This piece has been adapted from David French’s French Press latest newsletter, which is available to subscribers only. We’re making this version available to all readers. One note: It was sent early Thursday evening, before Twitter appended a warning to one of Donald Trump’s tweets about the riots in Minneapolis.

“Boy, that escalated quickly.” Those words, from the greatest journalist of all time— San Diego’s own Ron Burgundy—have echoed in my mind ever since word leaked that Donald Trump was responding to Twitter’s decision to fact-check a series of his tweets by issuing an executive order targeting social media. Long-simmering battles about social media censorship and social media bias are coming to a head. The president isn’t just tweeting. He’s taking legal action. This afternoon he signed an executive order that takes aim at the speech policies private online platforms..

What the heck is going on? What should we think about the exchange? Is there a solution to our social media wars?

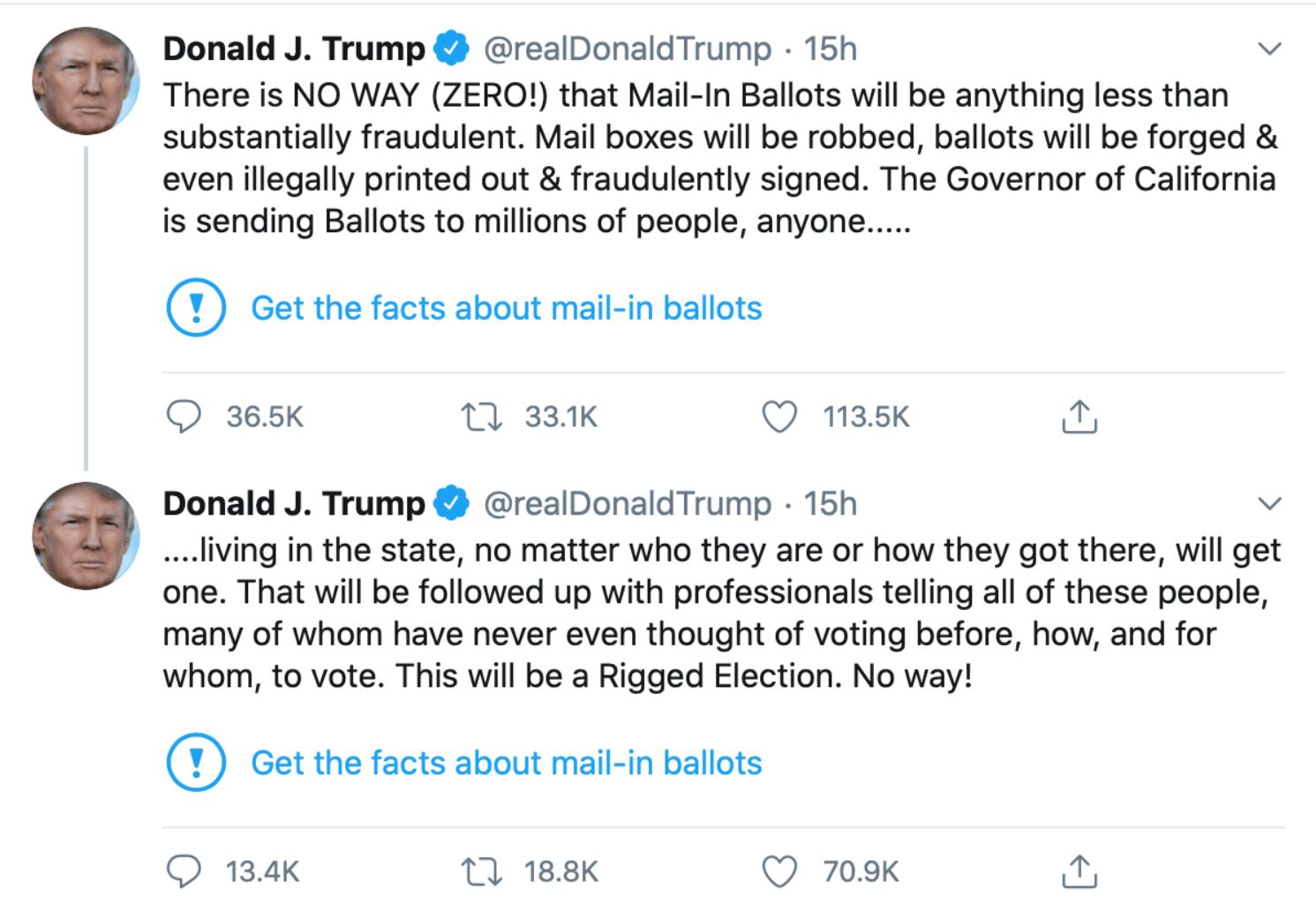

The issues are so complex that I feel a bit like Inigo Montoya in the film Princess Bride. “Let me explain. No, there is too much. Let me sum up.” The online cannon shot that brought long-simmering tensions to a head was a tiny blue exclamation point attached to two Trump tweets. You can see them here:

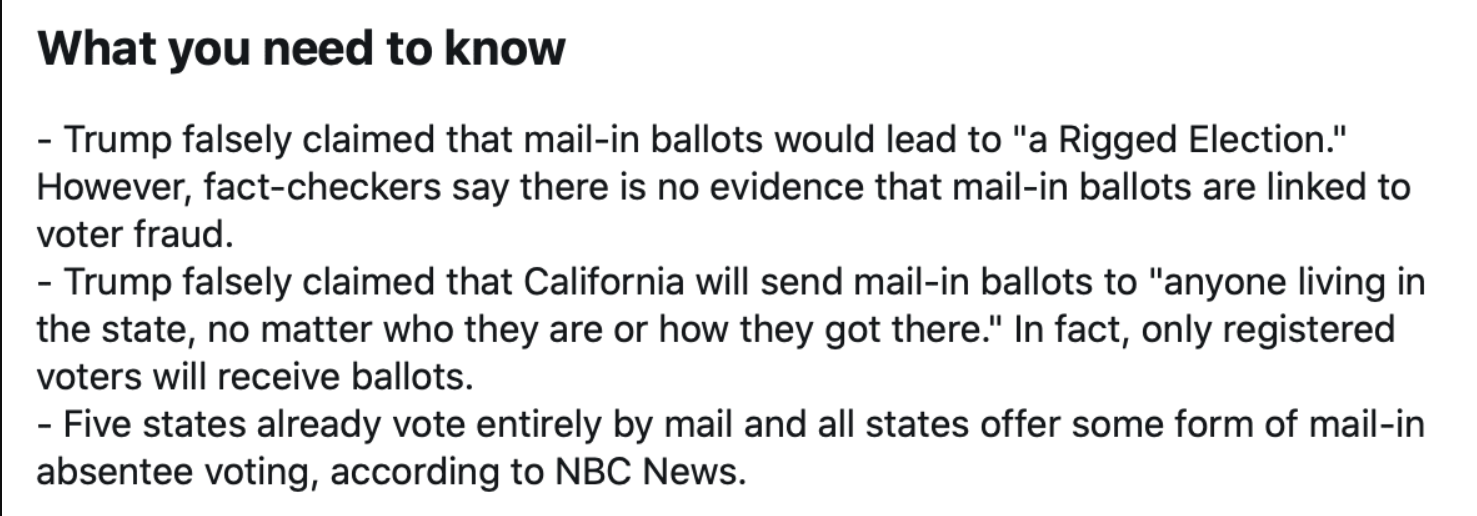

Clicking the exclamation point led you to this statement:

Twitter didn’t censor the president, but it did single out his tweets, exercised editorial discretion to rebut his tweet, and did so in its corporate voice. Twitter’s action thus was almost perfectly constructed to reignite a raging legal argument that centered around two often-misunderstood terms—“publisher” and “platform.”

