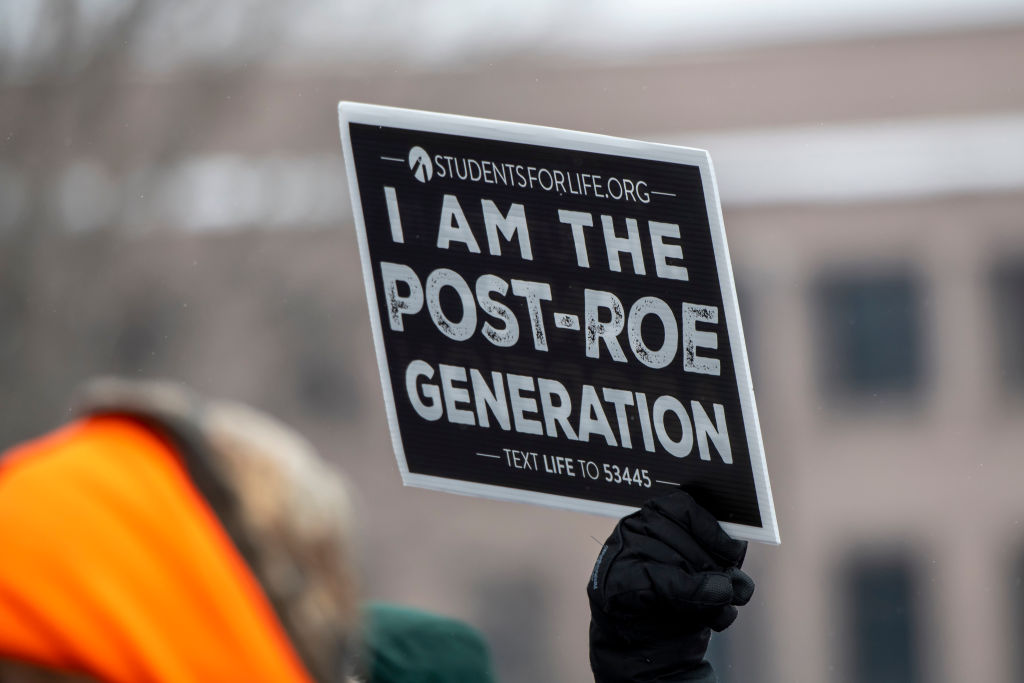

Organizers of last week’s 50th March for Life wanted to send a signal to federal lawmakers this year, so they routed marchers around the U.S. Capitol building before they headed to the Supreme Court.

“One, two, three, four, Roe v. Wade is out the door,” some marchers chanted. “Five, six, seven, eight, now it’s time to legislate!”

Coming up with new chants following last year’s Dobbs Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade may have been the easy part. Now the pro-life movement is wrestling with new strategies and more diffuse goals both at the federal and state levels.

A federal role.

Most Republican lawmakers framed abortion as a state issue ahead of November’s midterm elections, but there’s a growing push for more federal legislation.

“The vast majority of the conversation about life will be in the states and local areas,” Oklahoma Sen. James Lankford told The Dispatch Wednesday. “But the Supreme Court didn’t turn it back to the states. They turned it back to the people and said the people have got to be able to make this decision … so there will be a federal role as well.”

What exactly that federal role will be is up for debate, but it’ll at least include messaging bills. At a rally that was part of last week’s March for Life, Rep. Chris Smith and House Majority Leader Rep. Steve Scalise touted the No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion Act and the Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act. Despite Scalise’s pleading for rally-goers to call their senators, both bills would be dead on arrival in the Democratic-controlled Senate even if they pass the GOP-controlled House.

The same is true for South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham’s 15-week ban with exceptions for rape, incest, and to save the life of the mother. But he said Wednesday that he plans on reintroducing the bill anyway.

For pro-life advocates, who believe human personhood begins at conception and that certain exceptions are inconsistent with that understanding, Graham’s proposal doesn’t go far enough. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth pursuing.

“It is important to be focused on trying to pass what is possible rather than just making a statement,” former Democratic Rep. Dan Lipinski wrote in America magazine in December, concerned about a lack of consensus within the movement around practical next steps. Lipinski was one of the few pro-life members of his party when he left Congress in 2021.

