Good morning.

The Capitol is approaching something near normalcy, as many members of Congress have been vaccinated and more of their staff are returning to in-person work. More reporters are showing up to votes to ask members questions. And several restaurants in the House office buildings reopened this week for the first time since shutting down for the pandemic. People are still wearing masks, and some hearings are still virtual. But there is increasing pressure, especially among Republicans, for the House to move to some of its pre-pandemic operations—with quicker votes and even tours for constituents. It’s not clear when Democratic leaders will feel comfortable moving forward with some of those steps. They have raised concerns about some members not having received a coronavirus vaccine yet, as well as ongoing community spread around the country. And the CDC guidelines for those who have been fully vaccinated still recommend wearing masks in public places, as well as social distancing. Still, the building was busier than usual this week, as lawmakers returned from a lengthy recess.

Infrastructure Week

In the Senate, a group of 10 Republicans and 10 Democrats began to discuss a potential bipartisan infrastructure package. (Senate Democrats need at least 10 Republicans to vote alongside them if they are to pass anything by regular order, rather than through the budget reconciliation process.) Senators said they are considering a measure in the range of $800 billion—although that price tag is very much still in the air—that would focus on roads, broadband, water systems, airports, and other forms of traditional infrastructure. Sen. Mitt Romney told reporters the talks are “still in the early stages.”

There’s a lot that could threaten the discussions: Democrats and Republicans are especially at odds over how to pay for the investments. Democrats have called for an increase in the corporate tax rate as a financing measure, whereas Romney said he would prefer user fees.

“My own view is that the pay-for ought to come from the people who are using it. So if it’s an airport, the people who are flying. If it’s a port, the people who are shipping into the port,” Romney said during a vote series Wednesday. “If it’s a rail system, people who are using the rails. If it’s highways, it ought to be a gas [tax] if it’s a gasoline-powered vehicle. If it’s an electric vehicle, some kind of mileage associated with that electric vehicle that would be similar to or the same as the gasoline tax.”

The prospect of a slimmer, bipartisan infrastructure plan does not rule out the possibility of a much more expansive reconciliation bill packed with Democratic priorities afterward. That dynamic—balancing Biden’s desire to work with Republicans with his sweeping ambitions for the legislation—is what will ultimately determine Democrats’ approach. There was a similar moment of potential bipartisanship before Democrats rejected Republicans’ slimmer coronavirus aid proposal and moved ahead with their own nearly $2 trillion bill earlier this year. Some progressives have again expressed little patience for a bipartisan bill this time, saying the infrastructure components should just be rolled into the larger package, including universal pre-kindergarten, free community college, and climate change provisions.

But some Democrats see value in a two-pronged approach. A bipartisan measure for some of the investments Biden is seeking would empower Democrats to avoid some of the constrictions of the budget reconciliation process, while also bolstering Biden’s image as a dealmaker.

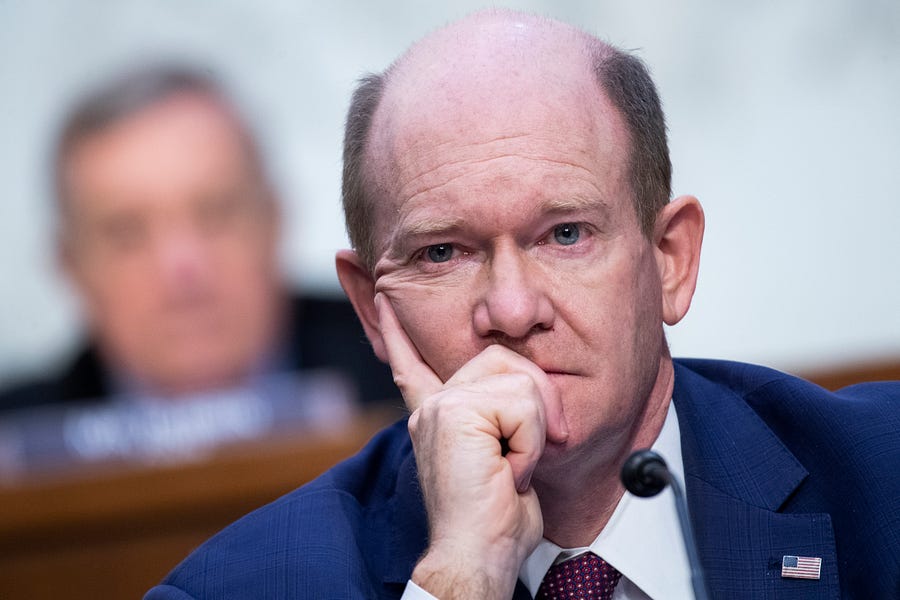

“Let’s just say, notionally: The president and our caucus, we are trying to get $2 trillion worth of infrastructure and job investments moving ahead,” Delaware Democrat Sen. Chris Coons told reporters Thursday. “Why wouldn’t you do $800 billion of it in a bipartisan way and do the other $1.2 trillion Dems-only through reconciliation? Why wouldn’t you do that?”