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has two key provisions. The first simply declares that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” In plain language this means that Facebook can’t be held liable for the content of my posts. Facebook is a platform for my speech, but I’m still the speaker. Facebook is not.

The second provision adds an important twist:

(2)Civil liability No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of—

(A)any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected

This is the provision that explicitly allows Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Yelp, and virtually any other online platform to moderate user content without being held liable for user content.

If you ever hear anyone say that “Section 230 requires tech companies to be unbiased,” that’s the equivalent of a person opening their mouth and saying, “I have no idea what I’m talking about.” Section 230 explicitly permits moderation, and it explicitly permits corporations to make their own judgments about moderation, even if that moderation bans or restricts speech the First Amendment would protect.

And it just so happens that this provision is the great engine of free speech online. It has created the modern internet marketplace of ideas.

How is that possible? How does a statute that permits censorship empower free speech? To answer the question, a brief history lesson is in order. Section 230 is born from two conflicting court cases involving two early internet companies—Compuserve and Prodigy.

In 1991, a federal district court dismissed a defamation lawsuit against Compuserve on the grounds that Compuserve did not exercise any control at all over users’ speech. Four years later, a New York state court judge reached the opposite conclusion, holding that Compuserve’s competitor, Prodigy, could be held liable for user content because it moderated user posts.

Taken together, these cases put internet companies in a difficult position. Let any and all content on your platform, and you’ll quickly be overwhelmed with the raw sewage of human nature, limiting your reach to the wider public. (And if you think “anything goes” platforms have broad appeal, ask yourself the last time you visited Gab.)Yet if you choose to moderate content, then you open yourself up to immense liability for speech that you have no reasonable opportunity to research and fact-check.

Section 230 was the answer, and the modern internet took off. As I wrote earlier this year in Time, for 24 years we’ve taken for granted our ability to post our thoughts and arguments about movies, music, restaurants, religions, and politicians. While different sites have different rules and boundaries, the overall breadth of free speech has been extraordinary.

So, what’s the problem? Well, if I can be so bold as to modify the legendary words of Colonel Jessup, from a Few Good Men, I can explain. Reader, we live in an online world that has walls, and those walls have to be guarded by men and women with laptops. Who’s gonna do it?

The traditional conservative and civil libertarian answer to that question has been simple—the private citizens who built their private companies guard their own virtual walls. We enter and use their products according to the rules they set, and if we don’t like it, we click to the competing company across the virtual street.

That’s the approach that we’ve taken at The Dispatch. We’ve constructed our own walls, and within those walls we monitor the comments section in the effort to make sure that we maintain a unique sense of community and a higher level of dialogue that you can find in virtually any other news site on the web. (Along those lines, some of y’all need to chill out. You know who you are.)

Now, here’s where things get even more complicated. Lots of armchair lawyers with Twitter accounts will shout at the top of their lungs that social media companies have to decide, are they a publisher or a platform? No, they don’t. They can be both. The Dispatch is both. We’re certainly a publisher of our edited content. We’re corporately responsible for the edited pieces we publish. But we’re a platform for our moderated comments.

The distinction is typically rather easy to make. Our columns and newsletters don’t go out unless they’ve passed through our corporate process of drafting, editing, and reviewing. So the product plainly belongs to both the author and the company. The comments, by contrast, pop up instantly on the site as soon as the reader presses “Post.” That speech is yours and yours alone, even if we later delete it because you called another Dispatch member a “lying dog-faced pony soldier.”

My Facebook posts are my speech. They go up publicly, immediately. To the extent that Facebook exercises any control, that control comes after the fact. At the same time, Facebook has its own speech. It’s a publisher of that speech, including its press releases, its corporate statements, and any summaries of news that it prints. The same principle applies to Twitter. Donald Trump’s tweets are Trump’s speech, not Twitter’s. Twitter’s fact check was Twitter’s speech, not Trump’s.

