For decades, American foreign policy in the Middle East was characterized by indifference to human rights and democratic governance. And on the rare occasions that leaders were called upon to justify their propensity for kings, presidents for life, and beribboned “colonels,” they gestured toward the exigencies of the Cold War. But the Cold War is done, 9/11 upended both U.S. policy and attitudes in the Arab world, and the Arab Spring officially inaugurated what looked like a new era. Nonetheless, two decades later, the freedom interregnum in American policy is done, and there is no clearer place the new-old policy is on view than in Syria.

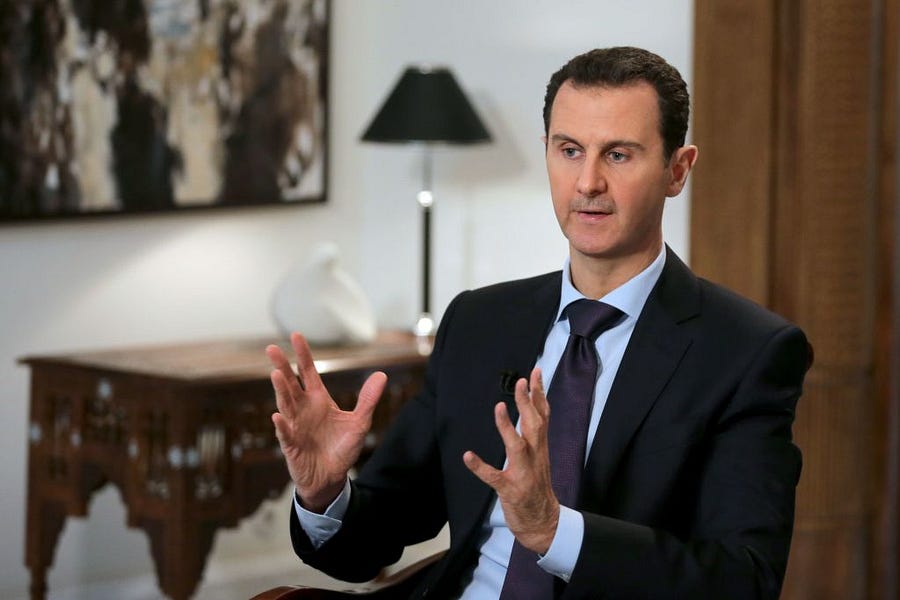

As many have painstakingly detailed (here, here, here, and here), the Biden administration has unofficially reconciled itself to the idea that the best outcome in Syria is a Tehran-backed Bashar al-Assad regime. In addition to the likely withdrawal of U.S. troops in northern Syria, Secretary of State Tony Blinken—his memories of the Holocaust apparently shoved to the side—has signed on to a tacit agreement not to enforce Caesar Act sanctions against Arab leaders looking to normalize and subsidize Assad. The Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 mandates sanctions against Assad supporters, war criminals, and others complicit in Assad’s war on his people, and bars normalization.

As ever, there are some logical reasons to embrace Assad, or barring a full-on love-in, quietly accept the efforts of others to mainstream him. Biden administration officials have made no secret of their desire to turn America’s back to the post-9/11 wars of the Middle East, re-enter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran, and confront growing threats from Communist China. And it’s not like the problems of Syria are on the cusp of resolution, missing only an engaged team in Washington. Indeed, the situation on the ground in Syria has grown only messier in recent years.

Many of the players remain the same—Assad himself, with Russian, Iranian, and Hezbollah backing; Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), backed by a few hundred U.S. and allied troops; Turkey, focused intently on the Kurdish dominated SDF and Turkish-backed forces; ISIS, including about 10,000 detained in various SDF prisons, and tens of thousands—including a large ISIS contingent—at the al Hol displaced persons camp; al-Qaeda and its erstwhile offshoot, Ha’yat Tahrir al Sham. Anti-Assad rebels continue to control parts of Idlib province in Syria’s northwest, with much of the rest of the country under Damascus’ control, although Dara’a in the southwest (where the Syrian uprising began) has once again become restive.

