One of the really knotty problems with our public debates is that we often are having two or three debates at the same time, and it is easy to get confused about which question is actually in dispute at any given moment.

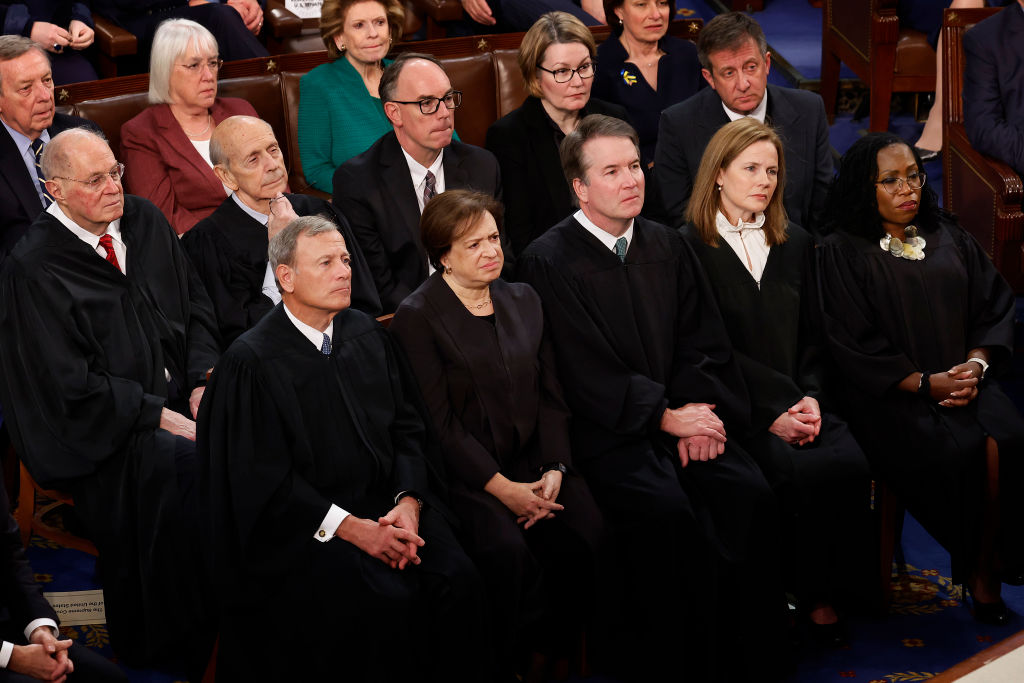

Take, for example, the recent debate about racial preferences in college admissions: The question before the Supreme Court was only a legal one—not that you’d know it from the campaign-style rhetoric of Ketanji Brown Jackson or Sonia Sotomayor!—to wit, whether the law permits what Harvard and the University of North Carolina were doing, or whether that amounted to unlawful racial discrimination. The majority of the Supreme Court rightly found that this racial discrimination was unlawful. A second question—an unrelated question from the point of view of a Supreme Court justice who is actually doing his or her job instead of trying to act as an unelected legislator—is whether racial-preference policies such as those that had been implemented at Harvard are good policies. A third question—never quite explicitly discussed—has to do with “legal consequentialism,” the notion (which has official legal standing in some countries, such as Brazil) that legal questions per se should be made subordinate to utilitarian calculation. As the Brazilian statute puts it, “a decision shall not be made based on abstract legal values without considering the practical consequences of the decision.”

The consequentialist point of view is an invitation to conflate the question of what the law actually says with the separate question of what the law ought—according to … somebody—to say. Justice Jackson’s remarks about the affirmative action cases offered an illuminating case of vulgar consequentialism. Never mind the law, she insisted, affirmative action is a policy that “saves lives.” For example, she noted, the survival rate for high-risk black newborns is more than double for those with black physicians than for those with non-black physicians. That is an extraordinary claim, one that is interesting in that it is transparently untrue and preposterous on its face. African American newborns do, indeed, have higher infant-mortality rates than do those of other races, but the overall rate of infant mortality among black newborns is 894 per 100,000, a survival rate just a little above 99 percent. (Hooray for that worst health care system in the developed world.) The only way the survival rate could double for newborns under the care of black physicians would be if the survival rate were less than 50 percent—as a mathematical matter, the survival rate necessarily tops out at 100 percent.

