HEBRON, West Bank—In the city of Hebron sits a 2,000 year-old building, built by King Herod the Great. Jews know it as the Tomb of the Patriarchs.

For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the building is why the city holds immense religious significance: It is the burial site of biblical patriarchs and matriarchs shared by the Abrahamic religions.*

One the Jewish side of the building, the walls are lined with religious texts and areas where residents gather to pray and reflect. Visitors shuffle by quietly to visit the tombs of Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah.

To Muslims, the building is known as the Ibrahimi Mosque. Islamic tradition holds that the prophet Mohammad stopped by the tomb on his journey from Mecca to Jerusalem. The site makes Hebron one of Islam’s four holiest cities, following Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem.

The building, like the city, has been the site of both prayer and worship—and also of bloodshed, violence, and division. Many attacks and beatings there have targeted Jewish settlers. And in 1994, an Israeli-American shooter entered the mosque and killed 29 Palestinians. The aftermath of the attack would widen the split between the two groups: The Israeli Defense Force (IDF) closed the mosque for months and established military checkpoints. The building itself was divided into a Muslim and a Jewish side, partitioned by bulletproof glass.

Currently, Jews can enter only by the southwestern side, while Muslims can enter only by the northeastern side of the building.

The building and the city—20 miles south of Jerusalem—are emblematic of the Israel-Palestine conflict that has bedeviled the region for years.

But Middle East watchers say a wind of change is blowing in the region that, seemingly overnight, upset long-nursed adages about the intractability of tensions in the region. The Abraham Accords, a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and neighboring Gulf Arab countries negotiated during the Trump administration, powerfully illustrate these shifts.

With the U.S.-brokered accords, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel announced a public normalization of relations. Subsequently, Bahrain in September 2020, Sudan in October, and Morocco in December, also announced plans to normalize relations with Israel. (Though instability within the Sudanese government has since paused efforts there.)

The United States’ perceived withdrawal from Middle Eastern affairs has much to do with these pragmatic olive branches, experts told The Dispatch. In the wake of a waning U.S. presence, Israel is increasingly seen as a counterweight to the threat proffered by Iran and its allies in the region.

The Obama and Trump years showed that both Democratic and Republican administrations are eager to withdraw from the Middle East. President Joe Biden accelerated the trend, with the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan serving as the ultimate case in point.

It’s unclear whether, given the current American malaise toward taking a proactive role in the Middle East, the U.S. will successfully capitalize on the warmer relations between Israel and its neighbors. Biden was somewhat slow to embrace the Abraham Accords, and has yet to expend much political capital on the Israel-Palestine conflict. He’s making his first trip as president to Israel, Palestine, and Saudi Arabia this week. He will also meet with other Gulf States and hold a virtual summit with Israeli, Indian, and UAE leaders.

In a statement in June, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Biden’s upcoming meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid will focus on discussing the country’s “security, prosperity, and its increasing integration into the greater region.”** His meeting with Palestinian Authority leader Mahmoud Abbas will focus on reiterating the president’s “strong support for a two-state solution, with equal measures of security, freedom, and opportunity for the Palestinian people.”

“The changes that we’re seeing take place across the Near East are, in a word, unprecedented,” Robert Nicholson, president of the Philos Project, told The Dispatch. “The reasons for the change are complex, they are multilayered, much of it has to do with a shared threat perception on the part of Arabs and Israelis—especially as the threat resides in Iran, but there are other factors in play as well.”

Philos is a U.S.-based Christian advocacy organization that promotes positive engagement with the Middle East and pluralism in the region. It focuses on the Israel-Palestine conflict as well as the plight of indigenous Christian communities, which face persecution and resulting dwindling numbers.

Nicholson said the Abraham Accords, signed in August 2020, felt like a “ray of light breaking through the clouds” amid the COVID-19 pandemic: “It was well known to not just me but almost everyone that Israel had all kinds of subterranean dealings with Arabic states in the region, especially vis-à-vis Iran. But to think that an Arab state, and then another one, and then a third one, and then a fourth one—in the space of just a couple of months—would do this publicly was shocking.”

