Eliot Cohen—a military historian, former diplomat, academic dean, and Washington policymaker for more than 30 years—once saw a production of Henry VIII at the Folger Theater in Washington, D.C. In the course of that play, Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s chancellor, bids a painful farewell to his greatness. Cohen recognized in Wolsey’s fall from power a common passage in the nation’s capital, and he decided to write a book about traversing “the arc of power.”

The end result is The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall, a book that will appeal to anyone who recognizes in Shakespeare’s casts of characters our common, complex humanity, necessarily political but not consummately so, usually not happily political, and not ever one-sidedly political, either. All the shades of ethical color intermingle in Shakespeare’s power-plotted characters, just as they do in us, with good and evil, genius and foolishness, beauty and ugliness, all inextricably embodied.

Why Shakespeare? Why not a personal memoir or biography of some exemplary leader who traversed the arc of power? The answer, Cohen reminds us, is that Shakespeare studied power up close in the courts of kings and queens and in the posthumous company of authors we still read or don’t read, under the scrutiny of the most versatile and acute imagination and verbal prowess ever possessed. Shakespeare took power seriously, theatrically, humanly, yet not as the be-all and end-all of human life. He was always conscious of the end, for plays must be made to end, and though characters may live forever on stage, human beings, whether kings or slaves, do not.

Cohen makes us see and feel, especially at the end of the arc, the things that are more important than power—in Shakespeare’s world as in ours—across all genres and historical periods. King Lear discovers these things in agony; Prospero, in peace of mind; Nixon, in despair; Caesar, in delusional surprise; and Barack Obama in the aftermath of a magic that filled the world with hopes, but not their deeds.

In the three parts of The Hollow Crown—acquiring power, exercising power, and losing power—Cohen makes numerous links within the Bard’s catalog of plays and applications to modernity, many of which are surprising and illuminating. In Coriolanus’ tragic story, he sees an image of Benedict Arnold, the great revolutionary soldier turned traitor (as Coriolanus became traitor to Rome) from “outraged pride” and offended honor, from boyish fragility in the face of felt ingratitude. Lincoln acquires and exercises power as Bolingbroke (Henry IV) does, with an uncanny ability to disguise his ambition and ruthlessness. If only Arnold and Coriolanus had Lincoln or Bolingbroke’s melancholic realism toward the contemptible in man—better than to be regarded as the hateful. For when hate takes over from contempt, as Cohen quotes Nixon’s farewell speech to his White House staff, then “you destroy yourself.”

Cohen also explores Hal’s tutelage under Falstaff and the tavern in the Henry IV plays. It’s there that the future Henry V learns the common touch that he will need to unite the fractious Britons and persuade them to die for what Falstaff knows is nothing but a word: “honor.” And here Cohen deepens our familiarity with Hal, a trainee in the acquisition of power. Hal must learn about that “nothing” to fashion it into a “something” that even he, the “master manipulator,” will believe, in the moments of utterance before Agincourt.

A chief virtue of The Hollow Crown is its appreciation of such composition of opposites in one person. This is an essentially theatrical insight: that character is multiform. The best political actors are double or triple selves, whereas the worst, like Coriolanus, cannot and will not escape their single selfhood. Thus, on the one hand, Hal and Falstaff are true friends; at the same time, Hal and Falstaff use each other, with cold calculation on Hal’s part, and warm presumption on Falstaff’s. Cohen unfolds this deep understanding of character—as containing opposites, not simply alternating in time and place, but co-present—throughout his book.

Cohen also shows how Shakespeare understood the intricate reasoning of conspirators, whose motives for literal or metaphorical assassinations they often hide even from themselves. This seemed to be the case, Cohen suggests, with Mark Felt, the “Deep Throat” of Watergate fame. Likewise, only complex motives make a man want to occupy center stage continually. Take Julius Caesar. Caesar cues his own assassination by proclaiming himself before the Senate to be like the North Star, fixed and eternal. Cohen sees this Caesar as possessing “a monstrous ego,” which refers to itself in the third person, “intoxicated” with self-regard and power. But he fails to consider that Caesar, by speaking this way, is effecting his own transformation into “Caesarism,” which requires his slaughter and subsequent institutionalization under the cleanly efficient Octavius. His assassination is political theater, and Caesar himself is a sacrificial player.

