Earlier this month, to commemorate . . . well, it’s not clear what, The Atlantic released a list of 136 great American novels of the past 100 years. A brief introductory essay explains that the magazine sought to establish the “new American canon” by identifying “novels that say something intriguing about the world and do it distinctively, in intentional, artful prose.” In the process, the list-makers wanted to “single out those classics that stand the test of time” while also drawing attention to “the unexpected, the unfairly forgotten, and the recently published works that already feel indelible. We aimed for comprehensiveness, rigor, and open-mindedness.”

You’ll find plenty of the usual suspects rounded up here, including The Great Gatsby and Invisible Man, The Catcher in the Rye and Catch-22, The Sound and the Fury and Slaughterhouse-Five, Beloved and Underworld. If you keep up with contemporary fiction, you won’t be surprised to see authors like Lauren Groff, Percival Everett, and Jonathan Franzen. You may even like that the list-makers’ open-mindedness encompasses three children’s novels and three graphic novels, or that novels from the past 25 years compose almost a third of the list.

There are, however, many glaring omissions. Neither Tom nor Thomas Wolfe was invited. William Styron and Wallace Stegner, once regulars on lists like this, are on the outside looking in. Ernest Hemingway and John Updike both appear only once. Ditto Saul Bellow, the only author to win the National Book Award three times.

Dead white men—reliably culled during canonical and curricular revisions—are by no means an endangered species in The Atlantic’s list. William Faulkner and Philip Roth both have two works included, for example. But it’s clear that one purpose of the list was to, in progressive parlance, decolonize the canon. The marginalized move toward the center of the page; the subaltern approaches superiority. Toni Morrison stands alone as the only author with three novels selected.

Meanwhile, the many obscure novels by less famous authors are often praised primarily for their focus on social justice and identity politics. One work, we are told, “delivers a powerful indictment of racism, sexism, and the class system in America.” Another depicts “the ongoing racist violence that characterizes . . . life as migrant farmworkers in California’s Central Valley.” Yet another asks, “What does it mean to betray your race?” And still another “makes the powerful argument that for Black activists, especially female ones, there can be no justice without wellness.”

As for LGBTQ2S+ fiction, one novelist explores the “complex transgender and gender-diverse identities not broadly represented in the mainstream.” Another, set in “the queer carnival of disco clubs and bathhouses that flourished in New York City between the Stonewall uprising in 1969 and the onset of the AIDS crisis in the early 1980s,” features a character who offers advice the recommender assures us “still holds true … ‘For heaven’s sake, don’t take it so seriously! Just repeat after me: “My face seats five, my honeypot’s on fire”.’” As George Will might say, Well.

The revisionist impulse behind this project becomes especially clear when you compare the list to another attempt at canonization from just a couple of decades ago. In 2005, the New York Times asked writers, editors, and others in the know to name “the single best work of American fiction published in the last 25 years.” There is some overlap between that list and the latest. Toni Morrison’s Beloved was the winner. Don DeLillo’s Underworld and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian were runners-up. But 15 of the 22 books that received multiple votes 20 years ago are absent from The Atlantic’s list. And compared to the more recent list, the Times’ would never pass muster today. Morrison and Marilynne Robinson were the only women there; Edward P. Jones (absent from The Atlantic’s list) and Morrison were the only writers who weren’t white.

In an essay prefacing the Times’ list, A.O. Scott acknowledged a certain amount of uniformity to the selections. Many of the novels were nostalgic stories set on the East Coast. Many of the novelists were born in the 1930s. But he offered no apologies because the novels were selected by more than 100 “prominent writers, critics, editors and other literary sages,” and the Times tallied up all the novels receiving multiple votes. Not an infallible process nor a perfect final product by any means, but the list’s democratic component makes its elitism more trustworthy.

The process for The Atlantic’s list seems notably less transparent. The introductory paragraphs inform us only that the magazine solicited suggestions from experts and then winnowed those down. But if the process isn’t transparent, the purpose is: to include as many previously slighted demographic categories—Asian (Vietnamese, Korean, Indian), Native American, Latino, gay, transgender, black—as possible. It’s hard to avoid the impression that the editors feared excluding any category for fear of giving offense, resulting in the unwieldy number of 136 novels.

