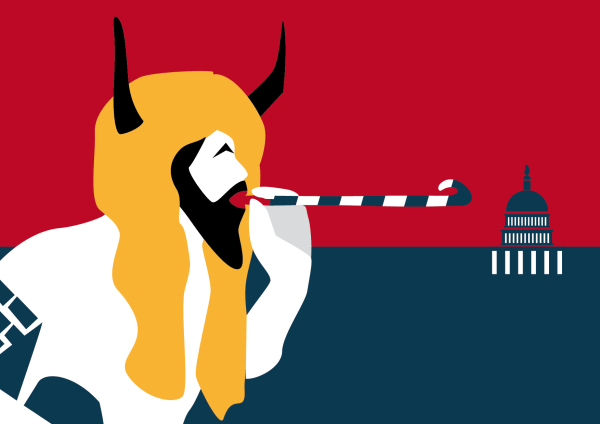

What sort of man is Donald Trump?

He is a felon, among other things.

He says he was wrongly convicted. But people who have been convicted of felonies sometimes find their way into office. There’s Yusef Salaam, for example, one of the “Central Park Five” whose execution Donald Trump once called for in a New York Daily News ad. Trump was trying to make a name for himself as a potential political figure, and Salaam was charged in the horrifying “Central Park jogger” case. Trump’s ad was headlined: “Bring Back The Death Penalty. Bring Back Our Police!” and it concluded that those convicted of crimes should receive tough sentences so that they might “serve as examples so that others will think long and hard before committing a crime.” Salaam was convicted in 1990, released from prison in 1997, and saw his conviction overturned in 2002. He was 15 when the crime was committed and 40 when New York paid a settlement to him and the others convicted in the crime to resolve their complaints. He currently sits on the New York City Council.

Trump says he stands by his statements about Salaam and the others. He believes himself to have been railroaded, but apparently does not believe it is possible that others have been unjustly convicted—except for those convicted of crimes related to the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021, whom he hails as “heroes” and describes as “political prisoners.” Trump enjoys the company of some criminals—corrupt former New York Police Department Commissioner Bernie Kerik and former Hells Angels chapter president Chuck Zito—but other criminals are, apparently, just from the wrong class of criminals.

The favorite of evangelical America also enjoys the company of pornographic performers—and not just Stephanie Clifford, that ample packet of girl trouble who is the proximate cause of the business-fraud mess Trump got himself into. Which, again, raises the question:

What sort of man is Donald Trump?

About the underlying facts of Alvin Bragg’s case, there was never any serious question. Trump conducted a sexual liaison with the woman known professionally as Stormy Daniels—at the time a pornographic performer looking to move beyond sex videos into another kind of entertainment career—while his wife Melania, the future third lady, was at home tending to their newborn son, Barron, who is named after the imaginary friend Trump invented to lie to the New York Post about his sex life. (This is something totally normal and mentally well-adjusted people do all the time: invent imaginary friends to falsely inform the tabloid-reading public that one is dating, say, Carla Bruni.)

Trump’s history with women is of course a weird and creepy one. He has a habit of getting involved with women with whom he has a financial relationship, and, as ABC News put it, Stormy Daniels says their “relationship ended when Trump told her she would not be cast on The Apprentice.” Trump mixes up his money problems with his women problems—he is one of those guys who every now and then slams his dick in the cash register. Melania Trump—who a few years ago won a defamation case against the Daily Mail that had claimed she worked as a high-end escort before her marriage to Trump—posed for skin-magazine photographs that might charitably be described as lesbian-porn adjacent—and, indeed, Trump himself has made cameo appearances in three pornographic films produced by Playboy Enterprises. Melania was an employee of Trump’s dodgy and now-defunct modeling agency, which, according to several former employees, employed illegal immigrants and serially abused the H1-B visa program.

