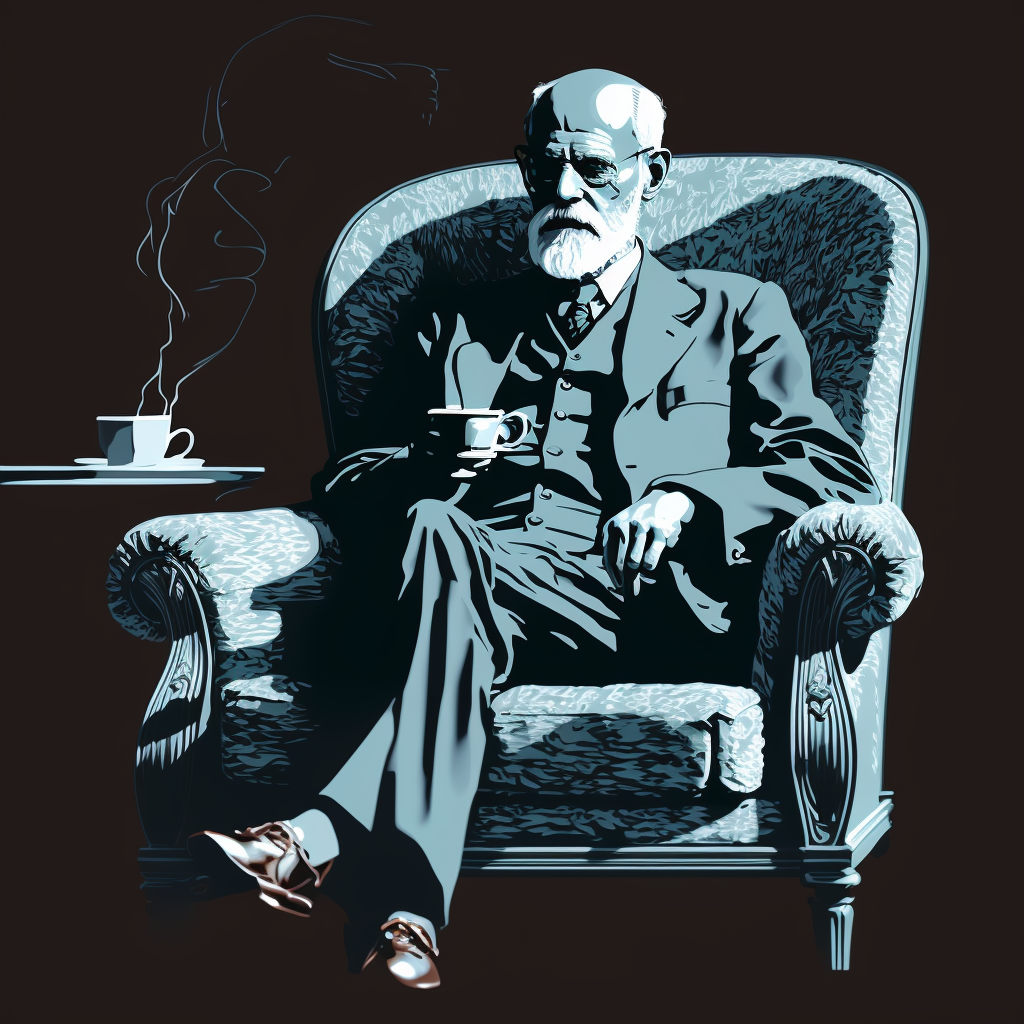

I am not much for taking selfies. My lifetime total is probably still in the single digits. But buried deep in the cloud, dated May 22, 2013, is one I rather like. It is a picture of myself reflected back from a smallish wall mirror, hanging not on a wall, but in the middle of a window, suspended from its handle. The window is located at Berggasse 19, Vienna, the apartment where Sigmund Freud lived and worked for almost 50 years.

I have always thought there was something just a bit uncanny—to borrow a word about which Freud himself wrote an important essay—about staring back at myself out of the same mirror from which Freud stared back at himself many years earlier. It’s as though the two of our subconscious selves were in there together, behind the glass, trying to get out.

Berggasse 19 is now a museum commemorating Freud’s life and work. Its chief appeal—although I have not seen it since it underwent renovation and expansion a few years ago—is, like that mirror, the sense of Freud’s presence. Few of his actual belongings are there, but one senses his spirit presiding over the premises where so much of his important work was done.

His belongings are missing because he took them along when he fled Vienna in 1938—reluctantly and under intense pressure from friends—in order to escape the Nazis. After difficult negotiations with the occupying Germans, and with help from the American government and financial support from Princess Marie Bonaparte, Freud finally reached London and took up residence at his new address, 20 Maresfield Gardens. Already seriously ill from long-term cancer of the jaw, a result of his habitual cigar-smoking, Freud lived only about a year at his new home before dying in September 1939.

