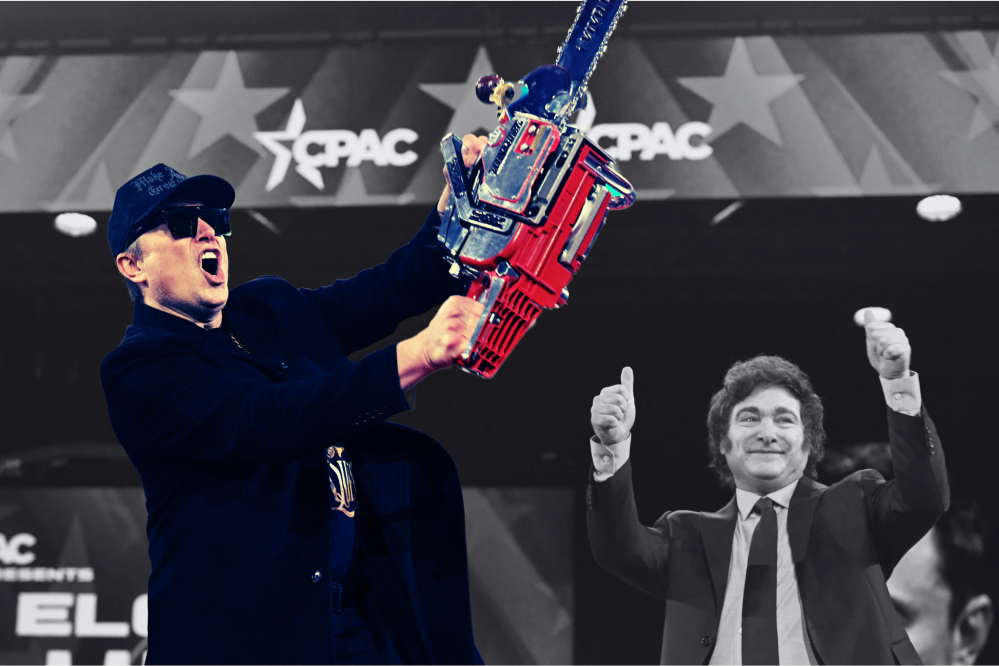

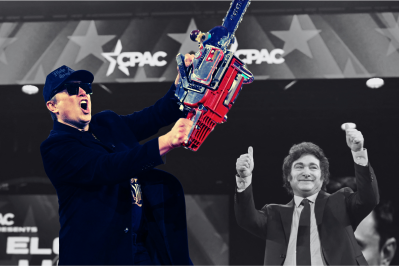

One of the irritating things about DOGE—something that ought to bother conservative DOGE apologists more than it should—is the comprehensive lack of honesty in the thing. The so-called Department of Government Efficiency is not a department, it is really only quasi-government at most, and its aim is not efficiency. It is the right-wing mirror image of those “diversity” offices whose aim is the enforcement of homogeneity and conformity. George Orwell (I hope he is pleasantly surprised by his position in the afterlife) is somewhere laughing his immortal ass off.

The dishonesty is compounded by secrecy. For example, we probably should know who is in charge of the project. There is a person calling himself or herself the ”DOGE administrator” who signs off on paperwork, but no one outside of Musk’s little circle knows who this person is. The only thing the White House will say is that it is not Elon Musk—which means, of course, that it is Elon Musk de facto if not Elon Musk de jure. (Trump says Musk is in charge, contradicting his own people.) People who smile admiringly and pronounce that Trump and Musk just don’t “play by the old rules” ought to think a little bit, if they still can, about what it is they are smiling at.

It isn’t efficiency.

If government efficiency were the end being sought, that would require something the Trump administration and its sycophants have typically avoided: work. Fundamentally restructuring federal agencies and programs requires lawmaking—it is not a task that can be accomplished in any meaningful or durable way through administrative action alone. And such projects are a great deal of work—organizational drudgery and political work, the negotiations that Donald Trump claims to be a master of in contravention of most of the available evidence.