Approximately 600,000 people have died in Syria, more than 100,000 have disappeared, and there are millions of displaced, internally and externally. Russian forces have regularly targeted civilians, the Assad regime has frequently violated the laws of war (with chemical weapons and barrel bombs), and the pandemic has made a bad situation for many even more dire. As if there were not enough players, nor enough manmade and natural disasters, Iran has also continued to use Syria as a waystation to transfer increasingly advanced weaponry to its proxies, which has brought Israel into the mix. The Israeli military targeted Damascus earlier this week, three days after an earlier, similar strike.

Small wonder, in light of this cataclysmic disaster, that successive presidents have adopted Barack Obama’s callous dismissal of Syria: “Unless we were all in and willing to take over Syria, we were going to have problems,” he told a press conference back in 2016. War, he might have said more simply, or capitulation. So capitulation it is. What does that look like?

After the beleaguered king of Jordan met with President Joe Biden in July, he ran full tilt at a reopening to Assad, attempting not simply to warm bilateral ties but to broker readmission to the Arab fold. The implication was clear: The Biden administration had given a green light to a warm-up with Assad. And so the warming began: A gas pipeline from Jordan and Egypt to Lebanon through Syrian territory (with Team Biden reportedly recommending means to evade U.S. sanctions), border opening with Jordan, ministerial visits in Amman, and, per a secret Jordanian plan, the eventual withdrawal of all foreign troops from Syria.

And more: readmission to Interpol; a seat on the World Health Organization’s executive board; a ministerial visit to Beirut. There was a bilateral meeting between Egypt and Syria’s foreign ministers at the United Nations General Assembly; a confab between the United Arab Emirates’ and Syrian economic ministers at the Dubai Expo; and rumors abound of an imminent Syrian-Saudi rapprochement—though to be fair, rumors also abound that the Saudis have decided against cozying up to Assad.

What will it all mean? In the status-quo-ante dreams of D.C. fixers too young to know better (or perhaps too arrogant to care), Assad will reassert control over all of Syria, and then a happy confederation of Israel, the United States, and Russia will give the Syrian dictator the confidence he needs to finally oust Iran and Hezbollah from his lands. Turkey and Russia will make sure there’s no homeland for ISIS or al-Qaeda or other pesky Salafis who threaten our national security. Neat, tidy, and possibly with a cherry on top.

But this is not a realpolitik recipe for success. It is a sloppy, oft-tested, game of risk in which the parties truly engaged in Syria’s future—Tehran, Moscow, and Assad himself—crush the incompetent boobs who thought they were cleverer than their counterparts. Israelis entertain the notion that Russia would like to see Iran out of Syria. Americans have long believed Assad is desperate for Western recognition, and that Iran can be propitiated by renewed friendship with its Damascus proxy. Jordan believes Assad’s normalization will get ISIS/Iran/other troublemakers off their borders and enable economic flourishing.

Here is the reality: Assad will never drop Tehran because he owes his life to Iran. Iran will never drop Assad because the regime has had every possible incentive to do so over the last decade, and has never wavered. Together, Assad, Iran and Russia cannot crush their opponents because … 10 years of fighting has failed to make that happen. So what should the United States do? As always, the best guide is the intersection of morality and strategic interests.

The United States must follow the letter of the law and demand the pipeline through Syria is shut down. Team Biden should recommit U.S. troops to the fight in northern Syria, and reconcile itself to the notion that a) betraying another ally is a bad look; and b) that the battle inside Syria hardly distracts from the larger mission on China. Arab leaders must recognize that Assad will betray them and their interests, much as Iran’s proxies in Lebanon do every single day.

It’s time to get back to the United Nations prescribed negotiations for Syria, plan a successor to Assad and remind him that he can never, ever be readmitted to the civilized world. Will that work? Not without serious commitment, which does not seem forthcoming. But it is one thing to fail with the best of intentions, and another to condone the wanton murder of more than a half a million people without a thought for justice or decency.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.