This is common sense. Let’s take this offline to make it even more plain. Imagine a town hall meeting like, say, the town hall meetings in Pawnee:

If an angry citizen takes his turn at the microphone, should the city be liable for what he says—even though the city provided the microphone and the chance to speak to an audience? What if he goes on a tirade and starts insulting a member of the audience, should the city be liable for his speech (and the speech of others) if it shuts off his mic? Does an attempt to impose rules on speakers transform the city into the speaker?

Or take the analogy to the classroom. Is the professor liable if a student slanders another student? If the professor tries to enforce rules of civility, should that render him or her liable for student speech?

So no, Section 230 isn’t a “giveaway” to tech companies. It’s instead accurately defining who is speaking when a consumer posts his or her own content, and it’s protecting the right of providers of interactive computer services to create their own unique products.

Now, here comes the problem—many millions of Americans do not like either the terms of service or the corporate interpretation of the terms of services on some of their favorite platforms. The terms are biased. Their application is inconsistent or unfair. And rather than seeking to persuade the platforms to change their policies or walking away and joining different platforms (the best approach), they instead seek to use the government to force social media companies to change their own rules.

And they have a powerful ally. Today, Trump responded to Twitter’s fact-check by signing an executive order that directs federal agencies to issue rules reinterpreting Section 230. The order directs the secretary of commerce to “file a petition for rulemaking” to “clarify” the “conditions under which actions restricting access to or availability of material is not ‘taken in good faith.’”

It also directed the Federal Trade Commission to take action “to prohibit unfair or deceptive acts or practices,” including “practices by entities regulated by Section 230 that restrict speech in ways that do not align with those entities’ public representations about those practices.” The order also directs the attorney general to create a working group of state attorneys general to determine whether social media companies are in violation of state laws prohibiting unfair or deceptive acts or practices.

And lest you have any confidence that the resulting regulatory action will be lawful, Attorney General Barr made a series of statements at the signing that are at odds with existing law:

Section 230 plainly permits companies to restrict access to content it deems “objectionable” without becoming a publisher. That’s the law. Trump’s executive order can’t override it—nor can his rules drafted by his executive agencies. He can, however, can create a tremendous legal mess and spawn an avalanche of lawsuits.

State interference with the speech policies of private corporations is a direct threat to civil liberties. Americans should be able to construct online communities that reflect the culture and ethos of the company’s founders and leaders. While I may argue for policies that better reflect my own values, ultimately I defer to the individuals who built the platform. Their culture and their rules are their decision.

The contrary view is sometimes rooted in a staggering sense of entitlement—a declaration that I somehow have a right to use a platform I did not create under the terms that I wish. And when it comes to social media companies, I’m asserting that alleged “right” without even paying for the service.

Since the conflict between Trump and “Big Tech” has officially moved beyond bluster and into legal action, let me close with a modest proposal. Social media companies have coddled Trump long enough. Twitter especially has granted him far more leeway than it grants any other user. If Twitter applied the same rules that it applies to other users, he would have been forced to delete multiple tweets or face the suspension of his account.

Faced with Trump’s relentless stream of abuse and misinformation, Twitter chose perhaps the worst possible option—applying unique fact-checks to the president that almost certainly won’t be applied to other leading public figures. In other words, it continued to single him out.

Stop.

Trump is massing the power of the executive branch of government in a direct attack on American liberty. American citizens who build and operate their own companies should draw the line in the sand. Twitter (and every other social media company) should not only challenge unconstitutional regulations, it should tell Trump his special privileges are over.

To them, he shouldn’t be President Trump. Instead, he should be Donald Trump, and Donald Trump has to comply with the terms of service. Dancing around the bully hasn’t placated the bully, and the bully is using a platform that’s not his to harm innocent people—like the family of Joe Scarborough’s former aide, Lori Klausutis. It’s time that the president relearn what it means to be a citizen, and citizens play by the rules.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.