That raises the question: Why would Republicans negotiate with Democrats, knowing the entire time that Democrats may just go on to pass their priorities without them through reconciliation afterward? Some, like Louisiana Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy, have said they would only consider an infrastructure plan with the “implicit understanding that this will not lead to a second bill.”

But West Virginia Republican Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, who is also involved in the conversations, has indicated she would not mind if Democrats proceed on that path. In an interview with CNBC earlier this week, she said Republicans and Democrats should first pass items that have bipartisan agreement.

“Let’s pull that together, and if there are other things they want to do—they being the Democrats and the president—want to do in a more dramatic fashion that can’t attract at least 10 Republicans, that’s, I think, their reconciliation vehicle,” she said. “And that’s what I would use to raise your taxes if that’s what they want to do, or to incorporate some more of the things that I don’t happen to agree with, some more of the Green New Deal issues or the social infrastructure issues.”

Talks between the group of 20 senators will continue next week.

Congress Considers Afghanistan’s Future

Lawmakers were divided this week over President Joe Biden’s plan to withdraw remaining American troops from Afghanistan by September 11.

Most Democrats and a smattering of Republicans praised the move, saying it is time to bring military personnel home from a war that has lasted nearly two decades, costing more than 2,400 American lives and $2 trillion. But the bulk of Hill Republicans and a few Democrats questioned the wisdom of leaving Afghanistan this year, as the Afghan government has struggled to hold the insurgent Taliban at bay.

Biden is the third president in a row to publicly prioritize ending the war. Former President Donald Trump planned to exit the country by May 1 of this year had he been reelected. Biden told reporters this week that the decision to end American involvement in Afghanistan was not a hard decision. “It was absolutely clear,” he said.

But the drawdown of coalition forces could present an opening for the extremist Taliban to take more territory—and potentially return to power in the country as a whole. Afghan civilians, especially women, are facing an even more uncertain future as the United States prepares to leave. Some fear that militant violence and civil war will escalate, and they worry more progressive ways of life will be stamped out if the Taliban makes gains. (The New York Times has good reporting from Afghanistan about these concerns here.)

“Any withdrawal of forces that is not based on conditions on the ground puts American security at risk,” Rep. Liz Cheney, a Republican national security hawk, told reporters Wednesday. She argued that the pullback will “provide an opportunity for terrorists to be able to establish safe havens again.”

“It also puts the women of Afghanistan at risk,” Cheney added. “It puts the women of Afghanistan into the position they were in potentially 20 years ago where their lives are not valued, where they have no freedom.”

Members of Congress who supported Biden’s move recognized it as a difficult situation, but they questioned what the end game would be if American forces were to remain in the country indefinitely.

“I’ve listened to military leaders tell me for 15 years that we just need to stay for one more year,” Connecticut Sen. Chris Murphy—who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee that focuses on the Middle East and counterterrorism—told The Dispatch this week. “At some point, you need to accept the facts on the ground. And the facts on the ground tell us that the U.S. presence there is not leading to the defeat of the Taliban, nor the Afghan government being able to govern effectively. If we were to stay for another year, I think it’d be an acceptance that our presence in the country is permanent. And there’s also too many much more pressing threats to the United States that demand our attention. So the president’s decision was the right one.”

The U.S. intelligence community raised alarms at the prospect of a coalition withdrawal earlier this month. “The Taliban is likely to make gains on the battlefield, and the Afghan Government will struggle to hold the Taliban at bay if the coalition withdraws support,” the annual Worldwide Threat Assessment concluded. “Kabul continues to face setbacks on the battlefield, and the Taliban is confident it can achieve military victory.”

Asked about the recent assessment, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren told The Dispatch that Biden made the right call, and it “should have been made a long, long time ago.”

“I want to hear their answer: Do they expect the United States to stay in the same place and continue waging war for the next 20 years? The next 50 years? The next hundred years?” she responded. “It’s time to withdraw.”

And Maryland Democrat Sen. Ben Cardin said he has “a lot of confidence in President Biden understanding the landscape there.”

