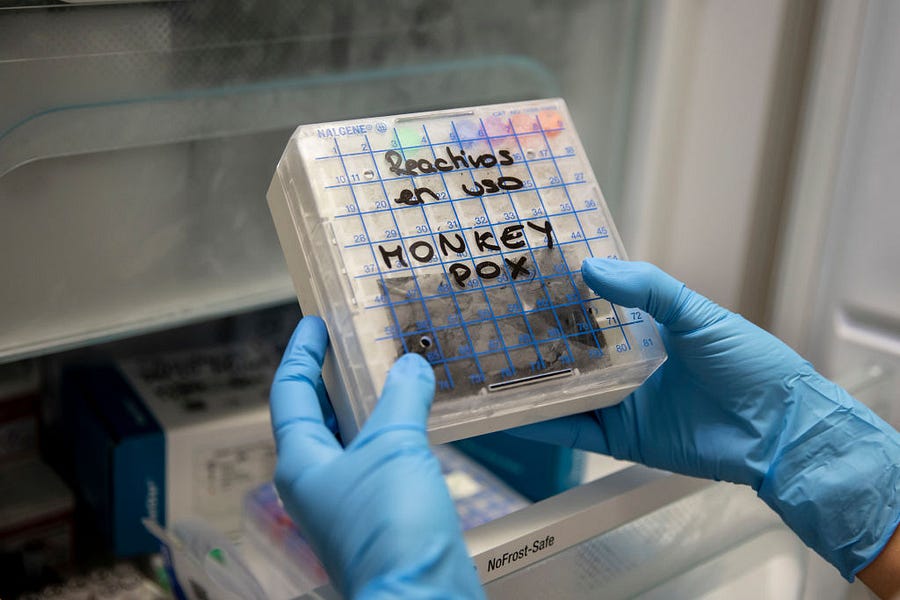

In May, alarm bells began to sound when cases of monkeypox, a virus typically found only in Africa, appeared in Europe and North America. Since then, public health authorities have confirmed more than 350 cases in half of all U.S. states and more than 5,100 cases globally. On June 1, the United States had fewer than 20 cases, with fewer than 1,000 reported cases worldwide. The seven-day average of new cases has shown a fairly linear and consistent spread of the virus as the total number of infected people grows to ever more eye-catching figures.

Aside from an ominous-sounding name (which the World Health Organization is poised to change over concerns that it incites racism and stigma), what do we know about monkeypox and the current status of the outbreak?

The virus is characterized by a skin rash that often accompanies flu-like symptoms including fever, swollen lymph nodes, and muscle aches. The vast majority of people who contract monkeypox make a full recovery, but it’s possible that pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals may be at greater risk of severe illness.

Monkeypox was first discovered in the late 1950s in West Africa in—you guessed it—monkeys, with the first human cases identified in 1970. The vast majority of cases are historically found in central and west Africa, especially the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Despite scientists having knowledge of the disease’s existence for more than half a century, “there are still a lot of unanswered questions,” said Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an epidemiologist and tropical disease specialist at the University of Toronto. Nonetheless, he added, “We’re not starting at square one.”

The U.S. has seen an outbreak once before. In 2003, the virus made the jump to humans when a 3-year-old Wisconsin girl was bitten by her pet prairie dog that had been infected by rodents imported from Ghana. Around 50 people were infected in the outbreak, and all had had some contact with infected prairie dogs, meaning there was never human-to-human spread.

The current outbreak is being driven by direct contact with infected, symptomatic people. “Most of the transmission in the past was animal-to-human,” Dr. Shon Remich, global head of Clinical Development and Operations at Takeda, a Japanese biomedical research firm, told The Dispatch. “The big concern at this particular time is that we’re seeing human-to-human transmission. Anytime a transmittable disease alters the way it gets transmitted from one host to another, it’s cause for concern.”

But there’s good news, too. According to Remich, it’s unlikely that the virus will mutate to become more contagious. Unlike COVID-19, an RNA virus, monkeypox is a DNA virus, which repairs mutations more effectively, leading to fewer new and dangerous strains.

