With only four remaining workdays in the House and three in the Senate before a five-week recess, the deadline to fund the government for the next fiscal year is much closer than it appears. The Republican-controlled House and Democratic-controlled Senate have until September 30 to settle on both topline funding levels and policy amendments—and the gulf between the two chambers has only grown this summer.

One paper it might seem as if Congress is striding toward both chambers’ stated goal of passing 12 annual appropriations bills through regular order for the first time since 1996: So far, the House Appropriations Committee has approved 10 of the 12 bills its subcommittees have drafted, and their counterparts in the Senate have approved eight.

But none of those bills are expected to become law. House appropriators have come up with bills that fall well short of the spending caps laid out in the debt ceiling deal from earlier this year, while the Senate Appropriations Committee wants to go above the caps, at least when it comes to defense.

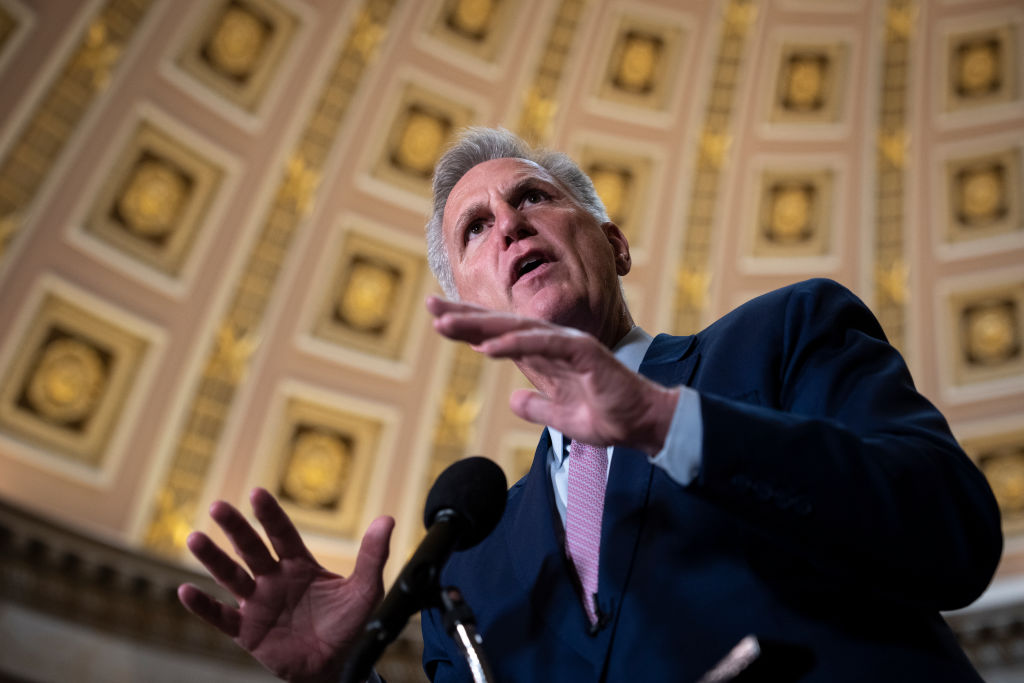

As it was with debt ceiling in May, so it is with appropriations: While most House Republicans are prepared to follow Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s lead through negotiations with the Senate and the White House, some in the conference think the party leadership’s preferred bills are insufficiently conservative—for example, by relying on “clawbacks” or recissions of unspent funding from this current fiscal year rather than actually reducing next year’s spending. Earlier this month, a group of 21 Republicans—led by Freedom Caucus Chairman Scott Perry—wrote McCarthy a letter vowing to withhold their votes from any appropriations bills that reach the topline spending levels of the debt ceiling agreement.

The group also urged McCarthy to “hold floor consideration of any appropriations measure until all 12 bills have been reported out by the Appropriations Committee,” a request reiterated at a Freedom Caucus press conference Tuesday morning. That request hasn’t been granted yet, and the two outstanding bills deal with touchy subjects such as FBI funding and gender-transition surgeries, among other things.

But in an initial test of party unity, the full House is expected to vote later this week on two of the 10 bills that have come out of the committee: one on military construction and veterans affairs, and another on agriculture. The Rules Committee is scheduled to meet this afternoon to decide how to bring the military construction measure to the floor, which will shape the timeline for the rest of the week.

Those votes are meant to “put a good taste in the Republican conference’s mouth as far as the shape of this year’s spending bills” one GOP legislative director says. That would be similar to the bill Republicans passed to demonstrate unity within the conference going into the debt ceiling debate and draw the White House to the negotiating table. GOP leaders may face some potential pitfalls—moderate New York Rep. Marc Molinaro, for instance, has pledged to vote against an amendment that would ban mail distribution of the abortion pill, which could doom the agriculture bill if enough Republicans joined him. But the White House’s explicit veto threat to both bills on Monday may help whip Republican votes.

Regardless of whether the week goes according to McCarthy’s plan, options for funding the government starting October 1 are narrowing. Setting aside the ideal of passing 12 separately negotiated bills—which would be both procedurally and politically difficult—there are few other options: an omnibus spending package (or a set of smaller “minibuses”), a continuing resolution temporarily keeping funding at current levels, or a government shutdown.

Eventually, McCarthy may not need Freedom Caucus votes to pass a continuing resolution or an omnibus—by that point, many of the same Democrats who voted for the Fiscal Responsibility Act to end the debt ceiling showdown might be on board. But he does need to make sure none of the GOP holdouts trigger a motion to vacate the chair, putting his job in jeopardy.

Under the House Rules adopted in January, just one member can force a full House vote on whether to remove McCarthy as speaker. A motion to vacate the chair contributed to then-Speaker John Boehner’s decision to retire in 2015—but that motion wasn’t “privileged” as it would be in McCarthy’s case, potentially reverting the floor back to the chaos of the first week of January. Hence the need to humor the right flank’s shutdown threats.

Another Republican staffer tells The Dispatch that a majority of House Republicans would likely support an appropriations deal at the levels laid out in the debt ceiling deal, and that many are frustrated by the precariousness of McCarthy’s position.

“There’s a bipartisan, bicameral deal that can be reached here, but McCarthy can’t do that without risking the support of his most conservative members,” he said.

But the Freedom Caucus threatened McCarthy with a motion to vacate over the debt limit agreement months ago, and he still has his job.

“It’s quite possible that it just ends up being overblown and they strike an eleventh-hour deal,” says Ben Ritz, a fiscal policy analyst at the center-left Progressive Policy Institute. “We just kinda have to see.”

On the Floor

In addition to the two appropriations bills, the House may vote on a pair of joint congressional resolutions of disapproval related to new rules promulgated by the Fish and Wildlife Service within the Department of Interior.

The Senate will be considering its own version of the National Defense Authorization Act.

Key Hearings

- The House Judiciary Committee will question Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas in a hearing on Wednesday.

- The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources will hold a hearing on permitting reform on Wednesday.

- The House Foreign Affairs Committee’s Subcommittee on Oversight and Accountability will hold a hearing on Thursday covering the Biden administration’s planning for withdrawing U.S. troops from Afghanistan in 2021.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.