To take an informative example: In the immediate post-9/11 era, there was a push to make our national-security and intelligence agencies more effective by removing interagency barriers and consolidating bureaucracies. The result was the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, which has been partially successful in achieving the goal of its creation. The aim was not to save money, but to make the agencies use their budgets to more effectively pursue their objectives, which is, of course, what efficiency really means.

The people shouting “Defund the police!” a few years ago had a plan that would have reduced spending on law enforcement, but that would not have been efficient—it would have been idiotic. Efficiency is not measured by a budget line—it is measured by ...

the budget line plus the relevant performance metric. I do not think that many of us—even us cranky libertarians—would object to larger education budgets, for example, if those larger budgets produced commensurate improvements in educational outcomes. As any competent corporate manager knows, simply reducing expenditures often is not at all useful in improving business outcomes—including profitability—and, while I am deeply committed in my conviction that everybody who says “We ought to run government like a business!” out to be punctured with something blunt, in this case the broad principle is the same.

The problem with health care and education and the intelligence services isn’t that we spend too much money on them but that we do not get what we want to get for the money we spend. The trains in Switzerland are a lot more expensive than the ones in India, but I prefer the Swiss trains and suspect that many others would, too. (If they can afford them—there’s the rub.) Or you could do things the way Metro North and the New York City subways do, combining European levels of expense (more, in fact) with developing-nation standards of quality and performance. (New York City subway construction costs about 10 times as much, and sometimes even more than that, than similar European projects in countries such as Spain, which is not famous for its efficiency.) McDonald’s could save a lot of money out-of-pocket by eliminating most of its employees or serving (even) lower-quality food, but neither of those would actually be good for its business. Penny wise and pound foolish and all that.

About business regulation, I once observed that the dumbest assistant manager of a McDonald’s knows a lot more about managing his McDonald’s than the smartest regulator in Washington. But Hayekian knowledge problems apply to business endeavors, too. The difference is that markets, when they are allowed to work, are pretty effective when it comes to telling the people at Coca-Cola that nobody likes New Coke. As I wrote to a hypothetical ephebic regulator:

It’s not that there shouldn’t be any regulation. It’s just that we have to keep our expectations excruciatingly modest, because you, Mr. Smith, are not going to be very good at it. But you’re what we’ve got. You don’t know what to do, the elected guys sure as hell don’t know what to do, the whole econo-politico-epistemological deck is stacked against you, and Lloyd [Blankfein; this was post-financial crisis] is dealing. It’s Lloyd’s deck. Common sense is not going to get you through this, and you do not have adequate information to make decisions in the public interest. Nobody does. But here’s the thing: Betamax and the Arch Deluxe and Clairol’s Touch of Yogurt Shampoo (seriously, that existed) just get yanked off the shelves when hordes of people don’t buy them, and the great big milling laboratory of the marketplace tells Joe Businessman, who is really a research scientist seeking social value, to shelve that particular hypothesis and maybe not expect a bonus this year. But there’s no feedback mechanism like that in government, which means that when you do stupid, you do immortally stupid. You might find yourself asking why Alabama has a law against having an ice-cream cone in your back pocket at any time or chaining your alligator to a fire hydrant. (What was the precipitating episode there, Bubba?) You get Americans in the 21st century still paying the temporary emergency telephone tax to fund the Spanish–American War (1897–98). On and on it goes. Forever. Deathless stupidity tends to accrete and clog up the system, over time, and Washington is a factory whose workers produce deathless stupidity like it’s their job, like they’re getting paid for it. Because it is. Because they are.

We free-market types have spent many years arguing that the government does a poor job of trying to run businesses that bureaucrats do not know much about, especially considering the abundance of perverse incentives and lack of good ones influencing the regulatory endeavor. As I wrote above: This is not an argument against all regulation, but an argument for modest expectations. Elon Musk and DOGE now oblige us to examine the other side of that coin, which has rarely been looked at because it is rarely relevant: Business tycoons are apt to do as bad a job when it comes to managing and reforming regulatory agencies and other bureaucracies as those regulators and bureaucrats do when trying to steer complex business endeavors by remote control.

