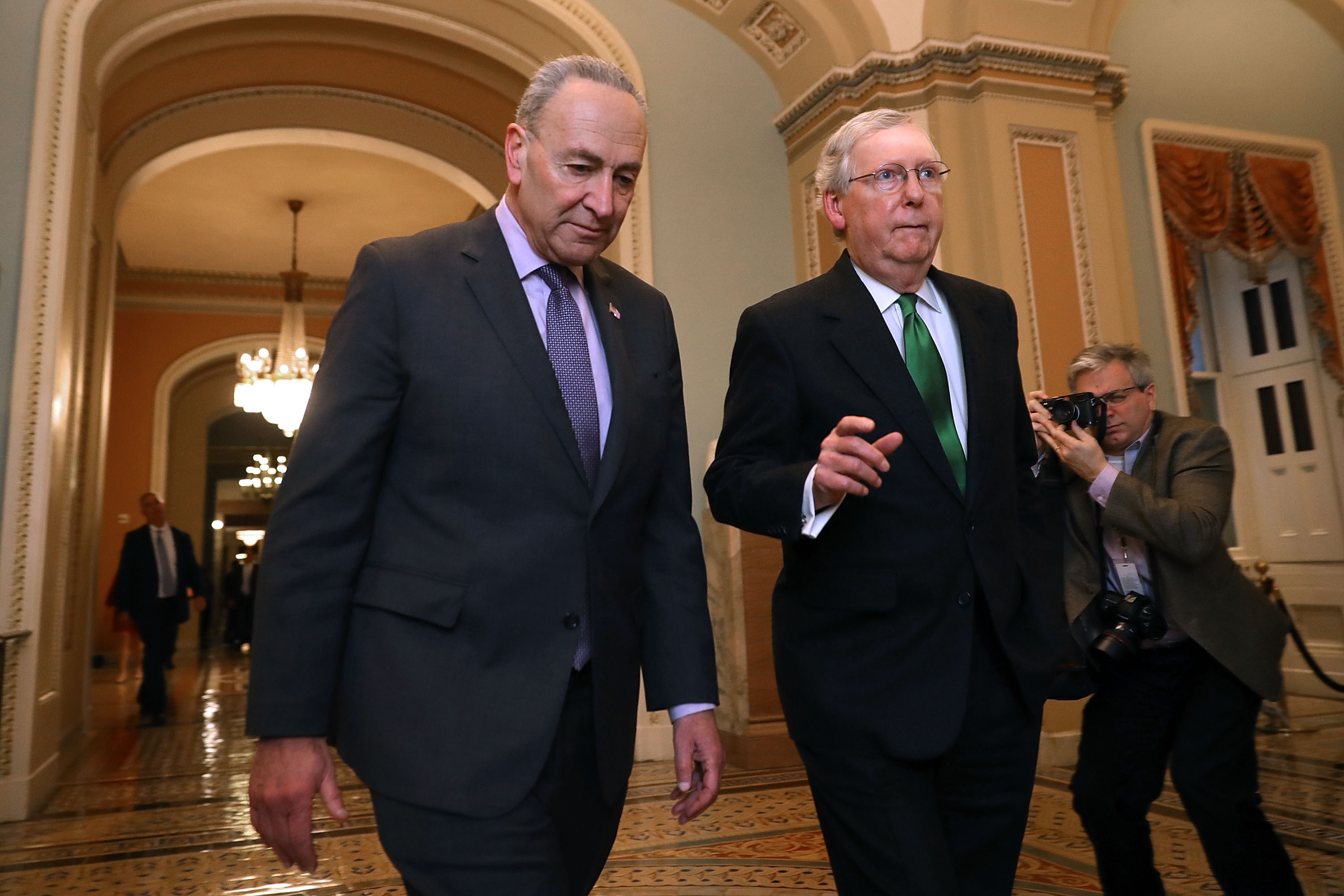

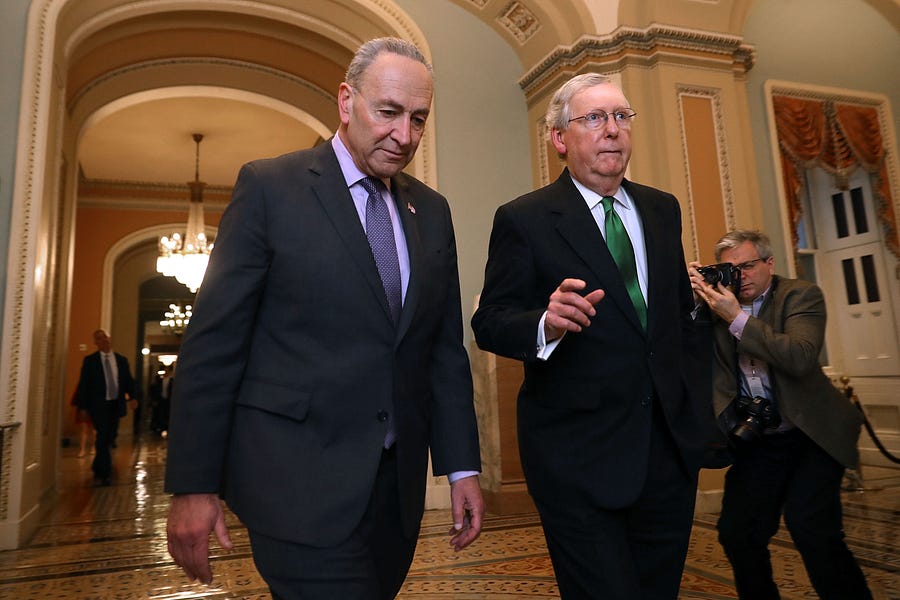

The Senate’s power-sharing agreement, key to proceeding with the Biden Administration’s agenda, has finally been resolved after Mitch McConnell dropped his demand for a guarantee that Chuck Schumer won’t scrap the legislative filibuster.

Schumer knows the benefits to his caucus that come with the threat of eliminating the filibuster, and many prominent Democrats have called for the legislative filibuster go the way of the judicial filibuster, which was partially eliminated in 2013 by Democratic Sen. Harry Reid and then eliminated entirely in 2017 by McConnell.

Completely eliminating the legislative filibuster is a shortsighted policy that overlooks legitimate concerns about a majority party becoming a legislative steamroller, passing seismic bills on thin majorities in a sharply divided country.

Indeed, although the filibuster may have originated as an accident and was used routinely by Southern segregationists, the fact remains that a bipartisan group of 61 senators signed a letter in 2017 defending the filibuster as an important tool to preserve deliberation on legislation moving forward.

Rather than eliminating it altogether, Senate leadership should pursue filibuster reform. Such reform can take many shapes, but they all should rest on a simple principle: Instead of allowing the filibuster to be used always or never, let it be used sometimes and selectively.

The concept is straightforward: Cap the number of times a legislative filibuster can be invoked throughout a congressional term. Once that threshold has been reached, the chamber proceeds in pure majoritarian fashion.

Limiting the filibuster in this manner would force the minority bloc to recognize and articulate its truly important priorities while defending Senate affairs from the indiscriminate use of the filibuster. Perhaps a sliding scale is warranted—the larger the minority, the more times it could use the filibuster.

The mechanics of this reform can be worked out, but the practice of stymying legislation simply because it’s politically feasible should become an artifact of the polarized era elected officials hope to transcend. We should recognize the haphazard and obsessive use of the filibuster for what it truly is: anti-democratic.

We’ve seen how the filibuster can be a tool of bad-faith obstructionism, turning the world’s greatest deliberative body into a legislative graveyard where the minority can paralyze the progress for which a majority of the country has voted. As Alexander Hamilton observed in 1787 when commenting on a minority’s ability to impede a majority by requiring a supermajority to pass legislation, “what at first sight may seem a remedy, is, in reality, a poison.”