The research Justice Jackson cited does not say what she says it says, and, given her misunderstanding of it, one suspects that she did not read the paper at all but instead read an amicus brief based on this ideologically distorted (and, on some points, originally erroneous) report in the Washington Post. Ted Frank, writing in the Wall Street Journal, takes this nonsense apart in a very precise and easily understood way.

Justice Jackson is here engaged in the silliest and most unserious version of consequentialism: “People will die!” Sen. Elizabeth Warren is the textbook practitioner of this: Support Republican tax-cut proposals or Republican health-care policies and “people will die!” One can come up with a chain of consequences in favor of—or against—practically any policy proposal and use it to argue that, unless you get your way, people will die. As it turns out, this stuff is pretty easy to turn on its head. The research Justice Jackson cites doesn’t say what she says it says, but it does find that the patients of black pediatricians have higher overall mortality rates than the patients of non-black pediatricians. If we take Justice Jackson’s line of argument seriously, then we would have to consider the possibility that having any black pediatricians at all means that children will die. But we do not have to take that line of argument seriously, because it does not deserve to be taken seriously.

Justice Jackson is herself one personification of how easy it is to misunderstand—or misrepresent—the evidence for or against racial preferences. If race is all you take into consideration, then, yes, it surely is the case that African Americans as a whole are less likely to enter elite law schools and become highly successful attorneys than are members of many other groups. But we live in a complex society in which race is one factor—an important one—among many. I have often teased Mitt Romney about being the son of a moderate Republican governor, multimillionaire businessman, and failed presidential candidate who overcame the obstacles of his birth and grew up to become a moderate Republican governor, multimillionaire businessman, and failed presidential candidate. Romney is one apple that did not fall very far from the tree. Justice Jackson is another. Her parents were college graduates and people of consequence in Miami, where she grew up. Her mother was a high school principal, her uncle chief of police in Miami, her father a successful school-board attorney.

Justice Jackson replaced Justice Stephen Breyer, whose father also was a school-board lawyer. She went to the same law school as Justice Breyer. (Amy Coney Barrett of Notre Dame Law is the only justice who did not go to Harvard or Yale for law school.) She was an editor at the same law review as Justice Breyer. She clerked for Justice Breyer. If you cannot see the family resemblance between the two justices, then you are not looking at the scene with the right kind of eyes.

And it is not as though she started at the bottom and got there thanks only to racial preferences: Justice Jackson went to the same high school as Jeff Bezos.

So, yes, she was the first black woman on the Supreme Court—and she was the 22nd from Harvard Law. In that sense, she’s not exactly a socioeconomic trailblazer—she’s more of a Rufus Wheeler Peckham, another Democratic political activist who was willing to set aside principle when achieving his favored political outcome demanded it.

(Upon being nominated to the Supreme Court, Peckham remarked: “If I have got to be put away on the shelf, I suppose I might as well be on the top shelf.” Also: You don’t meet as many men named “Rufus” as you once did.)

Socially, economically, educationally, Justice Jackson is precisely the sort of person you’d expect to see end up on the Supreme Court. And, before that, she was precisely the sort of person you’d expect to see end up at Harvard Law. One wonders what great experience of diversity she brought to all the other children of lawyers and school administrators she encountered at Harvard Law. It is true that she had an uncle who was arrested for distributing cocaine—if an uncle with a drug-crime issue is what it takes to bring some cherished diversity to the Ivy League, then young Robert Biden II can rest easy, for the way has been made straight for him.

There is one member of the Supreme Court whose personal story really is radically different from that of the typical elite lawyer or federal judge. As such, it is entirely unsurprising that it is Clarence Thomas who has been the most clear and plain about the shortcomings of using race as a proxy for that more complex and more meaningful kind of diversity that really does enrich public and private life.

Justices of the Supreme Court tend to be at their worst when they are acting as amateur sociologists as a prelude to acting as freelance legislators. Justice Jackson’s sloppiness with the scholarly evidence here is one of many examples of that. Judges are legitimately empowered to do one thing and one thing only: sorting out certain consequential legal questions. Using a seat on the Supreme Court to pursue private notions of justice and private political agendas not only is not a legitimate part of the justice’s job—it makes it impossible to do that job at all. I wasn’t being facetious when I suggested that Justice Jackson resign her seat on the court and seek one in Congress—if she wants to make the laws, then let her first seek election as a lawmaker. The job she has is difficult enough without moonlighting as a legislator.

