On September 9, 1944, mere days after the liberation of Paris by Allied forces in World War II, one of the most revered English minds of the 20th century penned a warning that looked beyond the immediate conflict toward the unthinkable—a third world war. C.S. Lewis was concerned about a lingering public attitude of apathy that threatened to leave Great Britain ill-prepared for her own defense in the years to come, just as a similar climate had sapped its strength in the age of appeasement in the 1930s.

“We know from the experience of the last twenty years that a terrified and angry pacifism is one of the roads that lead to war. I am pointing out that hatred of those to whom war gives power over us is one of the roads to terrified and angry pacifism. … A nation convulsed with Blimpophobia will refuse to take necessary precautions and will therefore encourage her enemies to attack her.”

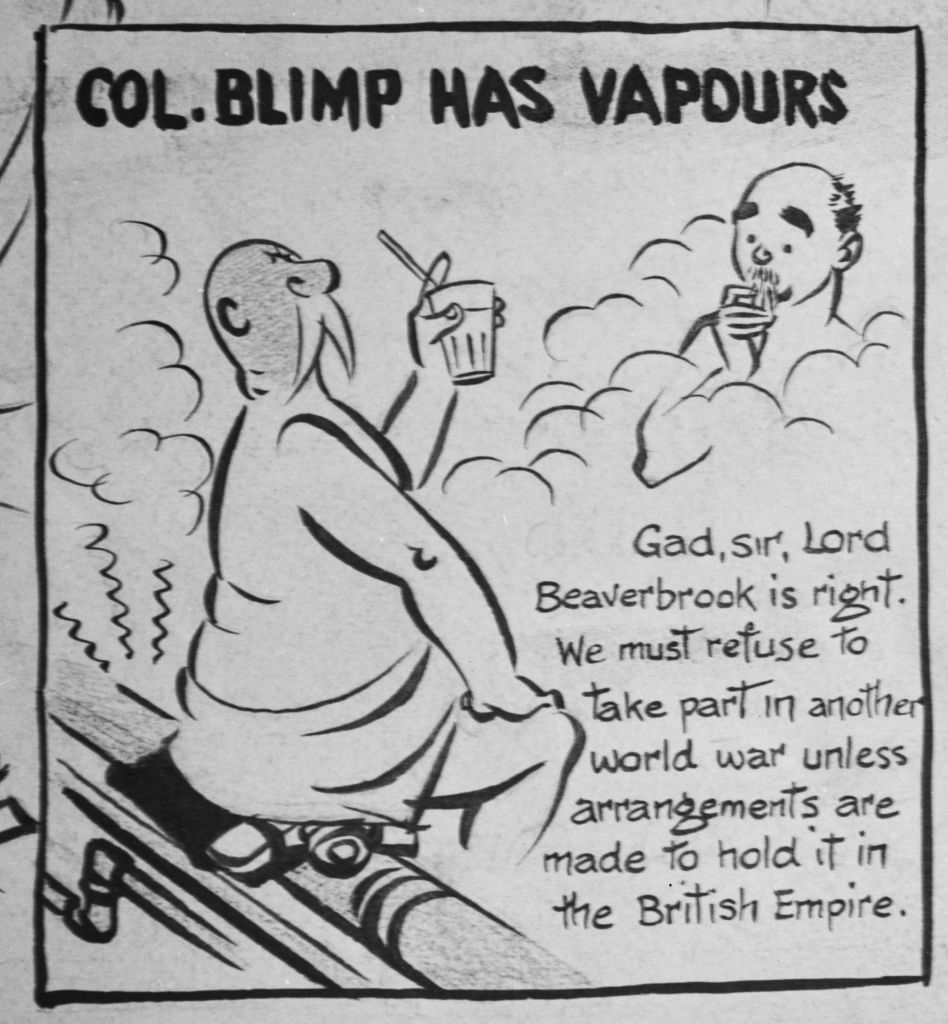

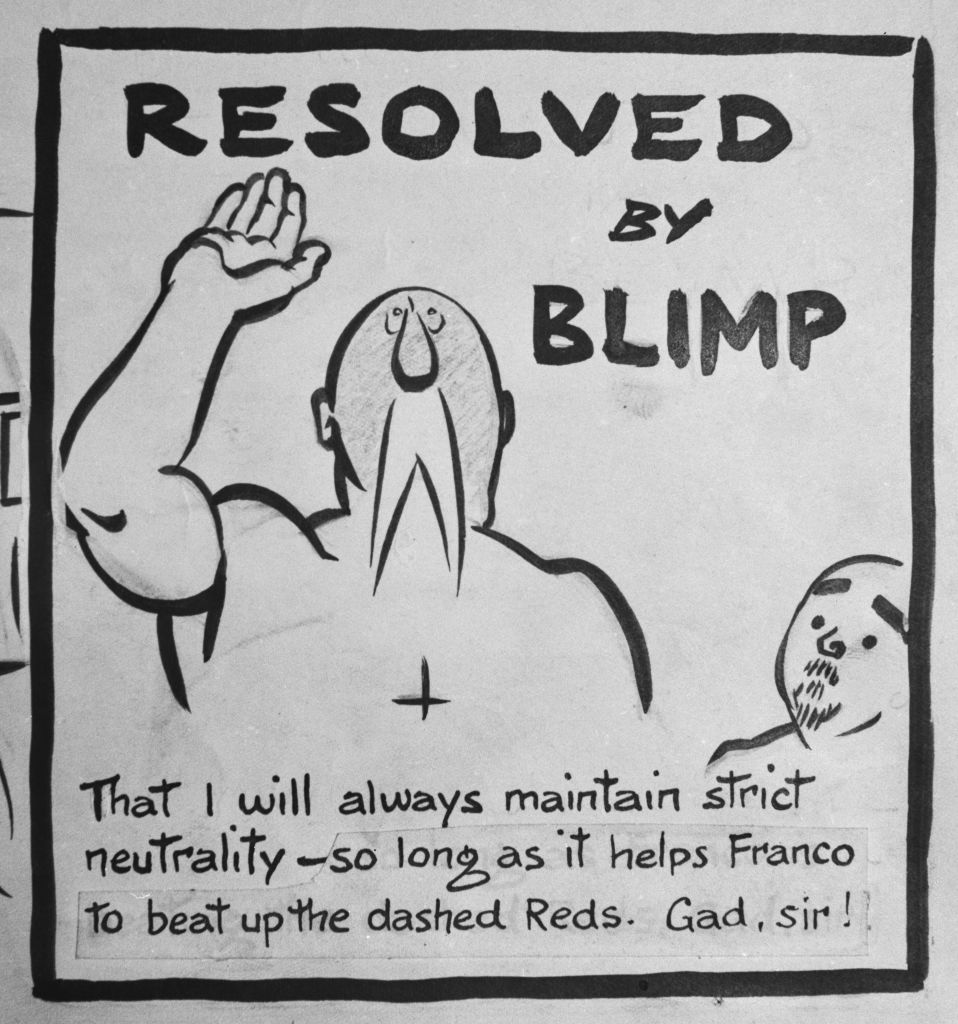

What did Lewis mean by Blimpophobia? It’s an allusion to a popular British political cartoon of that era, centered on the character “Colonel Blimp,” which lampooned the stereotypically out-of-touch ruling class that had fallen out of favor with the British public during the 1920s-1930s.

Colonel Blimp is long gone from the editorial pages, but the kind of dangerous stupidity that he represented is alive and well. It is easy to see similarities between Britain’s Blimpophobia of the 1930s and 1940s, as described by C.S. Lewis, and the rise of America First today. And many modern American Colonel Blimps continue to out themselves in their public statements regarding the war in Ukraine, which is now a year old.

The shadow of Colonel Blimp.