It was at 20 Maresfield Gardens, now also a Freud Museum, that I recently had Kaffee und Kuchen, coffee and cake, with Herr Doktor Freud—not in person, of course, but as genius loci of his final address, much as I had earlier encountered his spirit peering out of that old mirror in Vienna. Just as I was preparing for a short trip to London, an email came through my inbox inviting me to register for this special event. Normally I would have ignored it, but in this case the timing was perfect. I couldn’t resist.

I thus found myself, just over a week ago, seated in Freud’s former London dining room. Along with about 20 other guests I enjoyed authentic Viennese apple strudel from the London chain Kipferl, along with coffee brewed by museum staff, all served on fine bone china decorated with a Jugendstil image of Oedipus and the sphinx, taken from Freud’s own Ex Libris. After a welcome from Giuseppe Albano, director of the museum, we heard a brief presentation on the Viennese coffee house—one of the great cultural institutions of Western civilization, recognized as such by UNESCO’s inventory of the world’s intangible cultural heritage—from events manager and art historian Jamie Ruers. We then all marched together into the study to watch curator Marina Maniadaki point out some of the antiquities from Freud’s extensive collection, including a small statue of Athena, his favorite, which he smuggled into London while still uncertain whether the rest of his belongings would successfully follow.

Afterwards we were ushered upstairs as the first guests to see the museum’s modest new exhibition on “Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire.” Freud often used archaeology as a metaphor for his own psychoanalytic technique; in his essay “Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva,” for instance, he writes, “There is, in fact, no better analogy for repression, by which something in the mind is at once made inaccessible and preserved, than burial of the sort to which Pompeii fell a victim and from which it could emerge once more through the work of spades.” Although the museum’s exhibition space is quite limited, the new show offers a nice selection of artifacts from Freud’s collection, curated to illustrate some of his central preoccupations, ranging from the role of dreams, to the significance of myths like the story of Oedipus, to the origin and psychological meaning of religion. The small exhibition is accompanied by a digital archive that may be of interest to those for whom London is an unrealistic destination.

Inevitably, however, the visitor to Maresfield Gardens is drawn back downstairs to the study. I’m not sure I have ever encountered another room that so palpably exuded the personality of its resident. By the wishes of Freud’s daughter Anna, an important child psychologist in her own right, who lived in the house for another 40 years after her father’s death, the room has been left precisely as Freud knew it. From the elegant dark-wood furniture to the bookshelves lining the walls and filled with volumes of philosophy, literature, history, medicine, and more, Freud’s study breathes an atmosphere of both comfort and contemplative intensity. In my experience, visitors consistently fall silent upon entering, talking in whispers, as if this were a kind of sacred space. The walls are covered with art, often depicting mythological or other scenes related to Freud’s work, and it contains several vitrines displaying his collection of statuettes, busts, amulets, and other links to the ancient past. Sixty-five of his favorite antiquities adorn his large desk, where he could contemplate them as he worked, picking up different objects and drawing inspiration from this tactile contact with earlier stages of human consciousness.

The room’s centerpiece, of course, is “the couch,” made famous by every New Yorker cartoon featuring a psychiatrist ever published. Placed along a wall not far from Freud’s desk and covered by a large oriental rug, it immediately draws the viewer’s eye upon entering. While his patients lay on the couch, undergoing the “talking cure,” Freud sat at their head, taking notes just out of sight—although, as Maniadaki pointed, a patient who looked up would find, directly in his line of sight, a bust of Freud atop a pedestal, so that the master, like a repressed memory, remained present even when absent. Because of his advanced illness, Freud saw few patients after arriving in London—only four, we were told by Albano—but as one stands in this room, it is not hard to imagine lying down upon that couch and beginning to relate that strange dream one had last night.

Freud remains a challenging figure. My students, overwhelmingly evangelical, are almost universally resistant to encountering him. I like to joke that he is one of two important thinkers—Darwin is the other—whose work they have never read but know is wrong. Recognizing that even upon a thoughtful reading they will ultimately disagree with much of what they find in Freud, I encourage them to risk a more open engagement. Freud’s central teaching is one with which any Christian can agree and that should be familiar to any reader of St. Augustine’s Confessions: that we never truly know ourselves very well. More: that as we strive to know ourselves better, we will often find, if we are honest, that the deeper we dig, the less we like what we discover. I always suspect that Freud may have taken just a bit too much pleasure in reminding us of this. But he was not mistaken.

Should you happen to find yourself in London, the museum is worth a visit. And check out its calendar of upcoming events for a possible Kaffee und Kuchen gathering. I was told by museum staff that they used to hold such events regularly, although this was the first time they had done so since the coronavirus pandemic. They seemed encouraged by last week’s success, so one hopes they will restore the practice on an ongoing basis. After all, who would not want to spend a morning having coffee with the intriguing Dr. Freud?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.