Those at Philos underscore that while the security and economic aspects of the Abraham Accords remain paramount, the agreement’s religious element should not be overlooked.

“There is a long history between Jews and Muslims and Christians—some of what we’re seeing in this Abrahamic shift is a rediscovery of previous relationships and the previous coexistence between those communities,” Nicholson said.

“The greatest mistakes of American engagement with the Near East until now have been almost always rooted in some misunderstanding of religion and culture. Americans like to think of the world as if it is like America—where liberal democracy prevails, one person equals one vote and where the best idea wins regardless of the people voting,” Nicholson added. “The Near East doesn’t work that way. [It’s] a very old part of the world in which layer and layer of religion and culture have been piled on top of each other and in which social decisions and political decisions are made with reference to … transcendent ideas.”

Most helpful for charting the region’s future will be people with “street smarts about what the region is, what it’s all about … It’s really about creating the next generation of leaders but doing so not in a classroom but through immersion.”

One of Philos’ key programs, the Philos Leadership Institute (PLI), seeks to do that by connecting young professionals interested in the region in a hands-on way. The three- to six-month fellowship includes online classes giving overviews of the religious and political history of the region, weekly Zoom calls, and culminates an intensive, fortnight-long trip to Israel, the West Bank, and Palestine. Last month, the cohort added a stop in the UAE.

“It’s not about coming up with bumper sticker solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” Nicholson added. “I think what PLI does is give people a much grittier understanding of what the region is really like, as opposed to what they’ve read about.”

One PLI participant, Sherly Trujillo, said after returning from the trip she’s found herself bringing up the Philos Project and its work in the Middle East during conversations with friends and classmates. Trujillo, from Colombia, is an undergraduate student studying biblical languages at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago.

“I think it’s important because many Christians don’t have any idea about the situation in the Middle East,” she said.

One of the more impactful activities for her was a visit to Israel’s northern border with Lebanon and a war game simulation. Fellows had to consider how to deal with a host of security and political questions. “It made me realize how complicated life is in Israel,” she said.

The trip includes touring holy sites such as the Western Wall, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and this year, the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi. It also includes a crash course on the mix of cultures and influence of religion in the region. The trip also does not shy away from exposing fellows to complicated realities. They meet with political moderates and extremists on both the Israeli and Palestinian side.

Max Prowant, a 20-something working in Washington, D.C., in the process of getting a doctorate focused on the Middle East, went on the trip in June. He currently works for the nonprofit human rights organization In Defense of Christians. The visit to Hebron stood out most vividly to him.

On a stiflingly hot June afternoon, he and around 25 mostly American young professionals squeezed into the a small, upper-story stone house belonging to a Palestinian man named Abed as part of a day trip to Hebron.

For 400 years, the house has belonged to Abed’s family. He traces his family lineage back to Saladin, the legendary Sunni Muslim Kurd who became Sultan of both Egypt and Syria, founded the Ayyubid dynasty, and pushed back the Third Crusade, capturing Jerusalem in the process.