It is obvious that Musk and his disreputable little gaggle of pudwhacking throne-sniffers simply do not know what they are doing: For example, they ordered the dismissal of a bunch of federal employees who were “on probation” because they seem to have thought that this probationary condition was disciplinary rather than a formality related to those employees being new hires. Employees with stellar evaluations were fired in emails that cited their supposed performance problems. In one case a reader passed along, an administrator promoted to a manager position because of his excellent work in a subordinate role was dismissed because he was “on probation” in his new role. Many similar situations have been reported. Ignorance is the natural state of mankind, and most of us will forever be ignorant about most subjects—economists call this “rational ignorance,” which reflects the fact that there is not much reason to learn a great deal about things that do not matter much to you in the near term or foreseeable future and about which you do not have, and never will have, much control or influence. Ignorance can be rational—arrogance rarely is.

Musk and his army of angry nerds have a duty—a professional and patriotic obligation—to be less stupid than they have been. They are creating chaos and damaging worthwhile government programs while simultaneously complicating and pre-discrediting future reform efforts—the ones that will, one hopes, be led and executed by people who can bother to do a little bit of the homework before they start running amok like a bunch of psilocybin-addled maniacs while being led by an actual psilocybin-addled maniac.

And while the habit of personalizing politics ought to be generally resisted, it is worth noting here that Elon Musk is a foreign-born entrepreneur with complex links to foreign governments, self-reported psychiatric problems, and a complicated drug habit. He is not famous for his honesty or personal integrity. He is working, in effect, in secret, with no real oversight or mechanism of accountability.

Historically speaking, Musk has not been exactly a free-market man: Many of his businesses have been government-oriented and subsidy-seeking. (Musk became skeptical of EV subsidies right about the time they started to help Tesla’s competition more than Tesla.) But he knows enough to know how the market mechanism works (which is in a fashion analogous to evolution) to improve products and industries, and that the absence of competitive pressure (leading to product death and firm death) in government means that bad ideas in the public sector can be very long-lived—very nearly immortal.

What he is engaged in right now is only vandalism directed at Kulturkampf ends, but the damage being done will not be very easy to undo, and the precedent being set will last, if not forever, at least until there is a new administration at some point in the future with aims and values that are very different from those of the Trump administration, which under Musk’s influence is creating new weapons to be used by irresponsible demagogues—by other irresponsible demagogues—in ways that will be surprising and horrifying. On top of the damage Musk et al. are doing right now, we should take account of the damage that will be done by others with the present innovations.

A well-governed polity runs on broad, consistently applied rules. We’ve had decades of ad-hocracy, and now we have ad-hocracy on ketamine, which is not a great improvement even if it has a jollier affect.

Economics for English Majors ...

... with an emphasis on the English this week. I recently had a conversation of a kind that will be familiar to many of you. Anonymous Jones remarked that we Americans probably work too much and should spend more time with our families. I concurred, but added that American work habits are not an arbitrary corporate imposition but an aspect of a complex, organically evolved system of production and consumption, and that this cannot simply be rearranged according to the aesthetics and personal sensibilities of would-be social managers. (I’m tons of fun at parties, really.)

Jones’ smugly offered response to all that was: Well, then, maybe we should consume less and be happy with that. Harrumph, etc. To which I added: But you aren’t talking about consuming less—you are talking about consuming more, in the form of leisure time. Jones: We shouldn’t classify spending time with your family as consumption—what kind of monster are you?

And, there it is.

There is a tendency to put the word “mere” in front of rhetoric, as though rhetoric were somehow tawdry or disreputable. I am in the rhetoric business—at least in part—and I was once a teacher of rhetoric, and, from that point of view, I value rhetoric. Rhetoric, intelligently and ethically employed, can help people to understand complicated realities and think through them. (There are some oh-so-worldly Washington types who will roll their eyes at the notion that there are ethical concerns touching rhetoric, as though a mentally normal adult could not tell the difference between putting one’s best foot forward and telling a lie.)