“We can draw on the history of the pro-life movement and some of the cultural and legal successes of incrementalism and realize that, you know, we want to save as many babies as we can right now, and use that as a way to save more tomorrow,” said Katie Glenn, the state policy director for Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America.

Lankford echoed those sentiments. “I’m gonna vote for whatever I can to be able to protect as many children as I can,” he said.

But other pro-life groups, while not actively opposed to Graham’s 15-week bill, say strategies should change in a post-Roe world.

“Fifteen weeks was a great tactic pre-fall of Roe, and it was the right thing to do at that time,” said Kristi Hamrick, chief media and policy strategist at Students for Life of America. “But this is a new day. Incrementalism was a great strategy at one point, and that’s not the point that we’re at.”

“The better priority is for us to address what is now the on-the-ground reality of abortion in America, which is online, no-test distribution of chemical abortion pills,” Hamrick continued. “We’re going to be focusing our efforts there rather than on a 15-week limit.”

Another emerging strategy: developing more economic support for women and their children. Dozens of pro-life leaders released a joint statement last week encouraging “bold” action, stressing affordable health care and childcare, expanded child tax credits, and paid parental leave.

“State and federal governments must take action to eliminate or reduce the significant economic and social pressures that we know drive women to seek abortion in the first place,” they wrote.

Talk of such action on Capitol Hill has already begun. Lankford pointed to Montana Sen. Steve Daines’ bill extending the Child Tax Credit to cover unborn children. Daines is also a co-sponsor of Utah Sen. Mitt Romney’s Family Security Act, which would consolidate existing federal programs into a monthly cash benefit for working families with kids. But while the latter has garnered some tentative bipartisan interest—Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet, known for his work on child poverty, has spoken highly of Romney’s efforts—both bills have a long way to go before becoming law.

State-level action.

In the states, progress on “pro-life safety net issues” is characterized by creativity and often by bipartisanship, according to Glenn. States across the ideological spectrum have opted to expand Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women and extended postpartum Medicaid coverage from 60 days to 12 months—the latter as part of the American Rescue Plan Act. Even liberal California leads the nation in the scope of its funding for the “unborn child option” as part of the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

In Georgia, Gov. Brian Kemp signed a law last year making it easier for nonprofits to operate free maternity supportive housing, and he now wants to expand the benefits of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF) to pregnant mothers before their children are born.

Texas, like Georgia, has declined to opt into full Medicaid expansion under the ACA—which could open billions in federal funds annually—but Glenn touted the state’s million Alternatives to Abortion program, which was allocated $100 million over two years in 2021 to provide support services for pregnant women and their families.

Beyond the pro-life safety net, Glenn said she categorizes current state-level fights over abortion into two other buckets: protections and pills.

The protections—laws prohibiting abortion earlier in pregnancy, which pro-choice advocates view as restrictive—have been enacted in Republican-leaning states, and in some cases those laws are working their way through the courts.

But the state-level pro-life movement also faces new challenges. The FDA’s recent loosening of its Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) protections around the abortifacient drug mifepristone has been a blow, pitting states against the FDA in federal court.

The fact that the two drugs used to induce medical abortion have non-abortifacient uses—mifepristone can be used to treat Cushing’s syndrome and misoprostol to treat stomach ulcers or miscarriage—doesn’t mean states cannot or should not regulate them, pro-life groups argue. A pregnant woman “taking pills at home alone, with nobody to call, and she’s on her own to decide how much blood is too much blood before she goes to the ER—that is the situation that the FDA has endorsed, and it’s incumbent upon states to not rubber stamp them and to do something about it,” Glenn said.

(Lankford and other congressional Republicans sent a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland on Wednesday arguing that a Department of Justice memo allowing for the distribution of these drugs through the mail is legally unsound and should be rescinded or redrafted.)

The pro-life movement faces political challenges at the state level too: Even as pro-life gubernatorial and attorney general candidates performed well in last year’s midterms, state ballot initiative results fell uniformly in the pro-choice column. In September, Kansas voters opted to keep abortion rights in their state constitution. In November, voters in California, Michigan, and Vermont established rights to abortion in their state constitutions, while voters in Kentucky rejected an amendment that would have said there is no right to abortion in its state constitution. In Montana, voters turned down a law meant to protect infants born alive after attempted abortions (such infants are already protected in federal law under the Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002).

“We as the pro-life movement really need to think through how to approach those more successfully,” Glenn said.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.