Colonel Blimp was the creation of Sir David Low, considered one of the most influential political cartoonists of the 20th century. The colonel sported a walrus mustache, a stately paunch, and carried an air of the old British aristocracy. Blimp invariably found himself pontificating on world events while wrapped in a towel, red faced, and enjoying a good sauna or Turkish bath. He came to represent the confused, contradictory, but no less confident attitude of British officials in the 1930s: He was befuddled but well-meaning, and he consistently made bold but incoherent statements on domestic and foreign affairs.

Colonel Blimp hit home for many British subjects disillusioned by their nation’s leadership from World War I onward. “It may well be that the future historian, asked to point to the most characteristic expression of the English temper in the period between the two wars, will reply without hesitation, Colonel Blimp,” explained Lewis.

Low habitually used Colonel Blimp to lampoon Britain’s confused, contradictory, and accommodating treatment of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and other rising threats in Europe and Asia:

“If the Abyssinians don’t stop defending themselves, Mussolini will take it as an act of war … ”

“There’s only one way to stop these bullying aggressors—find out what they want us to do and then do it … ”

“Hitler only needs arms so that he can declare peace on the rest of the world.”

Sound familiar? Low consistently maintained that Blimp was not associated with any one political party or ideology. Blimp was representative of what Lowe called, “slapdash stupidity,” which manifested across the political spectrum of the 1930s. Not only was Colonel Blimp not limited to one political party, he was not limited to one nationality. Low’s cartoon featured special appearances by Colonel Blimps from across the globe. After all, stupidity, which was at the heart of Low’s creation, casts its paunchy, whiskered specter over peoples of all colors, creeds, and nationalities. Naturally, America is no exception.

Will the real Colonel Blimps, please stand up?

The American branch of the Blimp dynasty has thrived in the flesh. They may not sport the walrus mustache, the bloated stomach, or the manners of a country squire, but the unyielding self-contradiction and stupidity remains.

Consider Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, who insists we must cease our support of Ukraine, lest we give the Chinese the idea we are not serious about our commitments:

Or the impeccable logic churned out from the Charlie Kirk branch of the House of Blimp:

And then there’s national divorce enthusiast and matriarch of the Georgia Blimps, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene.

Finally, and most distinguished of all, is former President Donald Trump, who recently declared:

I want to make it so that Ukraine and Russia have to fight, and fight for the last time. And we’ve got to make peace. If we don’t, if we don’t make peace, if we just keep sending everything, you know, we’re sending everything over. They’ve got to fight for the last day, for the last two days. This thing has to stop, and it’s got to stop now. And it’s not going to stop if we continue to just load something up. Now I will say this. If Russia was not a willing participant, I would have a different mindset. But right now, there’s no reason for them or anybody else to sit down.

Some of these Colonel Blimps, unaware of their own Blimpishness, lash out against those they perceive as the true Blimps. They call out “RINOs,” the “woke,” and the “establishment” with regularity, having exchanged their bathrobe and Turkish bath for the podcast headphones, the congressional floor speech, and the Truth Social account.

In terms of American foreign policy, they bristle at America’s involvement in world affairs, purportedly as a rejection of the Bush-era foreign policy, particularly the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. To them, the “neocons” (an increasingly expansive term for anything they do not like), are the real Colonel Blimps. To keep these neocons out of power they will do anything, even damage their own party’s electoral chances. They will even let Ukraine fall, while insisting they are doing so for the sake of Taiwan.

Lewis recognized that a reflexive opposition to an engaged foreign policy, rising out of a distaste for those in charge, was setting the stage for disaster. Prior to his fame as an author, theologian, and thinker, Lewis was a distinguished veteran of World War I and a keen observer of his country’s mood during the interwar period. He had seen the results of the “angry pacifism”—it had “led to Munich, and via Munich to Dunkirk.” In other words, frustrations aimed at the past had caused Britain to suffer near destruction in the present.As the war in Ukraine hits the one year mark, our nation must ask itself whether it will be led in the 21st century by a terrified and angry pacifism, buttressed by a confused and contradictory foreign policy, or whether it will stand up against stupidity in its many iterations and manifestations. People are dying. It is not the time to listen to our home-grown Colonel Blimps when they stand in solidarity with dictators who demand capitulation and call it peace.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.