But what about that consequentialism? The law has real-world effects—shouldn’t judges take those into account when making decisions? I don’t think so, and I don’t think that many other people would, either, if they would think it through. Making legal decisions based on their likely practical effects ultimately means nothing more or less than that judges should subordinate what the law says to their own private notions—which are necessarily limited, short-term, and held without direct political accountability—and do whatever seems right to them in the moment. We write down our laws precisely to avoid having them be creatures of a moment and only a moment. The First Amendment has been the law of the land for 232 years, during which there were many moments when those with power were inclined to violate the protections enshrined therein—and even tried to do so from time to time, with occasional success. (It is good to remember that it fell to the conservative Warren G. Harding to commute the sentence of the socialist Eugene V. Debs, branded a “traitor to his country” by the progressive Woodrow Wilson and locked away on sedition charges for criticizing the military draft.) If you read the history, you will appreciate how many of the arguments against free speech—and against other civil liberties—were consequentialist in character. That has been the case from Eugene V. Debs all the way back to Socrates.

And Ketanji Brown Jackson is far from the first Supreme Court justice to make a practical argument for discriminating against people of Chinese origin.

And Furthermore . . .

Racial opinions more than four minutes old often look pretty bad. In his Plessy dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote:

I am of opinion that the state of Louisiana is inconsistent with the personal liberty of citizens, white and black, in that state, and hostile to both the spirit and letter of the constitution of the United States. If laws of like character should be enacted in the several states of the Union, the effect would be in the highest degree mischievous. Slavery, as an institution tolerated by law, would, it is true, have disappeared from our country; but there would remain a power in the states, by sinister legislation, to interfere with the full enjoyment of the blessings of freedom, to regulate civil rights, common to all citizens, upon the basis of race, and to place in a condition of legal inferiority a large body of American citizens, now constituting a part of the political community, called the ‘People of the United States,’ for whom, and by whom through representatives, our government is administered. Such a system is inconsistent with the guaranty given by the constitution to each state of a republican form of government, and may be stricken down by congressional action, or by the courts in the discharge of their solemn duty to maintain the supreme law of the land, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.

Pretty solid stuff. But he also wrote—in the same dissent:

There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race.

He signed the dissent in Wong Kim Ark, which argued that people of Chinese origin could not become U.S. citizens because they were, as a practical matter, impossible to assimilate:

Generally speaking, I understand the subjects of the emperor of China—that ancient empire, with its history of thousands of years, and its unbroken continuity in belief, traditions, and government, in spite of revolutions and changes of dynasty—to be bound to him by every conception of duty and by every principle of their religion, of which filial piety is the first and greatest commandment; and formerly, perhaps still, their penal laws denounced the severest penalties on those who renounced their country and allegiance, and their abettors, and, in effect, held the relatives at home of Chinese in foreign lands as hostages for their loyalty. And, whatever concession may have been made by treaty in the direction of admitting the right of expatriation in some sense, they seem in the United States to have remained pilgrims and sojourners as all their fathers were.

In much the same vein, you can read Mohandas K. Gandhi early in his career arguing that the British were wrong to discriminate against Indians in the British Empire because doing so unfairly reduced Indians to the status of Africans, who were, in his view, “savages” fit only for lives of “indolence and nakedness.”

Quandoque bonus dormitat Homerus. The Mahatma, too.

Economics for English Majors

Who could have seen this coming? Other than your favorite retired theater critic, I mean.

Headline: “Interest Costs Will Grow the Fastest Over the Next 30 Years.” The guts of the story:

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) long-term baseline, federal spending as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will grow to 29.1 percent over the next three decades. Driving a large part of that growth is spending on interest payments to service the national debt.

Net interest payments hit a nominal dollar record of $475 billion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 and will nearly triple by FY 2033 to $1.4 trillion, growing to $2.7 trillion by 2043 and to $5.4 trillion by 2053. As a share of the economy, net interest will rise from 1.9 percent of GDP in FY 2022 to hit a record 3.2 percent by 2030 and more than double to 6.7 percent by 2053.

By 2051, spending on interest will be the single largest line item in the federal budget, surpassing Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and all other mandatory and discretionary spending programs.

Think about that: In only a few years, the single biggest federal expense will be paying interest on spending that will, at that point, be many decades in the past. It may be a lot of fun to spend money on bridges to nowhere and free false teeth for everybody in the here and now, when politicians can watch all that money slosh around in their districts, but it is a heck of a lot less fun to be spending that money on bridges to nowhere build 70 years ago.