Obviously, and this bears repeating, the point is not that the canon should be the exclusive domain of white men. Nor is it that literary tastes should be set in amber. The literary canon is in flux, and it’s likely that some overlooked works—no doubt including a number written by minority writers—are worth recovering. That was certainly true of Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, which had been forgotten between the Harlem Renaissance and the 1970s before gradually becoming a staple. It was also true of Richard Yates’ Revolutionary Road, a 1961 novel that was generally ignored until it was widely celebrated in the early 2000s (but which is absent from The Atlantic’s list). Nonetheless, we should be skeptical of the particular fluidity of this new canon because it so clearly centers identity and representation as criteria for reconsideration.

In his 1993 book Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation, the literary scholar John Guillory observed that the canon debate was “preeminently an expression of identity politics.” That remains true, though where Guillory then referred to “the telegraphic invocation of race/class/gender,” it’s clear that sexual orientation has displaced the middle category. Apart from the identity politics involved, it’s reasonable to expect that as America becomes more diverse its pantheon of great novelists will include more people of different backgrounds and identities. Readers should welcome that. The danger is that the cultural critics and university professors who shape the canon lose sight of the many traits inherent in the novel as an artform—the quality of its writing, the adherence to or subversion of generic conventions, the depth (and breadth) of its characters, the variety of ideas and themes it can explore—when they emphasize these demographic categories and social justice concerns instead.

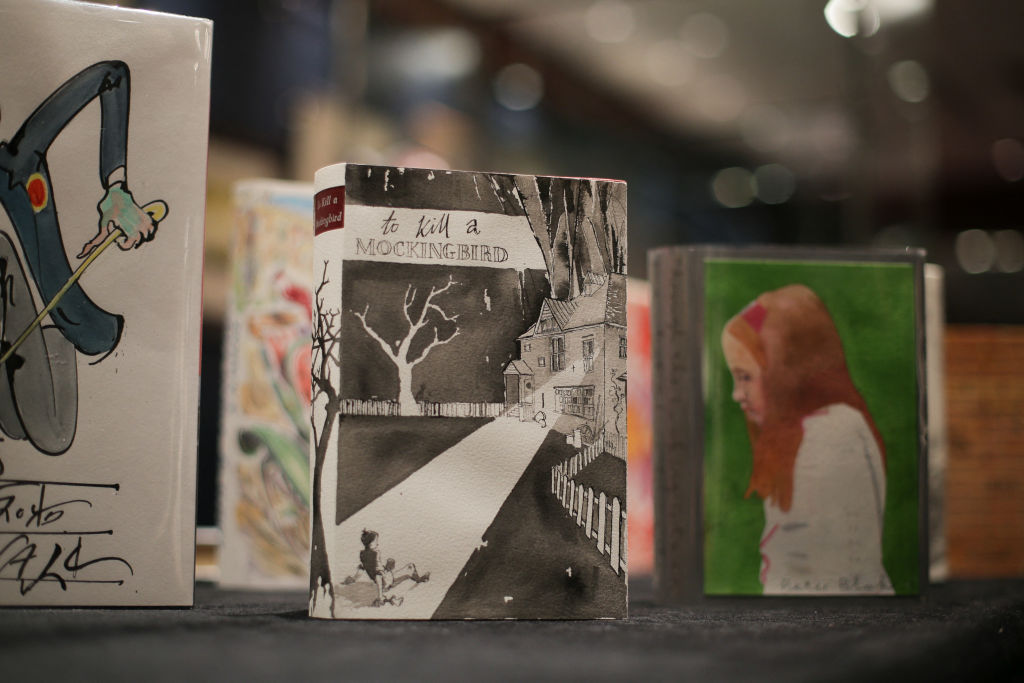

Such a process will include its own ironic omissions. The Atlantic’s list portentously reminds us that these days, “the novel is … under threat, as the forces of anti-intellectualism and authoritarianism seek to ban books and curtail freedom of expression.” They proudly announce that they’ve included at least 60 works that “have been banned by schools or libraries.” Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, a novel that has recently been attacked by progressives for its depiction of race, is not among them.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.