the chart below, you’ll notice that Fox News isn’t just No. 1 (and again, this is about website views—not television). Fox has 10 times the visitors that No. 2 has. And I’ll bet a lot of you have never heard of No. 2: Epoch Times, which is up 57 percent in website traffic over last year.

When political consultants take on a candidate in a contested primary, it’s all about creating a narrative. For a GOP primary candidate, it’s about picking the right fights and getting the right people to notice your fights. It’s why you send your GOP candidate on The View. It’s not because you think he’s going to have a nuanced discussion over trade policy that will really make viewers consider the profound implications of Chinese carbon adjustments. It’s because there’s likely to be a verbal brawl and you want to send out fundraising clips on social media of your guy “taking on” the left-wing women of The View as a stand-in for Hillary Clinton or Kamala Harris.

As I’ve said before, in the era of max-out donors writing $2,000+ checks, conservative organizations had a lot of power. Highlighting a candidate to their donor network was as good as money in the door. But in the era where a campaign can bring in way more money through small-dollar donations while dedicating far less of the candidate’s time to courting donors, an endorsement from those same organizations is as much a liability as anything else—proof that a candidate is in the pocket of high-dollar donors.

Just take a look at this profile of the most successful fundraiser in the Arizona state legislature, Wendy Rogers:

Rogers’s trajectory shows the political and financial incentives of going to extremes. After losing her earliest races as a mainstream Republican, she moved further and further right until she beat an incumbent by campaigning as the more conservative choice. She raised nearly $2.5 million in 2021, outraising even statewide candidates for governor, attorney general and secretary of state, according to campaign finance records. Nearly $2 million of that money came from small donations from outside Arizona as she traveled the U.S. calling for the 2020 election to be overturned and demanding audits of the vote without credible evidence of fraud.

And on the media side, it’s almost more stark. Audience size is important. But as you’ll see comparing the Axios graphic to the audience size graphic, size isn’t everything. Audience tenacity is king now. Highly intellectual debates about which candidate hews most closely to William F. Buckley’s original vision of Burkean conservatism isn’t going to inspire anyone to send in $20 online. The fall of Drudge could be the basis for a whole longform essay. “The Drudge Report used to be able to shape multiple conservative news cycles with one headline alone,” as Swan and Lachlan described it, “These days, after a long fight with Trump, it’s viewed skeptically if not unfavorably by many Republicans.”

But there’s one thing I don’t think the Axios graphic captured. The media landscape overall—not just on the right—has fractured. Pre-2014, there weren’t a lot of options on the right. National Review, The Weekly Standard, the Wall Street Journal, and Fox News had the majority of the known conservative voting audience AND they had the majority of known conservative writers from various branches of the movement. And getting one of those headlines on Drudge was golden.

Fast forward and there are a zillion more places to get news, but the range of voices you can read at a single outlet have been narrowed as well. So the Axios graphic certainly covers who these political consultants think has the power to move primary voters, but it’s a chicken and egg issue. Breitbart hasn’t replaced National Review circa 2005, but that’s because the model for a place like National Review no longer exists. Instead, Breitbart speaks both for and to a plurality of GOP primary voters. To put it another way: They’re on top in terms of influencing primaries because primary voters who agree with them are on top.

Worth Your Time

Here’s a great read by Kathy Gilsinan in Politico Magazine. It starts with an interview with the owner of “a bar and restaurant in the politically swingiest county in one of the politically swingiest states in the country, and it’s one that tends to pick winners.” Gilsinan reports from Sauk County, Wisconsin:

“Everyone descends because they’re hoping somebody is going to crack the code,” she said, but “I don’t think the code is crackable. You know, we’ve got 50,000 people in Sauk County, and in 2016, Trump won by 109 votes.” In 2020, he lost the county by 615. These are not margins that lend themselves to sweeping conclusions. Still, Walker ran through the spiel about life in her purple county, how if there are six people sitting at the bar, three voted for Trump and three for Biden in 2020, and she knows all of them and where they work and what they drink and what they drive.

Just imagine sitting through $344 million worth of ubiquitous and increasingly negative political advertising in the last few months and you can understand the Wisconsin swing voter who told her, “It feels like we’re being punished for something.”

One Last Thing

Saturday Night Live used to have some of the best political content—Admiral Stockdale rolling out of the car, Reagan and the Girl Scouts, Al Gore’s lockbox. The show feels like it’s moved to the left since those days, unable to make fun of each side’s foibles. So this bit was a nice throwback:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.