Right after winning the gavel this week, newly installed House Speaker Mike Johnson made the same promises his recent predecessors made about how he’ll perform his duties. “The job of the speaker of the House is to serve the whole body, and I will,” he said in remarks after his victory on Wednesday. “I’ve made a commitment to my colleagues here that this speaker’s office is going to be known for decentralizing the power here. My office is going to be known for members being more involved and having more influence in our processes, in all the major decisions that are made here, for predictable processes, and regular order. We owe that to the people.”

The speech was likely music to some rank-and-file members’ ears—but a song they’ve heard before, too. Several recent speakers made similar pledges upon ascending to the role, but they ultimately failed to follow through. Legislating is messy—particularly in this increasingly polarized Congress—and speaker after speaker has proven unable to resist wielding the immense power the office has accumulated in recent decades to pass bills faster and with more of their conferences’ backing.

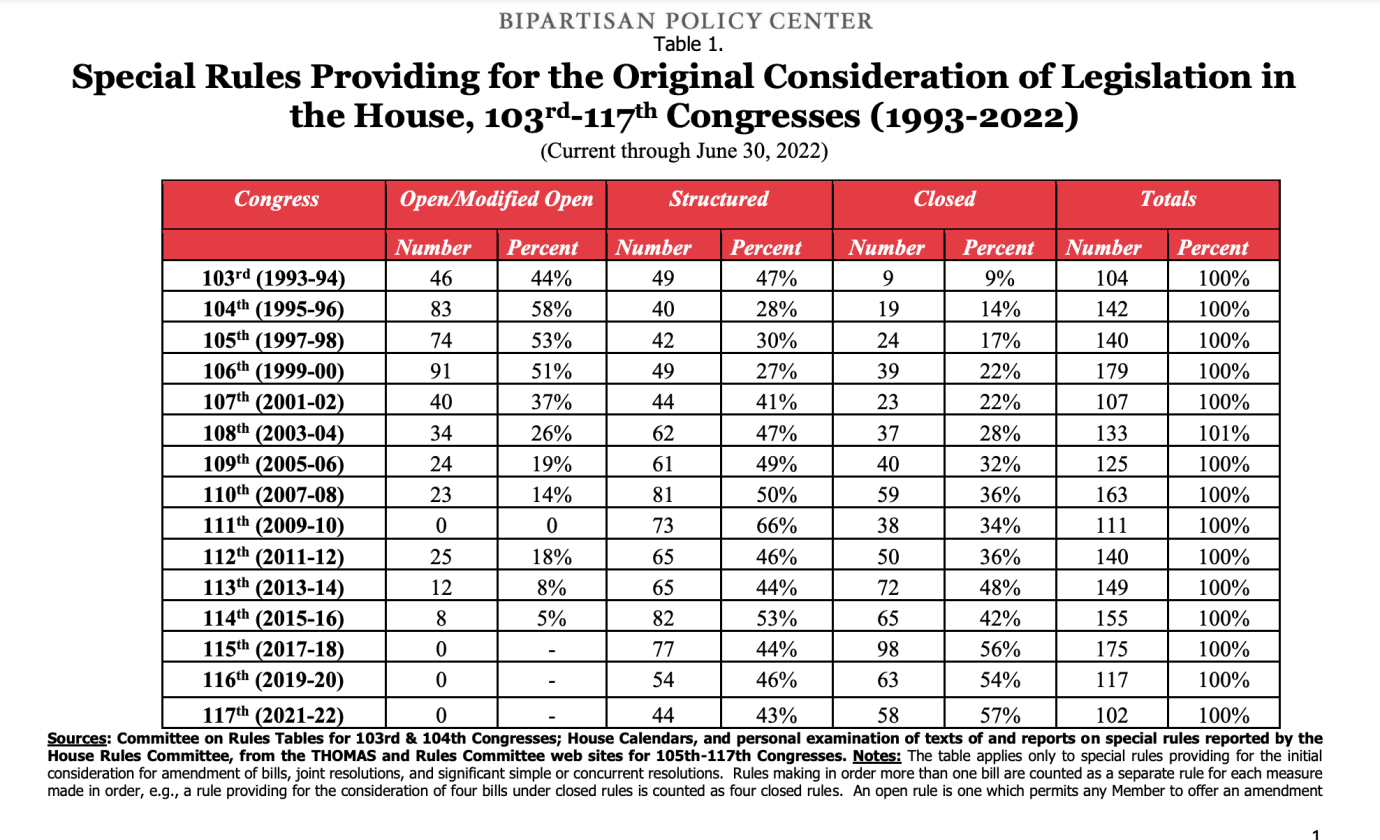

Former Speaker Paul Ryan, for example, broke records in 2017 and 2018 for having the most closed rules in a session of Congress, blocking members from being able to offer amendments—after pledging a “more open, more inclusive, more deliberative, more participatory” legislative process when he became speaker in 2015.

