Travel back to the last Republican presidential nominating contest eight years ago, and you’d find former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush leading the pack of candidates. Pundits pegged him as the clear favorite, with political strategist Greg Valliere giving him a 50 percent chance to secure the nomination, followed by a 25 percent chance for Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, a 20 percent chance for Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, and a 5 percent chance for “someone else.” Turns out “someone else” was Donald Trump, who dominated the first primary debate a few weeks later.

Now Trump is the clear frontrunner. Could the upcoming primary debates change the outcome of this contest too?

Do primary debates matter?

Presidential debates between the nominees of the country’s respective parties are perhaps the most hyped events of each campaign, but experts generally believe that primary debates—which come first but draw fewer viewers—actually do more to move the electoral needle.

“Scholars who have looked most carefully at the data have found that, when it comes to shifting enough votes to decide the outcome of the election, presidential debates have rarely, if ever, mattered,” political scientist John Sides has written.

By the time general election debates roll around, the two major party candidates tend to be well-known to voters, most of whom have already made up their minds on who to vote for. They watch less to be persuaded and more to “see how their candidate is going to dominate, smear or embarrass the other candidate,” said psychologist Jay Van Bavel.

But nearly 60 percent of primary debate watchers in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012 changed their pre-debate candidate preference, according to one study. The primary debates are “the most important thing prior to any contest actually happening,” adds political strategist David Kochel.

The first primary debate is particularly important. Crowded primary fields like this year’s Republican slate makes it difficult “for some of the more serious contenders to get the airtime they need,” says Kochel. “The debate has the most eyeballs of really any event that takes place in the presidential campaign, and it’s really a contest for airtime.”

Who benefits most?

“Frontrunners very rarely benefit,” says political strategist Dave Carney.

But that doesn’t mean debates can’t change the status quo. A gaffe like then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s in 2011 can sink a campaign, while a viral moment like former House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s 2012 rebuke of CNN’s opening question can catapult polling numbers skyward.

Some say it’s shrewd for Trump, who leads by more than 30 percentage points in national polls, to skip the debates. “It would be stupid for him to debate,” says Carney. “There’s nothing to gain.”

But skipping has its own hazards. Trump’s absence would cede airtime to his opponents. “They’ll get to attack him and say things, and he won’t be able to respond,” said David Urban, an adviser to the former president’s 2016 and 2020 campaigns. “People on that stage will do nothing but whack on the person that’s not there.”

Longshot candidates have little to lose and much to gain from a polling shakeup, which means they benefit most from debates. Even those who fail to win the nomination can still use the debates to bring specific issues into the mainstream the way businessman Andrew Yang did in 2020. They also can audition for a role in the nominee’s administration.

The spin factor.

After the debates, candidates spend a good deal of time in the spin room selling journalists on their performance—and for good reason. “More people hear about the debate from the media’s interpretation of the debate than actually watch the debate. That’s really important,” says Carney.

Media coverage lasts for several days. Hours-long debates are chopped up into dozens of clips, often focusing more on candidates’ personal attacks than their policy differences. Rubio’s campaign faltered after New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie effectively attacked him during a 2016 debate. But that “didn’t happen just because it happened in the debate,” says Kochel. “It became an obsession for the next two or three nights in the national cable coverage but also in New Hampshire coverage.” Rubio finished fifth in the Granite State.

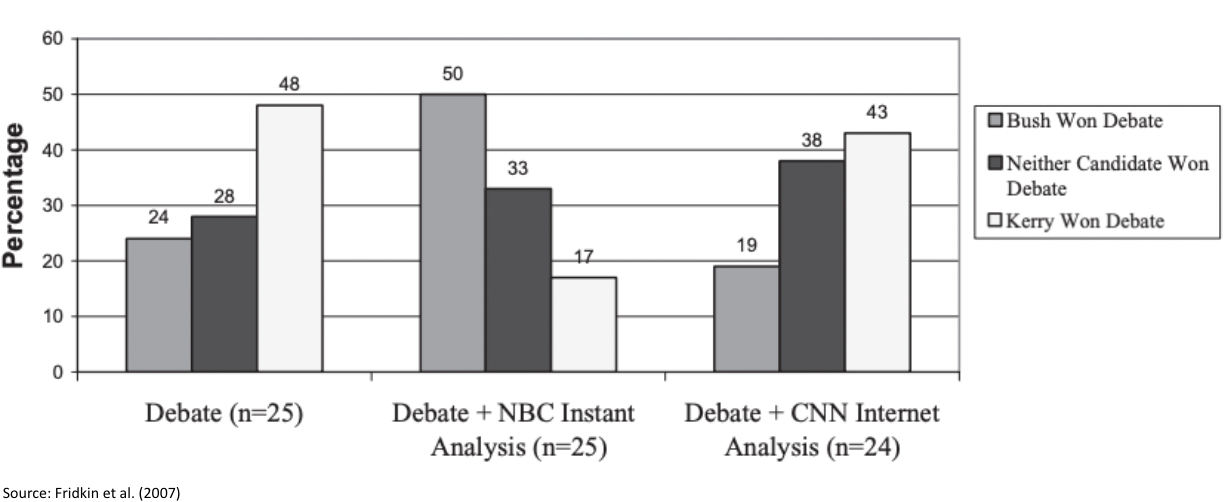

The tone of the coverage matters too, as studies of the 2004 general election contest between George W. Bush and John Kerry have shown. One study randomly assigned prospective voters into three groups before the final 2004 presidential debate: the first group just watched the debate, the second watched the debate then viewed NBC’s analysis, and the third watched the debate then viewed CNN’s analysis. The results were striking, with perceptions of the debate depending greatly on the outlet.

Still, the media can’t manufacture strong performances. That responsibility rests squarely on the candidate’s shoulders, and the upcoming debate is a prime opportunity for each of them to improve their electoral fortunes. Will Trump dominate again, or will “someone else” grab the spotlight?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.