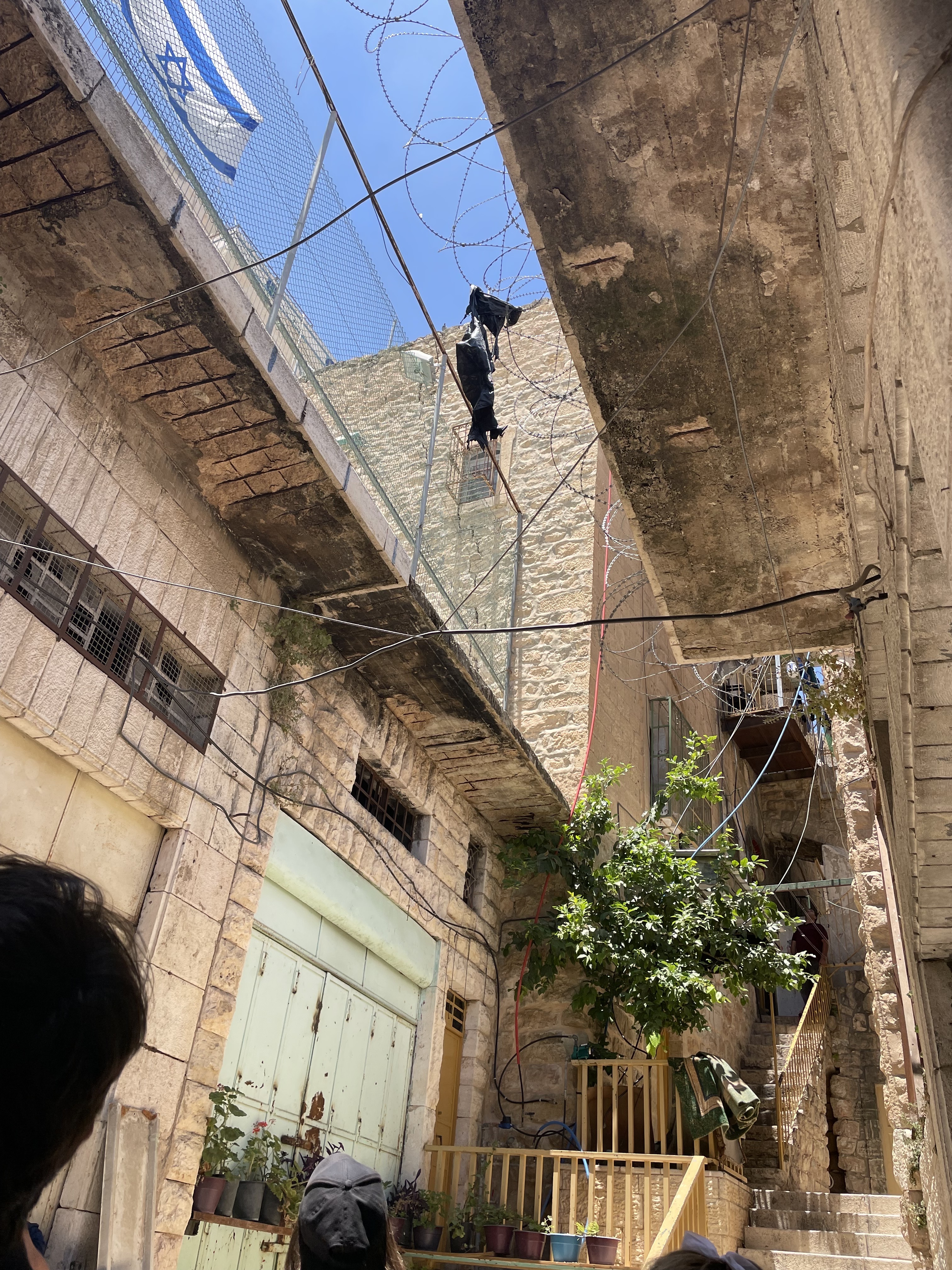

The house now sits against the dividing wall in the Old City of Hebron separating the Jewish quarter from the rest of the city.

The modest dwelling, with its thick walls, offered a respite from the heat that drew not only the Philos cohort inside, but also the neighborhood teenager or two who drifted in with easy familiarity. Outside, the sounds of the streets mingled with the whoosh of hastily-plugged in oscillating fans (the house has no air conditioning). In the living room, fellows sat elbow to elbow on a couch, chairs, a bed, and the floor. In one corner, a small sewing machine sat on a table. In hollowed out shelves in the walls sat stacks of embroidered throws and pillow cases handcrafted by Abed’s wife.

Abed and his family had prepared a late lunch, doling out soda and heaps of steaming Maqluba, a traditional regional dish that features rice, meat, and fried veggies. Maqluba means “upside down,” and Abed flipped the pot onto a serving dish himself, careful not to spill a single grain of rice.

During lunch, Abed talked about what it is like to live in Hebron.