I suspect that Republicans are about to have a couple of good elections, and the reason I suspect that is the fact that the New York Times editorial board has suddenly taken an interest in fiscal responsibility: “America Is Living on Borrowed Money” the Times editorial thunders. (Debt, like homelessness, has a way of creeping up to the front page from way back on A26 when Republicans are in power. It is a dismal tide, indeed.) The Times editorial being a Times editorial, it has a cheap—and erroneous—class-war element baked in, with the editors complaining: “Rather than collecting taxes from the wealthy, the government is paying the wealthy to borrow their money.” That is, as the economists say, horsepucky. The old days of rich people sitting on big piles of T-bills—“lapt in a five per cent Exchequer Bond” like the old British aristos—are long, long gone. The major holders of U.S. government debt are central banks around the world (including our own Federal Reserve), followed by mutual funds, ordinary depository banks, state and local governments, and pension funds. We aren’t paying Scrooge McDuck to borrow his ducats—we are paying retired California schoolteachers, cops in Philadelphia, garbage collectors in Chicago, etc. Lots of good-ol’ regular-folk “Real Americans™” on Uncle Stupid’s very long list of creditors. Sure, Wall Street gets a cut—you don’t move that much money around, tons of the stuff, without paying the freight.

Most of the money going out of the Treasury spillways is either some form of income support (Social Security, traditional welfare, health-care subsidies), military spending, or, as the world seems to be discovering, interest on money already spent. And, as you may have noticed, we are not in an existential fight for our lives with Nazi Germany or a Cold War with the Soviet Union; we are not facing some domestic emergency that is driving spending, either: Even if you account for COVID spending in the broadest way, it’s a drop in the ocean. (Never mind that many of our economic crises over the past 30 years have been driven by policy decisions in Washington rather than by exterior factors.) As I have been writing a bit about lately, much of that spending has been marketed as “investments.” But if that spending really was an investment rather than simple consumption, then we would expect public debt as a share of GDP to be declining—the benefits, the return on the investments, would exceed the cost. In fact, the opposite has happened: public debt as a share of GDP today is about four times what it was 50 years ago. Artificially low interest rates have kept net interest as a share of GDP relatively low—much lower today than it was in the 1980s and 1990s—but inflation has necessitated a change of course with interest rates.

We’re spending like we’re in an emergency when there is no emergency, and we double down on that when there is an emergency. If we keep on our present course, debt-service expenses will exceed our tax revenue and may exceed the revenue we can successfully collect even if the Times editors get their way and a big class-war tax hike is enacted.

What happens then? Ask the archangel Gabriel.

Words About Words

About the above: It’s “to wit,” not “to whit.” Wit comes from the Old English witan, “to know,” from the proto-German witanan, “to have seen.” This wit, unlike the more common modern English wit, as in the quality for which Oscar Wilde was famous, is a verb, not a noun. The original phrase was “it is to wit,” meaning, roughly, “as it is known,” and, later, “namely.” The Latin videlicet, viz. to the lawyers, means roughly the same thing.

The other one, whit, comes from the Old English na whit, meaning “no amount.” We still use it in roughly that form, as in “not a whit of evidence.”

So, when it comes to “nameless,” keep it whitless, lest you appear witless.

Elsewhere

Meta vs. Twitter is the corporate Iran-Iraq War you’ve been waiting for. In the New York Post, I’m rooting for casualties.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

I have often remarked that everybody would be 100 percent down with capitalism if not for their experience with a few companies in a few industries, mostly heavily regulated, low-competition industries such as airlines, health insurers, and banks. I’ll write up my recent tale of woe with British Airways at some point, if only because I know how much sympathy I’ll generate with stories about disappointing business-class travel to Lake Como. The trouble with airlines isn’t just airlines, of course—it is the FAA and other regulators, airport authorities, and much more, not to mention the vast constellation of incontinent recta that is the traveling public. Government and industry analysts have estimated that flight delays cost Americans some tens of billions of dollars every year, but the real number must surely be much higher, inasmuch as the inability of airlines to keep to a schedule has changed both business and consumer behavior: For example, a nonprofit I used to work for insisted that participants flying in for events show up a day early—even if your event was at, say, 7 p.m., you were not allowed to fly in that morning, because of the likelihood that you’d be delayed and miss your appointment. For us, that meant hundreds of thousands of dollars a year in additional travel costs, and we were kind of a small deal. As with traffic congestion in the cities, anybody who could plausibly address that problem would have the thanks of a large and diverse constituency. But, hey, let’s talk more about “cultural Marxism” and “white privilege.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.