Trump’s transparent attempts to buy women often have gone spectacularly wrong: One of his many stupid vanity projects was his acquisition of the Plaza Hotel in New York, a bad plan he made worse by putting his then-wife, Ivana, in charge of the project as president of the company. The couple drove New York’s most famous hotel into a state of financial ruination, and Trump ultimately was bailed out by Saudi princeling Al Waleed bin Talal. The politician and the princeling later got into a Twitter spat—because this is Donald Trump we’re talking about—and the Saudi tycoon mocked Trump, noting that he had bailed him out twice (he had bought a yacht from Trump to provide a much-needed cash infusion when he was in the middle of an earlier business crisis, because Trump was pretty much always in a business crisis) and suggested that there might be a third time.

In addition to his troubled modeling agency, Trump was an investor in beauty pageants. One of his wives, former pageant contestant Marla Maples, was installed as host of the Miss Universe and Miss USA pageants under Trump’s ownership. Trump and Maples also appeared together as celebrity guests at WWE WrestleMania VII.

What sort of man is Donald Trump?

Trump insists that the case against him in New York was a sham, that it was—his favorite word—“rigged,” that the judge is “corrupt,” etc. But jury trials and elections are the two most democratic events in American life—the two realms in which the people take the most direct role in government. Of the two, jury trials are the more reliable, though these, too, are far from perfect or predictable. Jurors, unlike voters, are made to engage in deliberation, forced to sit through presentations of evidence, given some instruction regarding the relevant matters of law, etc. Trump is now the funhouse-mirror image of O.J. Simpson, though we can be fairly sure that he will not spend his remaining years in a quixotic search for the “real” offenders—you know: the guy who actually carried out a sad hotel-room tryst with an enterprising pornographic performer, paid her hush money, and then misrepresented the expense in his business records in order to further his political ambitions without having to account for the outlay as a campaign expense.

Like any conservative who takes the word conservative seriously, I am skeptical of the kind of innovation Alvin Bragg engaged in to make his case against Trump, and though the outcome has been jury-ratified, it may very well be that Bragg’s case does not survive appeal. Bragg is less ambitious in his legal innovations than is, say, Donald Trump, who argues that presidents must enjoy absolute legal immunity for criminal acts, a privilege found nowhere in the Constitution—which is itself a document that Trump argues must be set aside when it comes to his securing his own political interests. This being a state conviction, Trump cannot do what he hopes to do in the matter of the other felonies of which he may be convicted: use one democratic process (the presidential election) to undo the results of another (the trial). He apparently means to pardon himself if elected—another questionable legal innovation that might be tested.

About the legal underpinnings of the Bragg case and the other cases against Trump, I suppose there are many legitimate questions that remain. But the most important question—what sort of man is Donald Trump?—has been answered.

And what sort of men are Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, Mike Pence, Rev. Robert Jeffress, Kevin Roberts, and Trump’s other sycophants and enablers?

Words About Words

Actors famously go wrong when asked to speak extemporaneously. There is a reason they make a living speaking words written for them by other people. But film directors often miss the mark, too. A reader writes in to note director Jonathan Glazer’s remarks at the Academy Awards:

Right now we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness in a holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people.

And asks:

Perhaps I’m wrong, but doesn’t “refute” mean something like “to prove that a thing is false”? What has Glazer done to refute anything here? Presumably refuting his Jewishness would make his statement even less impactful, if that’s what he was trying to do.

People engaged in political rhetoric throw around words such as refuted or disproved or discredited in an irresponsible sense, as though by merely declaring that something has been refuted, disproved, or discredited, that the thing would magically be, in fact, refuted, disproved, or discredited. “Refute” does indeed mean “to prove wrong by argument and evidence,” rather than “reject,” which is how Glazer seems to be trying to use it. There is something academic and intellectual-sounding about the word “refute,” and I suspect that Glazer was simply taken in by that.

The whole sentence is, of course, a grammatical and syntactic mess. It contains many evocative words—holocaust, hijacked, etc.—but doesn’t quite mean anything.