Hebron briefly came under Israeli control after the Six Day War in 1967. During the negotiation process in the 1990s that ultimately produced the Oslo Accords—considered a stepping stone on the path toward a formal peace treaty wherein both sides recognized the legitimacy of each other as a negotiating partner and divided up governing responsibilities—control of Hebron was so disputed that negotiators opened a separate negotiation process to find a compromise. The result halved the city: the Palestinian Authority has both military and civil jurisdiction of the H1 sector, where the vast majority of Palestinians live. In the H2 sector, Israel has military jurisdiction. The latter is where Jewish settlers live alongside around 30,000 Palestinians.

But the dividing line between the two sectors is sometimes as thin as the wall of a house, or fragile as a single pane of glass—such as the round window in Abed’s living room.

Today, that window is sealed off. Because before, Abed said, Jewish settlers on the other side used to drop garbage, stones, and sometimes snakes into the house.

The family has been asked to sell the house to Israeli and Jewish-American organizations several times, with offers they said have reached to the millions. But so far, despite the harsh conditions that chased many of his neighbors elsewhere, the family has refused to leave.

“You can’t really describe how you feel. The only people that feel this type of depression and emotion are those who are living through this on a day to day basis,” Abed said, through a translator.

After lunch, the group went to the Jewish quarter to spend over an hour touring that side and hearing from a Jewish tour guide.

On the other side of the now-walled off window, the Jewish quarter has been built up to sit a little higher. Metal fencing, barbed wire, surveillance towers, and Jewish flags here and there make up a partition. In the shadow of the fence, Jewish children ride their bikes, play ball on a basketball court, and climb on monkey bars in a playground in a somewhat fragile security.

Today, around 1,000 Jewish residents live in their own quarter of the city.

To get to the Jewish quarter from H1, the Philos crew walked through a bustling market, where Palestinian merchants hawk traditional wares like rugs and pottery, chicken and other livestock, dry goods, and shoes and clothing sporting Western brand names. Closer to the checkpoint, the bustle of the market faded, and visitors passed through a turnstile, metal detectors, and passport inspections to clear security.

There, the cohort met with Rabbi Yishai Fleisher, the international spokesman for the Jewish community in Hebron and an outspoken activist for a rightwing coalition of settlers who oppose a two-state solution.

Fleisher sported a beard and a booming voice, and, despite the heat, unflagging energy. For the next couple of hours, he would regale the crew with stories, arguments, and his own take on the region’s politics.

Fleisher started by noting that the Tomb of the Patriarchs is evidence of a historical Jewish presence in the area, documented in the first book in the Torah, Genesis, which details Abraham buying a cave to bury his wife Sarah in what is now Hebron.

Since the Middle Ages, a small Jewish community has lived in the city, but in 1929, Arab assailants killed 67 Jews and attacked others in what is known as the Hebron massacre. In the pogrom’s wake, Hebron’s remaining Jewish residents fled.

Because of the Jewish community’s historical ties to the city, Fleisher pushes back against the projection of its Jewish population as occupiers: “To us it’s absurd because we are the most indigenous,” he said. “The only reason we survive here is because of the tenacity and connection we have to this place.”

The deep commitment to their homes, to the holy sites, and to the land that Abed and Fleisher expressed—despite their competing points of view—is characteristic for people in the region.

Prowant, one of the Philos fellows, said the trip did not result in any “massive shifts of opinion,” for him, but he walked away “feeling firsthand the intensity that everyone speaks of—in particular in Hebron—where you have Israeli settlers, and then the Palestinians literally separated by a single wall of a house …it gave a lot of poignancy to these debates that up until the fellowship I’d seen as kind of academic, about land rights or, you know, who was in the land first. Now you can see the real life human consequences.”

Over the course of the trip, the cohort crisscrossed Jerusalem, Galilee, Bethlehem, Hebron, Tiberius, and elsewhere. Meetings included an Israeli military intelligence veteran to learn about the security concerns over Hezbollah on Israel’s northern border, an Israeli businessman who lives in the Jewish settlement of Ariel, a director and pollster at the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, and others.