“We’re not going to bottle up the process so much and predetermine the outcome of everything around here,” Ryan told reporters shortly after becoming speaker. As you can see in this data compiled by the Bipartisan Policy Center, former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s tenure largely saw a continuation of that top-down approach. (You’ll notice there were no open or “modified open” rules in three successive Congresses, meaning there were no opportunities for members to offer amendments without first getting them approved for consideration by the Rules panel).

This phenomenon is not entirely the speaker’s fault. Vulnerable lawmakers generally expect speakers to protect them from politically difficult votes whenever possible. And conservative Republicans who like to talk about the need for member-driven regular order often end up demanding specific policy outcomes from their leaders—the opposite of regular order—with implicit or explicit threats attached. As we reminded you in this newsletter earlier this year, when Ryan allowed freewheeling amendments on spending bills in 2016, Democrats advanced LGBTQ protections in one of them, with support from more than 40 Republicans. That led conservatives to tank the overall water and energy spending bill that had been amended. GOP leaders quickly pivoted to a more closed process, where outcomes would be more predictable and Republicans would be able to approve their own legislation.

Could Johnson’s tenure actually bring change in how power is structured in the House? Maybe, but some lawmakers aren’t very optimistic. Two House Republicans told The Dispatch this week they think an internal conversation about what is expected of the speaker is needed after former Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s ouster.

“What we need to talk more about is what is the role of the speaker versus the majority leader versus the whip versus the conference chair,” Rep. John Duarte of California said the night before Johnson was elected. “The speaker really isn’t the person who’s necessarily charged with driving the majority’s political agenda. That’s the majority leader.”

Duarte is right that historically, the speaker’s job looked a lot different: Speakers relied on committee chairs to craft bills and had less control over what legislation looked like when it made it to the floor. But today, speakers functionally serve as campaign fundraising heavyweights, shepherd their party’s priorities through the chamber, mediate between different ideological factions, negotiate with the White House and the Senate, and spend a lot of time on the campaign trail attempting to boost incumbents.

In a 2018 piece for The Atlantic, Rep. Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin lamented power accumulation among congressional leadership and noted that rank-and-file members often quietly like this arrangement more “because it prevents them from having to cast tough votes.”

Five years later, he still has those concerns. “This is not going to happen any time soon,” Gallagher told The Dispatch this week, “but I would be intrigued to go back to a model where the speaker runs and defends the institution and isn’t the fundraiser-in-chief of the House.”

What would that look like? What would Johnson have to do to actually decentralize power in the House? The Dispatch spoke with Josh Huder, a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Government Affairs Institute who specializes in Congress, separation of powers, and the legislative process, about those questions and more. The transcript of our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The Dispatch: When did the role of the speaker really shift into what it is now?

Josh Huder: For most of the 20th century, members of Congress were sort of left to their own devices when it came to reelection. Parties were not national in character. They were state and they were local. So a member of Congress’ return to Congress, like winning their primary, was largely a function of state and local politics. It was not this kind of national-oriented, “You must toe the party line” thing. That’s really something that happened in the 1980s, 1990s. And you can start to see institutionally, the speaker became much more powerful in the mid-1970s, but they took on this more intense political role, for lack of a better term, in the ‘80s and ‘90s. That’s really when they started to become fundraiser-in-chief, party leader-in-chief within the House of Representatives. Before that, members of Congress did not rely on the speaker for their reelection. In fact, it was often best that the speaker did not talk to them, in many ways. It would be seen as being too cozy with them. They won their reelection on their own terms.

The Dispatch: How did the speakers of old spend their time, then?

Huder: From the 1920s through like the 1970s and 1980s, speakers of the House did not take policy positions. If you walked up to Sam Rayburn and you’re like, “Hey, what are you going to do this year?” He would say, “I don’t know. We’re going to work it out between the committees.” Can you imagine walking up to Nancy Pelosi like, “Hey, what are Democrats going to do this year?” And her saying, “I don’t know”? It’s just unfathomable. So they spent their time brokering between powerful committee chairs. Sam Rayburn was negotiating with the Armed Services chair, he was negotiating with the Appropriations chair, negotiating with Judiciary, and he was trying to sort out deals. I mean, not unlike what Nancy Pelosi was doing when she was speaker—but the thing is, they didn’t have all the power to actually move legislation. They were brokering deals between people who had real power. He’s literally just a middleman. The reason they had to be is they didn’t have the authority to do whatever they wanted. They were relying on convincing others.