Plus, monkeypox is not very contagious to begin with. It has a basic reproduction number of 0.5-1—that is, the average number of people infected for every contagious person. The original COVID virus infected two to three people per infectious person, with subsequent variants becoming increasingly transmissible, at a rate of around five to seven new infections per contagious person.

Person-to-person or person-to-animal contact isn’t the only way the virus is transmitted. Contaminated materials like clothes and bedsheets can also be vectors of spread, but frequent and thorough hand-washing is still the most effective mitigation strategy. It’s likely that there is also some limited respiratory spread, though not as significant as with COVID-19, Bogoch told The Dispatch.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a “level two” alert, advising “enhanced precautions” to avoid close contact with infected persons and animals and with materials that may have been in contact with infected individuals. With cases rising in the U.S. and abroad, the CDC activated an emergency operations center to coordinate the response to the virus.

Some communities are particularly vulnerable to contracting monkeypox. Many of the cases discovered so far are in the gay community—what epidemiologists call the community of “men who have sex with men” or MSM. “It’s not clear how the people were exposed to monkeypox,” the CDC website says, “but early data suggest that gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men make up a high number of cases.”

This association prompts a particular set of public health problems. The CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) both make clear that this is a communicable disease like any other, and isn’t specific to a particular demographic or community. Bogoch calls for a combined approach of honesty—about the presence of the disease in this community—and respect to address the specific vulnerability.

“This community has always faced stigma and discrimination,” Bogoch said, so it’s important to “bring the community into the fold” in response to the outbreak, with clear communication and dialogue with public health officials.

Another piece of good news: A vaccine already exists. The monkeypox virus is similar to the virus that causes smallpox, though the diseases themselves are different and monkeypox is significantly less severe than smallpox. The WHO reports that the smallpox vaccine could be as much as 85 percent effective against monkeypox, and an additional vaccine specifically to prevent monkeypox was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2019, though it’s not yet widely available.

It’s still unclear if widespread vaccination will be necessary. Remich, who helped develop both the Ebola and COVID vaccines, says that vaccinating even specific members of the public writ large should wait until we know more about the vaccines and the spread of the virus.

Bogoch, however, suggests targeted vaccination in at-risk populations. That includes making vaccines available in places frequented by the MSM community, in sexual health clinics, to healthcare workers who treat at-risk populations, and in shelter and prison populations. These vaccines could be administered “pre-exposure prophylactically” or “post-exposure prophylactically”— before or after a person has come in contact with the virus to prevent infection.

The United Kingdom, which has recorded almost 800 confirmed cases mostly in the MSM community, has recently adopted this approach to vaccination, offering the smallpox vaccine to some men particularly susceptible to exposure. Similar programs in New York City and Washington, D.C., quickly ran through their supply of the two-dose Jyennos vaccine that they made available to the MSM community, men with multiple sexual partners, others in the LGBTQ community, and other high-risk individuals. The Biden Administration announced Tuesday that it would send increased stocks of the vaccine from the national stockpile to areas, like big cities, that needed it.

The COVID pandemic is a double-edged sword when it comes to fighting this new outbreak. On the one hand, Bogoch said, “This is the most health-literate population in history—everyone has had a crash course on public health, and that can’t hurt.” Plus, the infrastructure for the public health response—from vaccines, to communication, to government agencies primed to deal with diseases—is already in place. On the other hand, pandemic fatigue, vaccine hesitancy, and public distrust of public health officials and institutions could hinder a swift and effective response.

“Anytime a public health intervention becomes politicized,” Remich said, “it’s no longer fit for purpose. They’re designed to keep the public safe and healthy,” not to be used as a political prop.

To Bogoch, containing this virus and eliminating community spread could be an easy win if governments act quickly to stand up a response from the global level down, though some are already arguing that the reaction has been too slow: “It has the potential to begin to build back trust in public health and in government.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.