At one pivotal point in the Senate Judiciary Committee’s January 31 hearing on the sexual exploitation of children online, GOP Sen. Josh Hawley challenged Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta, to stand up, turn around, and apologize to all the parents packing the audience. Zuckerberg did—and as he turned, he was met with more than a dozen large photos held up by grieving parents of kids who had committed suicide in a bitter attempt to escape their bullying and victimization on social media.

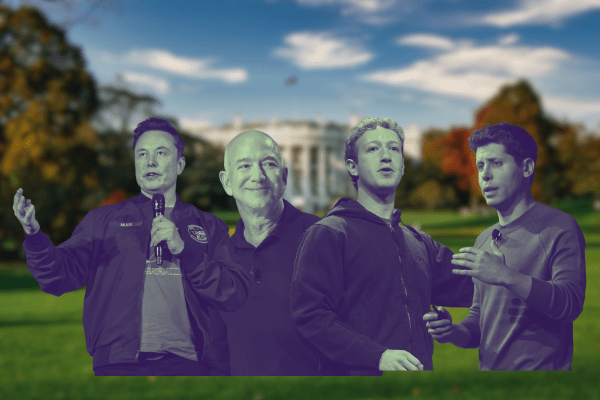

Zuckerberg had the look of a man cornered, but he wasn’t the only witness—he was flanked by the CEOs of four other social media giants: TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), Snap (the parent company of Snapchat), and Discord. And though the dramatic apology recounted above was historic, Wednesday’s hearing was far from the first time executives of Big Tech companies have been dragged in front of lawmakers, resulting in fiery clips that appear on the nightly news. The inevitable question is, will this time be any different? Will something finally be done to better regulate social media platforms for child safety? Though it would be unwise to foretell action by such a polarized Congress, the answer may very well be yes.

Last May, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy released an advisory warning that declared that current science provided “ample indicators” that social media presents a “profound risk of harm to the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents.” Murthy’s warning is supported by the research of Gallup’s Jonathan T. Rothwell, co-published by the Institute for Family Studies (IFS)—where I am the executive director—in October 2023. Rothwell surveyed 6,643 parents who care for a child between the ages of 3 and 19, as well as 1,580 of those parents’ children (ages 13 to 19), and found the following:

Teens who spend more than 5 hours a day on social media were 60% more likely to express suicidal thoughts or harm themselves, 2.8 times more likely to hold a negative view of their body, and 30% more likely to report a lot of sadness the day before.

Rothwell’s work bolsters the conclusions of scholars like Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge, who have convincingly shown that addiction to smartphones and social media have been the primary driver of a profound mental health crisis among Gen Z, which is wracked by unprecedented levels of anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide attempts.

Such findings of harm were known inside social media companies, too. On November 7, 2023, Meta whistleblower Arturo Béjar testified before a Senate subcommittee that, after rejoining the company from 2019 to 2021 to work on child safety (following a prior stint at Facebook from 2009 to 2015), he emailed Zuckerberg and other senior leadership directly to inform them that his own internal research uncovered a pattern of outrageous sexual abuse of minors on Facebook and Instagram. He testified to the following:

The initial data from the research team indicated that as many as 21.8% of 13-15 year olds said they were the target of bullying in the past seven days, 39.4% of 13-15 year old children said they had experienced negative comparison, in the past seven days, and 24.4% of 13-15 year old responded said they received unwanted advances, all in the prior seven days.

He never received a reply from Zuckerberg, and, Béjar testified, no action to clean up these specific issues was ever taken.

Unsurprisingly, given the above, a recent survey of 2,100 parents with children under 18 by Michigan State University found that the top three child health concerns of parents were overuse of devices, social media, and internet safety, respectively. This explains why, in a national survey of more than 1,000 parents that my organization released with the Ethics and Public Policy Center (EPPC) in February 2023, we found overwhelming bipartisan support for measures to make the internet safer for kids. More than 80 percent of respondents said they wanted legislation to require parental permission before a child opens a social media account, and 77 percent said they wanted full administrator-level access to what their kids are seeing and doing online.

IFS and EPPC have been credited by the New York Times with originating the policy ideas that have been translated into a host of state laws that require social media platforms and pornography sites to verify the age of their users. On the federal level, we endorse the bipartisan Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), which enjoys 46 co-sponsors in the Senate. KOSA would require social media companies to provide parents and kids with more effective tools to make the user experience more age-appropriate, such as disabling addictive product features like infinite scroll, empowering users to opt-out of algorithmic recommendations, and enabling the strongest safety settings by default. It would also impose a “duty of care” on social media platforms to make sure that they are not designing their platforms to exploit children, including by relying on algorithms that push them toward sexual exploitation material or content that promotes self-harm and suicide. If these platforms fail to live up to their obligations under KOSA, the bill provides attorneys general with the means to bring a civil action to enforce compliance and hold them accountable.

