Two new reports on the condition of the U.S. labor market point out just how big a challenge America has in keeping its economy staffed. The first, by Emsi labor market economist Ron Hetrick along with Cassondra Martinez and Hannah Grieser, focuses attention on the underlying building blocks of the labor market: demographic pressures, a pandemic-fueled rush to retirement, and collapsing immigration rates as our chief challenges. The second, a paper by Harvard economists Alex Domash and Larry Summers, precisely quantifies the sources of the labor shortage and connects it to rising inflation. The full picture suggests that concerns about a wage-price inflation spiral are well justified.

Emsi’s new analysis builds on its 2021 report, The Demographic Drought: how the approaching sansdemic will transform the labor market for the rest of our lives. That report, which I wrote about here, was an economic retelling of how declining fertility is colliding with accelerating retirements to make labor shortages a permanent feature of American economic life. Emsi’s new report narrows this analysis and applies it to immediate post-COVID-19 conditions. While our working age population is still growing, it isn’t growing nearly fast enough to keep pace with general population growth or labor market demand. The authors chalk up the gap to COVID-related work hesitancy, early retirements, childcare shortages, too-generous public subsidies for non-work, and a precipitous drop in immigration levels. To return us to pre-pandemic employment levels, we need 875,000 more workers right now. To get us to a steady-state workforce that catches up with the demands of a growing population and economy, we need around 3.2 million more workers, a figure that will continue to grow over time.

The largest chunk of “missing” workers—those who were in the workforce before COVID-19 and arguably should be now—is accounted for by 2.6 million early retirements in the over-55 demographic. Lower immigration levels are another significant factor. Legal immigration reached a recent peak of just more than1 million in 2015 before falling to just over 200,000 in 2021. Counterintuitively, anti-immigration sentiment spiked precisely as immigration was collapsing . A recent Gallup poll found that 35 percent of Americans want less immigration (compared to 19 percent in 2021) while the number of Americans who support more immigration fell from 15 percent to 9 percent. This suggests that trying to solve the labor shortage by welcoming more workers from abroad—one of the fastest ways to grow the labor pool—continues to face significant political hurdles.

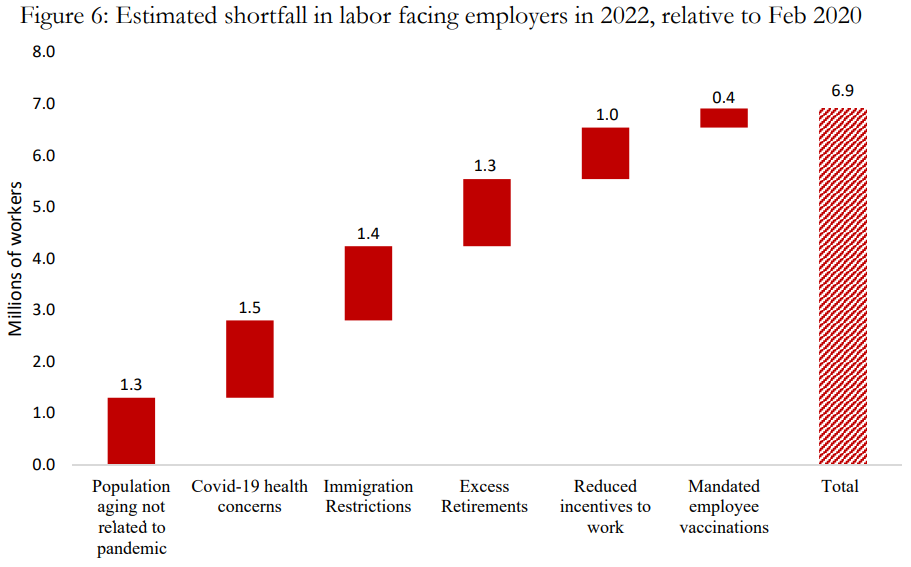

The Domash and Summers analysis is useful for understanding how demographics and labor flows are affecting wages and inflation. They begin by saying the standard unemployment measures are less helpful in understanding labor market tightness than “firm-side” vacancy and quit-rate measures. Our nominal unemployment rate as of January was 4 percent, indicating modest slack in the labor force. Firm-side data tells a different story. Using historically high levels of openings and job quits, Domash and Summers say the functional unemployment rate is below 2 percent. While varying in degrees of importance, they attribute labor market tightness to many (but not all) the same factors as Hetrick, spreading it relatively evenly across excess retirements, COVID health concerns, immigration, and demographics.

One interesting point of departure between the two papers is the relative emphasis the authors place on the role of public subsidies like stimulus payments and more generous pandemic unemployment insurance compensation. Unlike Emsi, which points to record high, stimulus-driven savings rates as a key factor keeping people out of the workforce, Domash and Summers offer a more complex analysis. Workers, they say, are signaling that money may not be at the forefront of their considerations right now. Instead (or, perhaps, in addition), they say, workers “tastes” have changed with increasing demands for more flexible working arrangements and, at times, different work altogether. The authors cite recent polling that shows nearly half of U.S. workers are reconsidering the type of job they want. Twenty-six percent want a job that provides remote or hybrid working options. Nearly 40 percent of workers say they would consider quitting if they couldn’t work from home. Combined, these factors have increased the “reservation wage” (i.e. the wage below which workers will decline employment) by 9.3 percent. Tight labor markets make for choosey workers, and choosey workers lead to tighter, less predictable (some would say, frantic) labor markets with workers churning through multiple jobs in search of higher wages and better benefits.

Depending on your perspective this is either a virtuous or vicious cycle, or perhaps a virtuous cycle that has turned sour. Especially for those at the lower end of the labor market, nominal wages have risen fast, as much as 4.5 percent since December 2020. That is the fastest since 1983, but those gains are being offset by inflation in the prices of goods and services they purchase which is trending as high as 6.8 percent, a 39-year high. All things considered, recent analysis shows all sectors have below trend in real wage growth compared to pre-pandemic. This sort of trend hits those at the lower end of the wage scale the hardest because they spend the largest portion of their income on consumable goods. Without stabilizing the labor supply chiefly through persuading people to “unretire” or figuring out how to import more workers from abroad without setting off a political firestorm, the case for a wage-price spiral begins to look more compelling.

And here’s the real kicker: Assuming we could grow the labor force, Domash and Summers say, it would, in good hamster-wheel fashion, inject more money into the economy and raise aggregate demand for goods and services, leaving us no better off in terms of spending-driven inflationary pressures. The solution, then, lies not just in growing the workforce but in raising productivity, getting more goods and services per hour of labor expended. While some predict other changes like increased work-from-home arrangements may boost productivity over the long term, productivity growth has remained stubbornly low over the past several decades.

Economics is the “dismal science” because progress in raising real incomes and increasing wealth is a pain-staking process, built on unpredictable and serendipitous developments, and filled with trap doors and feedback loops that can turn negative. These challenges mean paying people more, by itself, can neither raise real incomes nor solve our labor shortage. We need to focus on the basics: encouraging flexible working arrangements that keep workers engaged and productive longer, leveraging technology to improve productivity, engaging “hidden workers” to grow labor supply, and improving skill levels across the board so that the amazing American jobs machine continues to work its rising-living standards magic.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.