The winners in the assassination act it out according to the theatrical dictum that those who live to please must please to live. Cohen sees clearly how poorly Brutus pleases the audience of Romans by trying to impress them with his honorableness and his bloody-armed proclamation of “peace, freedom, liberty.” Antony, on the other hand, knows that the mob will be pleased by the presence of Caesar’s body as a prop, whose stabbings Antony, by consummate poetic rhetoric, will make them imagine in as lively a manner as we’ve just witnessed. And as for slogans, maybe the mob is right: Who cares for peace, freedom, and liberty if friends must kill friends to obtain them?

Cohen does miss an opportunity in his discussion of Caesar, Cassius, Brutus, and Antony, for he doesn’t go on to consider the power lessons of Antony and Cleopatra. Love may matter more than Rome, if the words that give love expression convince us that this is so. But do such words dupe us, as Falstaff says his contemporaries are fooled by the words of “honor”? Is the language of love, nowhere greater than in Antony and Cleopatra, merely air? How many leaders does Cohen know who, like Antony, have turned from Rome and power for the sake of their heart strings?

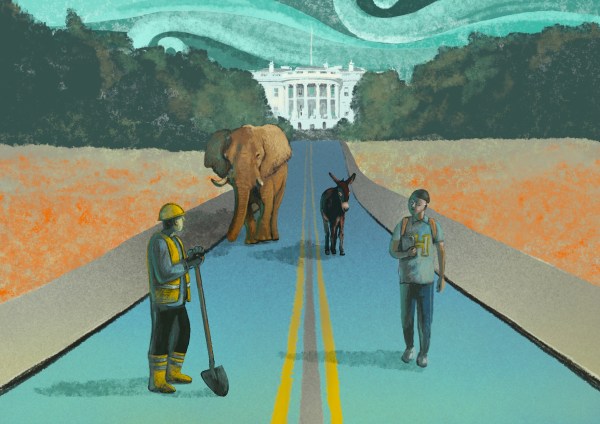

The greatest lesson of Macbeth, according to Cohen, is that power destroys “human bonds and sympathies.” He asks us to look into the deadening eyes of Vladimir Putin over the years to witness this process. Macbeth, whose soul is almost extinguished by the arc of power, engages in what Cohen calls “magical thinking” (as Joan of Arc and Owen Glendower do in earlier plays). Such thinking is a serious part of politics when it inspires confidence and hope. Think of Barack Obama, whose belief in himself and his rhetoric provided him with an aura of greatness that many subscribed to. But that magic did not last, as Macbeth, Joan, and Owen find out, too. The woods came to Obama’s Dunsinane in the form of the American Jack Cade, the populist businessman, Donald Trump, elected on Obama’s exit by people who had been hearing the hard, realistic word “no” to their aspirations, not the magical words, “Yes We Can.”

And in both Macbeth and Richard III, Cohen also sees the rule of Hitler, Stalin, and Xi Jinping, all made paranoid by the addictive process of killing, literally or metaphorically. Sometimes, like Richard, they become morbidly interested in the details of murder. This sets up the calculus that Macbeth best illustrates: You have to eliminate those your power has made to suffer before they eliminate you. Can Macbeth do that in time? Why not, with enough power, kill them all? Is there a reason this is not possible? Must the bad guys lose in the end? Cohen does not duck the question, but rather faces it in the last part of his book.

The reason the bad guys lose in the end—and the good guys too—is human mortality. Henry V, one of the good guys, comparatively speaking, loses because he dies unexpectedly, and his infant son becomes king. No son is ever like his father, and you’d have to be like Henry V to maintain his conquests and his hold on the warring nobles. Innocence, arrogance, and the fragility of power itself, as Margaret Thatcher discovered one day, all contribute, in Cohen’s telling, to the passing of power and the loss of its gains.

Cohen thinks it best to learn how to walk away from power and to give it to someone else to exercise for a time. Lear fails spectacularly at his attempted retirement. His aged counterpart Prospero in The Tempest, however, having learned the lesson of dehumanization by power, gives it up successfully. For the sake of his daughter and his own soul, he drowns his book and buries his staff, so that he does not continue to suffer the brutalization and coarsening he studied in himself and Caliban, whose acquisition of speech, the quintessential empowerment, taught him to curse.

The great historical counterpart to Prospero, who closes The Hollow Crown, is George Washington, who walked away because power, he knew, is not the most important thing in life. It’s not what makes us most human, happy, or free.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.