However, when rightly devised, the filibuster can be an instrument of good-faith governance, ensuring that—on the most contested issues of the day—narrow majorities cannot re-engineer society without consent from at least a portion of the minority. Such support also confers greater legitimacy to the resulting legislation by making it harder to mobilize an entire party’s campaign against it in a subsequent election while avoiding the cyclical, fickle whims of the majority.

Senate leadership can meet in the middle by protecting the need for broad consensus on the handful of issues most important to the minority while allowing the Senate to carry out its business for everything else.

Americans should be concerned when one branch of the government’s internal processes leave it wholly incapable of participating in governance. Hindering legislative action on commonplace functions is an exercise of raw political power that should have no place in a republic. It’s little wonder that executive power and administrative agencies are ascendant, political parties are weak, and the general public is frustrated with legislators who have no incentive to do anything but performative grandstanding because their institution is incapable of fulfilling its constitutional role.

Abolishing the filibuster outright would exacerbate the same structural dynamics that fuel the discontent we all feel so acutely. And it would almost certainly raise the stakes of every election by sentencing the minority to irrelevance and erasing any incentive for constructive bipartisanship.

But limiting the filibuster’s use to a few key issues each term could force honest conversations about what policies matter most and, in so doing, reorient our politics toward the checks and balances that encourage everyone to come to the table and have a stake in the outcome.

We could return to politics that, as Joe Biden said in his inaugural address, leads us to “join forces, stop the shouting, and lower the temperature.” That is the type of unity to which we should aspire, and filibuster reform is an important step toward just that.

Scott S. Boddery is an assistant professor of political science and public law at Gettysburg College and is an expert in judicial politics, court legitimacy, and institutional design.

Benjamin R. Pontz is a Fulbright postgraduate scholar at the University of Manchester where he researches governance and public policy in the context of institutional legitimacy.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.