When I sat down in the dentist chair this Wednesday, I didn’t expect I’d end up in a conversation about religion. I’d hoped to get a crown cemented in and then move on, with the dentist perhaps offering me some kind of steep discount for being such a nice guy.

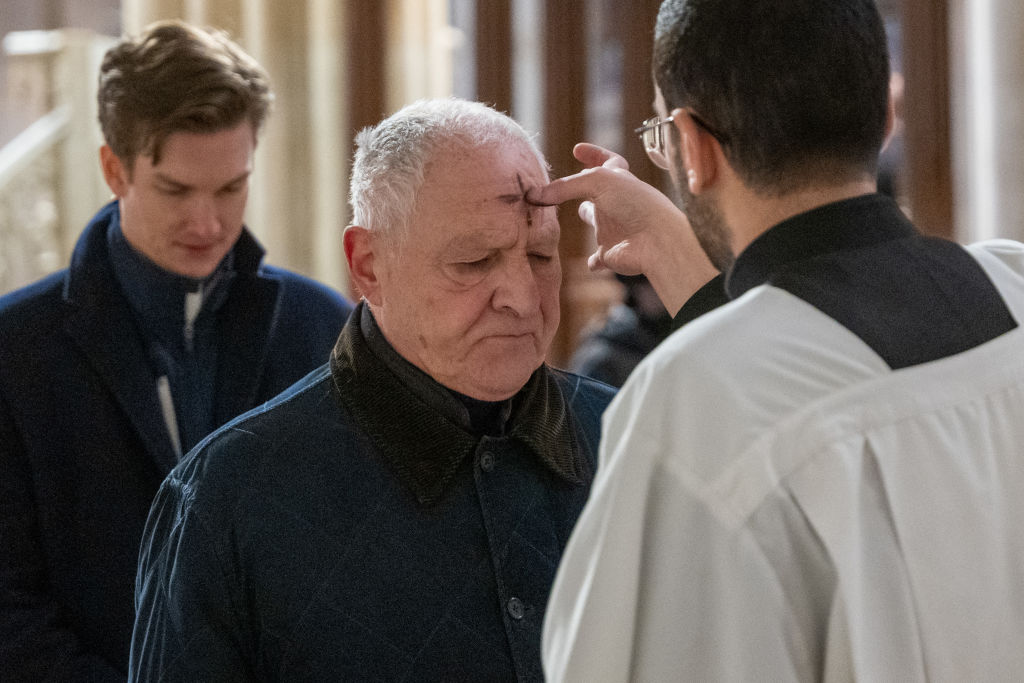

But this week was Ash Wednesday, one of Catholicism’s most recognizable and enduring holidays. So wherever I went on Wednesday, the smudged black cross on my forehead was an invitation for strangers—and dentists—to talk with me about their own religious convictions.

What I heard conformed to America’s religious trend: Like all institutional religions, Catholicism is in sharp decline in the U.S., with former Catholics making up a growing share of the American population. Americans who identify with no religion are especially on the rise.

Most people I talked with Wednesday consider themselves former Catholics, or at most the kind of Catholics who appreciate the religious formation of their youth, but who don’t make regular attendance at Sunday Mass a priority. Most of them were also enthusiastic about my ashes, however, with several keen to mention something they customarily give up for Lent, even if they don’t otherwise practice the Catholic faith. As parish priests across the U.S. will tell you, Ash Wednesday is not a day of precept—a “holy day of obligation”—for Catholics, yet it is nevertheless one of the best attended Mass days of the year.

While religion has an increasingly smaller footprint on the American landscape, Ash Wednesday remains enduringly attractive. In truth, it’s the concept most associated with Lent and Ash Wednesday—willful self-denial—that is an object of fascination for Americans.

In a decadent American culture, self-indulgence is often marketed as the surest path to self-actualization. We’ve commodified and gamified the existential human longing for meaning, with retail’s “lifestyle” segment promising that the right yoga retreat, life coach, eat-pray-love adventure tourism, augmented reality apparatus, or homestead cosplay McMansion chic will connect us both to our “inner selves,” and to something transcendent. This is what happens in a culture in which no material good is out of reach, but we don’t know the names of our neighbors, or even our grandparents, for that matter. There is some secular backlash to the consumption-as-identity zeitgeist of American culture. Consider Dry January, the “No Spend Challenge,” and, well … other made-for-social-media branded exercises in self-denial.

But it’s Lent, more than “No Nut November,” which continues to capture the imagination and attention of a largely areligious American population. And Lent is different from those secular and stoic exercises in self-denial, because the purpose of Lent isn’t actually to become master of your own domain. It is rather to acknowledge that you can’t achieve self-mastery on your own. That the Enlightenment’s promise—that we can tame nature and tame ourselves—is empty, and false. That we are creatures, not the creator, and that we find the meaning of our lives in giving ourselves away, as did—as Catholics believe—the God who came into this world, who suffered, who died, and who conquered death in his resurrection.

Boiled down, Lent asks of Catholics three things: prayer, fasting and almsgiving. Believers are asked to commit to some extra time with God, to some act of mortification or fast, and to some consistent exercise of charity for the poor.

In popular culture, it’s fasting that gets all the Lenten attention. The idea of giving up candy is both foreign and familiar, and taken alone, fasting can make Lent seem like a chance for 40 days of weight loss, or a break from doom scrolling.

But the fasting makes sense for Catholics in the context of the prayer and the almsgiving. In our family, that means putting away extra treats and most TV. It means wrangling kids into the living room for a nightly rosary. And it means making time to visit elderly people in our neighborhood, to spend time with shut-ins and sick friends. The idea is in part to cut some of the distractions, to better hear God’s voice. To deny ourselves some comfort, to be comforted by the Almighty. And to see the face of the suffering Christ in the face of the poor, the forgotten, or the alone.

Why do we do all that? Well, on a spiritual level, the idea is to find small ways to be unified with Jesus Christ, who suffered on the cross for our sins. The hope is to remember our mortality, and to take some time to consider what it means to live well.

It’s a funny thing to take 40 days each year to remember that we will die. No one likes to think about his death. And no one likes to think about the suffering he might endure before that death.

In fact, though, that might be the most important way in which Lent is a countercultural phenomenon—and hopefully a witness. If there’s a prevailing ethos of our time, it’s that suffering is bad, and to be avoided at all costs. That’s the reason MAiD promoters push euthanasia on Canadians and Europeans with even slight colds, the reason why disabled children are aborted en masse, and the reason helicopter parents go into parent teacher conferences with cold fury if any schoolteacher dares to suggest that the child eating paste in the corner isn’t a future tech bro billionaire.

Arguably, our addiction to consumer credit is built entirely around our fear of being uncomfortable. We’re scared of suffering. And we’re especially afraid to do it alone.

Lent is the Catholic reminder that suffering can be redemptive and meaningful—and that no one should do it alone. That we find ourselves—really—when we enter willingly into our own suffering, and walk gladly alongside the suffering of other people. That joy, if we dare imagine such a thing, comes from accepting that none of us is really independent, and none of us is immortal.

Happy Lent. If you’re willing, it might be a good time for a break from a creature comfort, to think about the God who created you, and to think about how you can better love the poor. And it’s a great time to remember that you will die—sooner than you think.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.