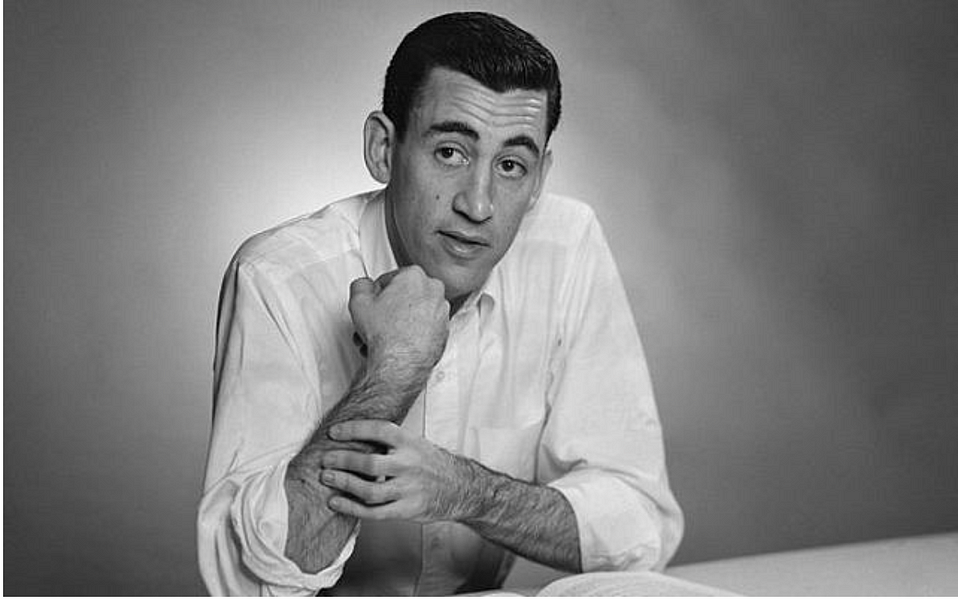

At a time when the Black Lives Matter movement has drawn new attention to the racism—implicit and explicit—in American culture, there’s a neglected J.D. Salinger short story that deserves a fresh look. Set in World War II, far from the world of The Catcher in the Rye, the story, “Blue Melody,” reveals a Salinger who saw American racism as systemic and used his status as a veteran to attack it.

“Blue Melody” (which you can read here) shows a side of Salinger most of his readers don’t know and lets us see him as far more engaged with the social issues of postwar America than he has been credited with. But “Blue Melody” is important in another way as well. It illustrates how the ongoing reassessment of America’s artists and writers in terms of their past portrayals of race need not be dominated by negative discoveries.

It is no surprise that, in the wake of his World War II encounter with the Nazi death camps, Salinger wrote about both the Holocaust (in his 1948 short story, “A Girl I Knew”) and anti-Semitism (in his 1949 short story, “Down by the Dinghy”). Salinger’s daughter, Margaret, in her memoir about her father, Dream Catcher, remembers him once telling her, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose entirely, no matter how long you live.” What Salinger’s biography does not prepare us for is his critique of racism in “Blue Melody.”

Published in 1948, “Blue Melody,” which Salinger originally titled “Needle on a Scratchy Phonograph Record,” is based on an encounter that an unnamed G.I. narrator, who like Salinger is a veteran, has with an Army doctor as they are headed to the front lines in winter 1944. The narrator tells us a little about himself. He lets us know that he belongs to an infantry division commanded by a brigadier general who seldom stepped into his command car without wearing a luger and having a photographer nearby, but that is the end of the narrator’s self-revelation. He is not interested in airing his gripes. The focus of “Blue Melody” quickly switches to the doctor the narrator has just met. The doctor, who is known only by his first name, Rudford, tells the narrator how in 1927 he and his childhood girlfriend, Peggy Moore, both of them white, became friends with Black Charles, a piano player, and his niece, Lida Louise Jones, a blues singer, in their hometown of Agersburg, Tennessee.

Rudford and Peggy idolize Black Charles and Lida Louise, and they are in turn treated with great kindness. As Rudford says of Black Charles, “He was something else—something few white players are. He was kind and interested when young people came up to the piano to ask him to play something or just to talk to him. He looked at you. He listened.”

The first half of “Blue Melody” has an idyllic quality to it, despite its Jim Crow setting. There is a gentleness to Salinger’s tale that is not present in Eudora Welty’s 1941 short story, “Powerhouse,” her moving tribute to the musician Fats Waller during a time of racial bigotry.

In “Blue Melody” the racial idyll ends without warning. In the middle of a picnic, Lida Louise’s appendix bursts. Rudford, Black Charles, and Peggy rush Lida Louise to the nearest local hospital, but she is turned away. “I’m sorry but the rules of the hospital do not permit Negro patients,” they are told. The answer has an eerie parallel to the claim of following orders that so many Nazi officials made when they were confronted with their war crimes. Salinger was, as his biographer Kenneth Slawenski has noted, bringing the Holocaust home to post-World War II America.

A similar rejection occurs at a second local hospital that Lida Louise is taken to, and before she can be driven to Memphis for an operation, she dies in the back seat of the car Black Charles is driving. Her death calls to mind that of blues-singer Bessie Smith—the subject of Edward Albee’s 1959 play, The Death of Bessie Smith, which is based on the now discredited legend that in 1937 Smith bled to death when a whites-only hospital in Mississippi refused to admit her following a car accident.

Lida Louise’s head was in Rudford’s lap when she died. For Rudford, Black Charles, and Peggy, Lida Louise’s death is a tragedy. Rudford and Peggy both attend Lida Louise’s funeral. Then the story jumps ahead 15 years to 1942 and a chance meeting in New York between Rudford and Peggy, who is now married. They are glad to see each other, but all they can talk about is Lida Louise and a record she made that Rudford still owns.

Shortly after this point, “Blue Melody” ends. The chance meeting between Rudford and Peggy does not spark a romance, but what makes the story different, especially for Salinger, is that politics, rather than plot and character shape its conclusion. Much earlier Salinger made his intentions clear when he had his narrator warn the reader not to think the story was a “slam” against one section of the country. “It’s just a simple story of mom’s apple pie, ice cold beer, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Lux Theater of the Air—the things we fought for in short. You can’t miss it really,” the narrator had insisted with an irony that today seems overdone.

But in 1948—the year President Harry Truman ordered the Army desegregated—there were plenty of reasons for readers not to see the irony of “Blue Melody” as overdone. Three years after Germany’s and Japan’s surrender, the indictment Salinger was leveling against America for its failure to live up to the values for which it had fought World War II was one that few mainstream novelists or politicians were willing to make.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.