But rhetoric is not the right tool for non-rhetorical jobs. In economics, people often bristle at calling things what they are: “Don’t you dare call Social Security an entitlement—I have a right to those benefits.” (Indeed, you do—one might say you are entitled to them.) Calling spending time with your family and friends (leisure is the common economics term) consumption may make it feel low or unworthy to some people, because that puts it in the same category of things as ordering a pizza or buying a pair of sneakers or going to a movie—but consumption doesn’t actually have a moral quality of its own. You can buy a copy of Penthouse or a copy of City of God, and both are consumption.

How do we know leisure time is consumption? Think of it this way: Imagine a little village in which everybody labors on identical schedules, working 12 hours a day, sleeping eight hours a day, and enjoying the other four as leisure, to spend time with family or read or paint watercolors or play checkers or whatever. And now imagine that some genius comes along with a technological innovation that allows the village to maintain its same level of economic output while working only eight hours a day, making the new arrangement: eight hours of work, eight hours of sleep, eight hours of leisure. The people of the village are better off and—since my hypothetical village is a free-market sort of village—they have a choice about how they want to realize those gains: They can enjoy more leisure or they can work more and raise their material standard of living. They can exchange an hour’s leisure for an hour’s work or decline to do so, which is, economically, the same as exchanging an hour’s work for an hour’s leisure.

Economics is not some magical master discipline of social life, but economics is really, really useful for answering a particular kind of question—economic questions. Rhetoric is not at all useful for answering economic questions—it is useful for intentionally obfuscating what the question is, which is what dishonest people (including those who don’t exactly mean to be dishonest) use it for. I place a very high value on music and think that a life without music would be impoverished, but I wouldn’t try to use music to deal with a problem of forensic accounting or structural engineering or law. You may have heard the famous maxim: “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” I don’t think that is exactly right (Jay Nordlinger writes beautifully and usefully about music) but I sympathize with the notion: You want the right analytical tool for the job.

It doesn’t matter to the economic questions whether we call capitalism capitalism or call it something else, whether we call Social Security an entitlement or a social-insurance scheme, whether we’re comfortable choosing the non-derogatory British sense of “scheme” over the derogatory American sense, whether we call something “rent seeking” or “corporate welfare” or “tapeworming,” etc. None of that matters very much when it comes to dealing with economic dilemmas, and we shouldn’t waste our time pretending that it does.

Words About Words

I beat up on my friends at National Review a little bit over their not-very-good-at-all DOGE editorial. But the piece started off as a rant about my irritation with the “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” cliché. In addition to being banal, the phrase is almost always used dishonestly—as a way of asserting, without quite arguing, that the defects in a particular way of doing things do not justify existing criticism of that method. E.g., Fay Johnson writing in the New York Times, incompetently, about online moderation:

I’ll be the first to acknowledge that no moderation system is perfect. I’ve sat in rooms where we have debated where to draw the line, knowing that to catch most harmful content we would also inadvertently remove innocent posts. Moderators can be unsure whether a satirical post crosses the line into hate speech or if a post expressing earnest concern about vaccine efficacy has veered into misinformation. There is no universal consensus on what constitutes “harm,” and without careful calibration of policies and the machine-learning models trained to enforce them, mistakes happen.

But we cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

This is an excellent example of the kind of intellectual dishonesty I mean. No one ever insisted that Facebook or Twitter have a moderation system that is “perfect,” and they were not criticized for failing to meet the standard of perfection. The question was not whether the perfect should be the enemy of the good but whether what they had was, in fact, any good. The answer, broadly, is that it wasn’t. Partisanship, bias, and giving in to every idiotic voguish political mandate that a Bryn Mawr sociology student could dream up did more harm than good. We are seeing, in part, the results of that today.