Many who hesitate to support new regulations on social media adhere to the dated view that these platforms are designed to provide individuals with fora to speak—but that’s not what they’re for. “It is important to realize that when you are online, you are the product,” GOP Sen. Marsha Blackburn recently explained in an address at the Heritage Foundation. “And [social media companies’] business models are built on your addiction.” The value of addiction to these companies is that the more a user stays on the platform, the more data she generates about herself, which the companies can then use to prime her for receptivity to highly tailored graphic advertisements. This power to tailor advertisements to individuals and keep their attention for hours on end is what puts these companies in a position to sell advertising space to third parties, i.e., to charge them for access to an audience of millions of addicted juveniles. We know from a recent lawsuit by 33 state attorneys general that Meta gives each 13 year-old user of its social media products a “lifetime value” of $270. That’s billions of dollars per cohort of 13-year-olds. According to one Harvard study, in 2022 alone, “Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube collectively derived nearly $11 billion in advertising revenue from U.S.-based users younger than 18.”

Critics of legislation aiming to make social media platforms safer for kids are indeed correct that the weight of judicial precedent has tilted against additional regulation, ever since Reno v. ACLU struck down key provisions of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. But these pro-Big-Tech rulings are weakened by outdated visions of the internet that are entirely ignorant of smartphones, social media, and the havoc they have wreaked on America’s kids. Consider Reno itself, which pontificates thusly:

The Internet is not as “invasive” as radio or television. … Communications over the Internet do not “invade” an individual’s home or appear on one’s computer screen unbidden. Users seldom encounter content by accident … [and] odds are slim that a user would come across a sexually explicit sight by accident.

This total misforecasting of the future of the internet that animated Reno—and set the tone for subsequent decisions—couldn’t be less germane to our moment. Similarly, 2004’s Ashcroft v. ACLU, which declared age verification an unconstitutional method of blocking adolescent access to pornography sites, assumed (quite incorrectly!) that “filters are more effective than age verification requirements.” It also presumed age verification to be too burdensome on adult speech. But technological progress and the everyday deployment of sophisticated kinds of encryption allow for secure and privacy-preserving verification, thus nullifying this critical factual predicate. In sum, the precedents that opponents of these bills rely upon are dramatically undermined by history and technology, and are ripe for being overturned by the Supreme Court, where the ultimate fate of these laws will be decided.

And pressure—from legislation in states around the country, a growing consensus among federal lawmakers, and, perhaps, a sense that their constitutional hand is weaker than it appears—has Big Tech companies preparing for regulation and jockeying for position to define what it will look like. Meta has taken out full-page ads in major newspapers, announcing support for measures to make their platforms safe for kids. Importantly, the ads put the onus on “app stores,” i.e., Apple and Google, to do the work of acquiring parental consent for a minor to download apps, including Meta’s own products. This is a clear sign that Meta expects new federal regulations by lawmakers—their maneuver is to try and guide the burden of that regulation elsewhere.

As for the other companies present at last week’s hearing, only days prior, Snap announced its full support for KOSA. At the hearing itself, Snap was joined by an endorsement from X, whose CEO, Linda Yaccarino, called for KOSA’s passage without reservation. As for the others assembled, TikTok’s Shou Chew and Discord’s Jason Citron expressed partial support of KOSA, and Zuckerberg said he agreed with its “basic spirit.” This puts wind in the sails of a bill that is waiting for the right moment to make it over the hump.

Libertarians on both the left and right who oppose KOSA are wise to the fact that our political moment is definitively hostile to any legislative action whatsoever. So, they are doubling their efforts to try and spike it. They may, in the end, have victory in court (though that is far from certain). But I would ask them—given the growing sentiment among Big Tech CEOs themselves that something must be done—to consider laying down their arms for the sake of America’s children, who need relief from platforms that prey upon them by design.

KOSA merely creates the conditions for a safer experience for kids on social media. As I have previously argued, Zuckerberg is in fact correct that the devices and app stores of Apple and Google—which profit off of the addiction of minors to these platforms by being their primary portals of access—need to be regulated, too; but he is wrong to think that this should absolve Meta altogether. Best of all would be legislation that liberates adolescents from these platforms by literally banning them from it entirely via age verification, just as we ban them from buying cigarettes, another addictive substance we once left unregulated. But if liberty is the ultimate goal, then safety is the right place to start. To that end, the Kids Online Safety Act should be passed by Congress without delay.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a Dispatch debate series. Last week, Jessica Melugin made the case against additional regulations to protect children online.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.