The director presumably knows where to go to hire writers. He should do so. It would be money well-spent, if only to avoid sounding like an imbecile.

Another reader asks: What’s up with personal friend? Aren’t all friends personal friends? What would an impersonal friend be?

I suppose there are impersonal “friends,” “friends” at some remove: the Friends of the Manhattan Beach Library and organizations such as that, the colleagues known as “friends of the podcast” or “friends of the magazine,” that sort of thing. And I suppose many of us have longstanding, friendly relationships with professional acquaintances that are something like genuine friendships but without the element of non-professional socializing. “Work friends” may be distinct from “personal friends.” That is probably what people are trying to get at.

Of course, “work friends” may not really be “friends” in the deepest sense, whatever friendly feeling we have toward them. There are people I have known for 20 years, people I think of as friends and whom I always am happy to see when I see them, but I don’t have their phone numbers, or, if I do, I don’t call them up on a Wednesday afternoon just to check in and see how they are doing, and I don’t invite them to lunch without a professional reason. My oldest friend is someone I’ve known since we were both about 4 years old, and, if I hadn’t talked to him in a year and he suddenly called me up in the middle of the night in some kind of emergency, I’d get up and go, no (well, few) questions asked. But that’s not a personal friend. That’s just a friend.

Maybe a personal friend is someone who started off as something else—maybe as a work friend—before the relationship deepened. I have a few of those: people who once were only colleagues who have become real friends. I suppose that would be a useful distinction: “We worked together for years before we really became personal friends.”

Complicated subject, friendship. Important subject.

Also: I’m writing from Edinburgh, Scotland, where my Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) colleagues and I (some of whom are personal friends) are celebrating (a little late) the 300th birthday of Adam Smith. And here, on a menu, I read the words: vegan haggis.

Haggis isn’t bad. But it sounds weird—both because of what’s in it and because the word haggis just sounds funny, like kumquat. Iain Murray of CEI, who was having the classic haggis, tells a funny story about Noël Coward, stuck on an elevator with a boor who kept demanding: “Say something funny! Say something funny!” Coward said nothing until, departing the elevator, the famous wit turned to the pest and said:

“Kangaroo.”

Kangaroo is a funny word. Haggis is a funny word. Sheboygan is a funny word. Vegan haggis is a pretty good illustration of how easy it is to add one word and make something famously unappetizing-sounding sound even more unappetizing. Vegan haggis: Ye gods.

Economics for English Majors

Vegan haggis is an example—a bad and disastrous example!—of the economic idea of substitution. In theory, vegan haggis is a substitute for haggis—you might opt for one instead of the other, in some imaginable circumstance. The possibility of substitution can be understood by means of cross-elasticity of demand. If x really is a good substitute for y, then an increase in the price of x should produce an increase in demand for y. Example: If the Toyota Corolla and the Honda Civic are pretty good substitutes for one another—and I will take a second here to observe that one of the miracles of capitalism is that these modestly priced cars we have today are far better than anything a sultan or tycoon could buy at any price 50 years ago—then an increase in the price of Corollas should produce an increase in the demand for Civics. People want a car, and the need they have can be satisfied about as well by a Civic as by a Corolla, so people who might have bought a Corolla choose a Civic instead if the price of a Corolla goes up. That’s a substitute. Some goods are near substitutes, and a few are perfect substitutes.

I suspect that if we ran a pricing experiment, we’d find that vegan haggis is not a substitute for haggis at all.

But, then, what is?

Furthermore …

Elsewhere …

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here. My most recent guest: Nick Gillespie of Reason, who has had some truly awful jobs in his life. I really enjoyed my conversation with Nick, and I think you might, too.

In Conclusion

Donald Trump is now a convicted felon. He faces several other trials on charges that are in some cases much more convincing than those brought by Alvin Bragg. More convictions are likely. I’d like to remind my Republican friends of what I wrote on May 4, 2016, at 2:20 a.m.: “Remember, you asked for this.”

Well, didn’t you?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.