“This has been successive administrations that have left us in a very difficult posture,” he said. Cardin added that he expects upcoming congressional hearings on the move as well as classified briefings from the Biden administration.

Since Biden’s announcement, senators have had conversations among themselves about how to stand alongside the Afghans who helped the war effort and others who are most threatened by a potential Taliban rise to power.

Delaware Sen. Chris Coons, a close ally of President Biden, said Congress needs to provide “robust funding for translators, for those who worked with us and supported us, and make sure that we are doing right by the Afghans who took real risks to serve alongside us over the last 20 years.”

Coons said senators should expand the Special Immigrant Program, which has for years allowed Afghan nationals who worked as translators with the American military and others who worked for or on behalf of the U.S. government or the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan to come to the United States as lawful permanent residents.

Intelligence capabilities will also take center stage: Central Intelligence Agency Director William Burns told the Senate intelligence committee this week that his agency’s ability to gather information about emerging terror threats from Afghanistan will diminish in the absence of American troops. Still, the CIA will “retain a suite of capabilities,” he said.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken emphasized that the American relationship with the democratic Afghan government is not ending, even as the coalition coordinates its exit from the country. He made a visit to Kabul Thursday morning, telling Afghan President Ashraf Ghani he wanted to demonstrate “the ongoing commitment of the United States to the Islamic Republic and the people of Afghanistan.”

“The partnership is changing, but the partnership itself is enduring,” Blinken said.

Gallagher on the Remnant

Wisconsin Rep. Mike Gallagher sat down with Jonah over some whiskey the other day for the latest episode of The Remnant podcast. It’s about two hours long and a bit of a wild ride. I’ve included some of the more … serious highlights (edited lightly for clarity) below. (You can listen to the full thing here.)

-

Gallagher said he doesn’t have plans to primary Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson. “That is never going to happen,” he told Jonah. “It is both my fondness for my fellow Badger State Republican, as well as I just don’t think anyone is interested in sort of the nerdy, half-baked ideas brand of politics that I bring at this present moment.” Gallagher added that Wisconsin has a late primary process, and he thinks “the best chance of us retaining the seat is for Ron Johnson to run again, just so we avoid a primary process, which is going to get bloody.” He also indicated he isn’t particularly enthusiastic about the prospect of diving into the chaos of today’s high-profile GOP primaries: “It seems like so far, all of these statewide primaries are becoming a weird exercise in just trying to get Trump’s endorsement,” Gallagher said.

-

Gallagher also made clear he’s not a fan of Democrats’ sweeping infrastructure proposal. “We could buy Greenland for that money,” he said. “You could build a bunch of semiconductor fabrication sites. You could fix our ship building problem. You could pour a bunch of money into AI, strategic research, and you still have enough money left over to vaccinate the rest of the world and sort of win vaccine diplomacy going forward.”

-

Asked if he actually likes being in Congress, Gallagher said he loves two things about it: Learning more about his district and the serious committee work. “I get to go around my district and just meet with a bunch of people and tour businesses and this and that. It sounds cheesy, but you get to understand your district, the place you grew up in, better than you ever would have before,” he said. “And then I love the committee work—like on the Armed Services committee, I’m doing some cool stuff. I’m co-chairing a supply chain vulnerability task force with Elissa Slotkin from Michigan. That stuff’s awesome. And I love the intersection of defense tech, U.S.-China competition.” But he also pointed to some downsides: “I hate fundraising,” he said. “The current political environment, I’m just like not suited to at all. I am not good at social media. It’s not my thing. So that stuff sucks. And the feeling that there’s no incentive for doing good work is not a good feeling.”

-

Asked if America has gotten better or worse in the past five years, Gallagher said it has “unquestionably” gotten worse, “because we’ve gone to war with ourselves.” “I spend a lot of time thinking about, as I said before, U.S.-China competition, what I would call a new Cold War,” he said. “What strikes me as the difference between the old Cold War—as someone who wrote his dissertation on the old Cold War—and the new is that there seems to be no consensus that we’re the good guys and that we deserve to win. And that’s a huge problem.”

-

The external threat posed by China is not having that galvanizing, unifying impact of ‘Hey America: We need to get our ish together right now,’” Gallagher added. “And we don’t need to agree on everything. We don’t just sing kumbaya and hold hands. But there are a few things we need to do. We need to have the best K-14 system in the entire world. We need people to work and bust their butt. We need all the exciting next generation high-tech manufacturing firms to be located in America. I don’t know. We don’t seem to be having that conversation as a country.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.