Dear Republican senators,

I will not try to convince you how to vote in the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump. I won’t even lecture you about the need for witnesses, in part because by the time you see this it will probably be too late. My request is far more humble and possibly far more consequential: When you vote to acquit Trump of the charges leveled against him, please, please, forthrightly reject the central argument of Trump attorney Alan Dershowitz.

According to Dershowitz, “abuse of power” is not an impeachable act. Seriously. Any abuse of power that doesn’t include a separate violation of criminal law is immune from impeachment, he contends. Indeed, any act—whether you call it abuse of power or corruption—is, for Dershowitz, fully within the president’s constitutional ambit.

So a president who gets fall-down drunk every day and fails to fulfill the barest minimum of his duties cannot be impeached because getting drunk isn’t a crime. Do you want to validate that nonsense?

I’m not picking that hypothetical out of the ether. During the Senate’s Q&A session Wednesday night, Dershowitz told you the Senate’s impeachment power over federal judges is different than that over presidents. Judges can be removed from the bench for violating the standard of “good behavior.” So, Dershowitz conceded, if a judge gets falling-down drunk on the job, the Senate can remove him.

It would be hard to argue otherwise, given that the first impeachment trial held by the Senate removed judge John Pickering from the bench in 1803. The primary charge was that he was “a man of loose morals and intemperate habits” who at least once was drunk on the job.

But, Dershowitz argued, the president doesn’t serve only during “good behavior” because he is answerable to the voters.

It’s an interesting distinction. The only problem: There’s nothing in the Constitution to back him up. There’s also nothing in the Constitution (or the Federalist Papers) to support the idea that so long as the president doesn’t violate criminal law, he can’t be impeached.

The standard response to this is: “What about the phrase ‘high crimes and misdemeanors’ in the Constitution?” The problem here, as most constitutional scholars will tell you, is that “high crimes” doesn’t just mean “violations of federal law.” It would be weird if it did, given that when the Constitution was ratified there were no federal crimes, save for those mentioned in the Constitution (bribery, treason, and piracy).

Alexander Hamilton, writing in Federalist 65, explained that high crimes “are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust.” Presumably, refusing to attend meetings, sign legislation, or conduct foreign policy because you were too busy doing keg stands in the Rose Garden would be a violation of the public trust.

Again, Dershowitz is almost completely alone among legal scholars alive today in making this argument. But he is not alone historically.

Dershowitz cites the legal arguments of Benjamin Curtis as a controlling precedent. Curtis was President Andrew Johnson’s lawyer during his 1868 impeachment trial. Like Dershowitz, Curtis argued that mere abuse of power wasn’t enough for a president to be impeached. The president needed to seriously violate the law.

Johnson avoided removal by one vote—and Yale law professor Bruce Ackerman persuasively argues that the one vote was secured at the last minute not through the power of Curtis’ arguments but by naked bribery.

Regardless, because Johnson survived impeachment, Dershowitz has a lawyerly point. Curtis “won,” so maybe his argument has precedential power after all.

If—and I should probably say “when”—you acquit the president, this precedent will gain even more power. And it is a terrible, dangerous, ridiculous precedent.

The president’s strategy of completely stonewalling an impeachment inquiry has damaged congressional authority enough. There’s no fixing the damage of that precedent now. But validating Dershowitz’s claims would take a sledgehammer to the checks and balances at the heart of the impeachment power. Lending credence to the idea that presidents can literally do anything they want so long as they don’t violate federal law (including promising pardons to induce henchmen to commit crimes for them—an act James Madison considered impeachable) would cover this Senate with shame.

Republican senators, I understand that you think it’s necessary to acquit President Trump. Fine. The least you could do is offer a resolution stating that Dershowitz’s argument isn’t the reason for your decision.

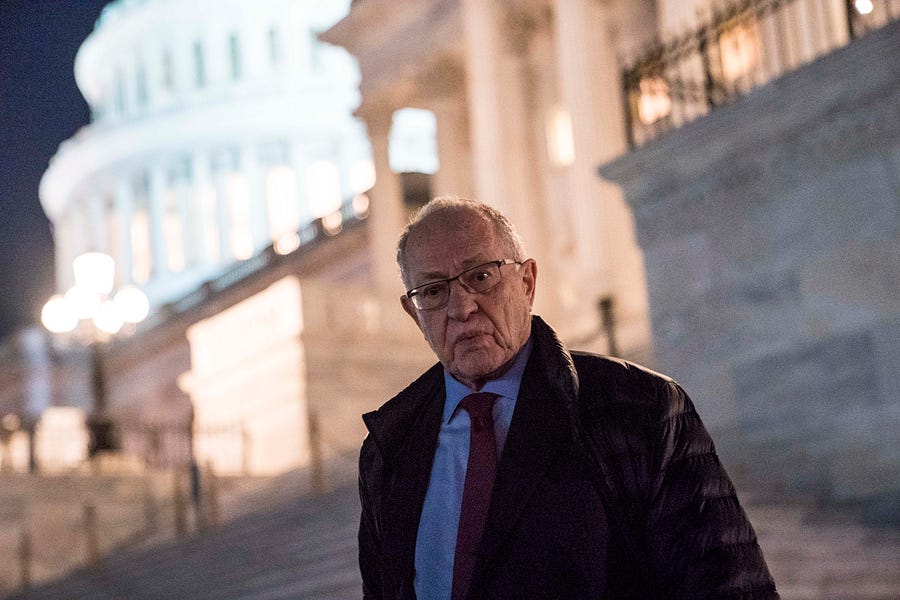

Photograph of Alan Dershowitz by Sarah Silbiger/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.