Prowant said one of the more valuable aspects of the trip was the chance to talk with speakers after the formal sessions and at times exchange contact information. “When those sorts of channels remain open—I think the prospect for change becomes even greater.”

Since the agreements between the Gulf-Arab states and Israel, development—both economic and relational—has taken off at a rapid clip: through Arab-Israeli summits, the opening of embassies, over hundreds of direct flights between Israel and the UAE, and the flow of billions of dollars in trade and planned investment.

“We are talking about immediate and full normalization across every aspect: tourism, visa-free travel. That’s something unheard of in the Middle East,” Dan Feferman, communications director for Sharaka, told the cohort at one meeting. Sharaka is a non-profit organization founded by young professionals from Gulf states and Israel to promote positive relations between Israel and its neighbors.

Palestinian leaders boycotted negotiations during the normalization process and have portrayed the agreements as a betrayal of the Palestinian people on the part of other Arab nations.

“If you were in my place you would feel that they are backstabbing you,” one member of the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), who espoused views consistent with Hamas, said when asked about his reaction to the Abraham Accords.

“If you talk to any of these countries, and you talk to the people who are supportive of the Abrahamic Accords … they’ll say that’s absolutely not the case,” Feferman said in response to a question about whether the accords have weakened Arab Gulf nations’ support for Palestine. “These are not Zionists … Where they are is a very pragmatic space in the conversation.”

UAE officials have said joining the agreements has not changed their support for Palestinians, and pointed out that the agreements deterred former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from moving forward with a plan in 2020 to annex more territory in the West Bank. As part of the deal, Netanyahu agreed to suspend those plans, at least temporarily.

“We’ve been part of this conflict and we are still part of it,” Ali Rashid Al Nuaimi, chairman of the Defense, Interior, and Foreign Relations Committee in the UAE Federal National Council, told the Philos cohort. Describing the decision to normalize relations with Israel, Nuaimi added: “We found out that we need a breakthrough and doing business as usual won’t solve the issue.”

Feferman said he “wasn’t expecting this kind of a lifting of floodgates of all sorts of regional development that have taken place as a result,” of the Abraham Accords agreements. “My contention is that these are fundamentally changing the Middle East. This is a watershed moment in the history of the modern Middle East.”

Feferman believes that increased engagement may do more to eventually bring positive change to the region, including through more economic opportunity for Palestine, than the last decades of gridlock: “If I had one sentence to say about it, I’d say I think it’s the end of the Arab-Israeli conflict,” Feferman said. “If I had two sentences to say about it, I’d say it’s the beginning of the end of the Arab-Israeli conflict.”

Not all Middle East watchers are as optimistic as Feferman, but many hope the momentum created by the Abraham Accords will continue.

“One of the big themes of this trip for me was seeing people who are willing to explore outside the box of what’s conventional wisdom in Washington,” Another PLI participant, Max Bodach, told The Dispatch. “We saw this on both the Palestinian side and on the Jewish side.”

Bodach is a senior associate at Keybridge Communications, a D.C.-based public relations firm. He described his overall outlook on the region as initially pessimistic. But over the course of the trip, those views began to change. “I walked into this trip a pessimist and I walked out cautiously optimistic … it gave me a renewed sense of passion for this region and a renewed interest to bring my skills and my talents to bear in this region.”

When Nicholson began to pitch the concept of The Philos Project prior to its founding in 2014, he faced accusations of naïveté, often from other Christians. Philos means “friend” in Greek. The name raised eyebrows. Over and over, Nicholson heard the feedback: “What friends? We have no friends. We have Israel and that’s it.”

He believes the development of the Abraham Accords has borne out the optimistic vision Philos articulated and hopes to see grow. “We believe there are enemies and threats that need to be met accordingly. But we also have friends. We think so much about enemies that we forget our friends.”

*July 12, 2022: This story was corrected to read “For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the building is why the city holds immense religious significance.”

**The article formerly said Biden would meet with former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett. We regret the error.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.