To take the go-to example, efforts by online platforms to suppress the New York Post’s reporting about Hunter Biden’s laptop in the runup to the 2020 presidential election were not imperfect—they were corrupt. They were not intended to protect the truth but to protect Joe Biden’s political interests. They were not aimed at mitigating harm, unless “harm” is defined as anything that might hurt the electoral prospects of Democratic office-seekers or further the political interests of Donald Trump. As loathsome as Trump and his sycophants are, that is not a very good definition of the public interest, harm, or safety. Nobody thinks that Amazon banned Ryan Anderson’s book on transgender controversies because it is dangerous—Amazon is now selling the book, and the book is the same book it was six months ago. The thing that has changed is the political environment.

The problem is not that—oh, the weaselly language—“mistakes happen.” The problem is that what happens isn’t a mistake at all but an intentional program of suppressing views because they are unpopular and disliked by the people who have the power to suppress them. This is why we get lectures about rigorous standards of scientific evidence from newspapers that publish horoscopes and every manner of “wellness” quackery and flim-flammery. It is not a question of truth or falsehood—it is a question of what, and whom, the little suppressors dislike.

This is not a case of allowing “the perfect to be the enemy of the good.” It is a case of bad actors doing bad things for bad reasons. The fact that Johnson and her Times editors refuse to deal with that head-on is why they enjoy so little public trust.

In Other Wordiness ...

As a political matter, tax cuts simply are not a top priority for the American people broadly, the working class that now forms the core of the Republican coalition nor even the Republican Party itself.

Not ... nor doesn’t really work. What you want is neither ... nor: “Tax cuts are a top priority neither for the American people broadly nor for the working class.”

The analysis found that v-Fluence was “not subject to the GDPR”, but recommended v-Fluence handle “EU personal data consistent with the requirements of the GDPR in the event the Regulation is deemed to apply”, the company said in a statement. One of the recommendations was removing the profiles, the company said.

v-Fluence will continue to “offer stakeholder research with updated guidelines to avoid future misinterpretations of our work product”, according to the company statement.

Capitalize the first word in a sentence, even when that word is part of a proper noun that is usually styled lowercase. You may write bell hooks or e.e. cummings or iPhone in the middle of a sentence, but at the beginning of one, capitalize the first word. The fundamental conventions take priority over specific eccentricities—to capitalize at the beginning of a sentence is not to change the way e.e. cummings styles his name but simply to write formal English as formal English is written. Bell hooks may have hated semicolons (hypothetically) but that wouldn’t have any bearing on whether a sentence about her should have semicolons in it.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

The Trump administration is, as expected, incoherent and self-contradicting. But if it has an identifiable throughline right now, it is this: The Trump administration acts consistently in accord with Moscow’s interests, even where these conflict with American interests. I recommend to you James Kirchick’s latest, in the New York Times:

Since the onset of the Cold War 80 years ago, American presidents of both parties have understood the necessity of a Germany reliably rooted within the Western alliance. From West Germany’s controversial rearmament in the early 1950s to the deployment of American Pershing missiles on German soil three decades later and the rallying of support for Ukraine today, the possibility of the European Union’s most populous country's adopting a position of strategic neutrality, of “equidistance” between America and Russia, has been a perennial concern. For the United States to put its considerable clout behind a German political party whose leaders minimize Nazi crimes, portray their country as a victim of scheming outsiders and parrot talking points from the Russian Foreign Ministry would be a blunder of historic, and potentially catastrophic, proportions.

One way of looking at this is that Trump et al. simply prefer to serve Russian interests. They prefer men such as Putin to men such as Zelensky, and would prefer a United States that more closely resembles Russia to one that more closely resembles Ukraine. Another way—more plausible, in my view—is that this is what happens when a weak man who doesn’t know what he believes encounters a ruthless man who knows what he wants. Trump’s subordinance to Putin is instinctual. Americans may not notice this, because Americans are not inclined to notice that kind of thing. But the rest of the world is noticing. Weakness is provocative—and one shudders to think what it is that Trump’s weakness will provoke.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.