In the 1960s, there was a really interesting moment that kind of highlighted this point. Sam Rayburn walked up to the Rules Committee chair, Howard Smith, and asked him to bring an education bill to the floor. It had already been passed by the House. It had already been passed by the Senate. All they had to do was just pass the conference agreement, and Howard Smith would not do it. Rayburn was literally pleading with this Rules Committee chair. Howard Smith tells him, “Tell your liberal friends they get the minimum wage bill or nothing.” That’s the kind of power committee chairs had back then. Now, speakers control what’s happening. They can structure the outcome.

The Dispatch: Why have recent House speakers who said they’d give power back to committee chairs failed to really do so? Do they mean it at first, but find out it’s just not actually possible?

Huder: They possibly mean it. The problem is speakers have the power to manipulate the process, and other members know that, and they’re relying on the speaker to manipulate the process. I think it’s a combination of both: They may have good intent, but as soon as the political problems in the legislative process start to pop up, you have members of Congress sort of knocking on their door going like, “Hey, this is a problem for us. Can you please fix it?” And whether you say you want that power or you don’t want that power, you like having it, right? Because if there is something weird going on, you can change the legislation at the last moment. Who’s going to give that up? Who’s going to give up that authority if you have it? You are god of the legislative realm, and you can snap your fingers and change something.

The Dispatch: Do you think it’s also easier for members to have one person to go to instead of having to build relationships with committee chairs and trying to petition them individually?

Huder: I think that helps. But honestly, I think part of it is members just don’t really know how to legislate in the old fashioned way anymore. That was sort of evident throughout the speakership race. You had a situation where Chip Roy and Brian Fitzpatrick were like, “We should have a candidate forum and we should talk about it. And we should see if somebody can get 217. If they can’t, then we drop a candidate and we have another forum and we talk about it.” That’s a normal brokering process. That’s how it’s supposed to work! You don’t need to pass a rule to put in place a normal brokering process! But that’s what they were doing. It’s like they had forgotten how to negotiate and compromise, in many ways. They got to the compromise, but they got to it in a really weird way. I don’t really think they know any different.

The Dispatch: If Johnson is different in meaning what he said about decentralizing power and actually trying to do it, what would we see in the coming months?

Huder: He would need to take power away from himself. And he would need to stop manipulating the Rules Committee, either by taking his own power away from appointing that committee, or just being hands-off on the Rules Committee. He would need to become a broker between committee chairs, rather than a broker between factions of his party. If the Appropriations chair passes a bill, he would leave it alone and let the Appropriations chair handle the negotiations. If he was going to become less powerful, he would stop issuing self-executing rules. He would stop doing closed amendment processes. I don’t think any of this stuff is going to come to fruition. I think it’s going to be more of the same. Even if you change the rules, members are still going to function in the way they’ve functioned for the last 10 years, because that’s what they’ve learned, and that’s what they’ve experienced. And I don’t think you can just decentralize the House uniformly and have much effect within two years, much less a year. I definitely don’t think you can do it if the person with power still has it.

The Dispatch: Is there any merit to the idea that Johnson would have an easier time in the role, with this fractious and slim House GOP majority, if he actually did divest power from himself?

Huder: That’s kind of what McCarthy tried to do. Those bills died on the floor, several of them, over and over and over again. It was pretty embarrassing there at the end of September. Did that help him? No, not really. The other part of this is, I don’t think the members really want the committee chairs in charge, either. Do you think the House of Freedom Caucus wants Kay Granger writing appropriations bills without any of their input? They just don’t like the stuff their colleagues write. Maybe if Johnson actually disempowered himself and said, “I literally can’t change it. They wrote it, you’ve got to talk to them.” That only works if you actually can’t change the bill at the end of the day. But he still has the power, so they’re still going to hold him accountable because he does have the power.

If Kevin McCarthy were really savvy, he would have actually disempowered himself: “I’m not doing this. It’s them, it’s not me. I’ll talk to them, but it’s not me, it’s them.” But he didn’t. He tried to do this two-step, “Oh, I’ll disempower myself, but I’ll keep all the power.” That’s essentially what Johnson’s trying to do. It’s what Paul Ryan tried to do. It’s what John Boehner kind of said he was going to do. It’s what Nancy Pelosi did. You get the idea—everybody says this, and it never happens. And the reason is they still have the power.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.