Fewer issues in America impartially affect all its citizens than gas prices.

With the national average price per gallon of gas at $4.16 (last year at this time it was $2.87), rising inflation, sanctions on Russia, and questions about energy supply, last week President Joe Biden authorized releasing 1 million barrels a day for the next six months from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR).

“This is a wartime bridge to increase oil supply until production ramps up later this year. And it is by far the largest release from our national reserve in our history,” Biden said. “It will provide a historic amount of supply for a historic amount of time—a six-month bridge to the fall.”

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve is what its name sounds like—a massive emergency stockpile of crude oil. Its purpose, the Department of Energy says, is to “alleviate the market impacts of both domestic and international disruptions, caused by weather, natural disasters, labor strikes, technical failures/accidents, political disputes or conflicts.”

In 1975, Congress passed and President Gerald Ford signed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act in response to the 1973 oil embargo against the U.S. During the Arab-Israeli War (also known as the Yom Kippur War), Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries imposed an oil embargo against the U.S. for its support of Israel and sent the U.S. economy into recession.

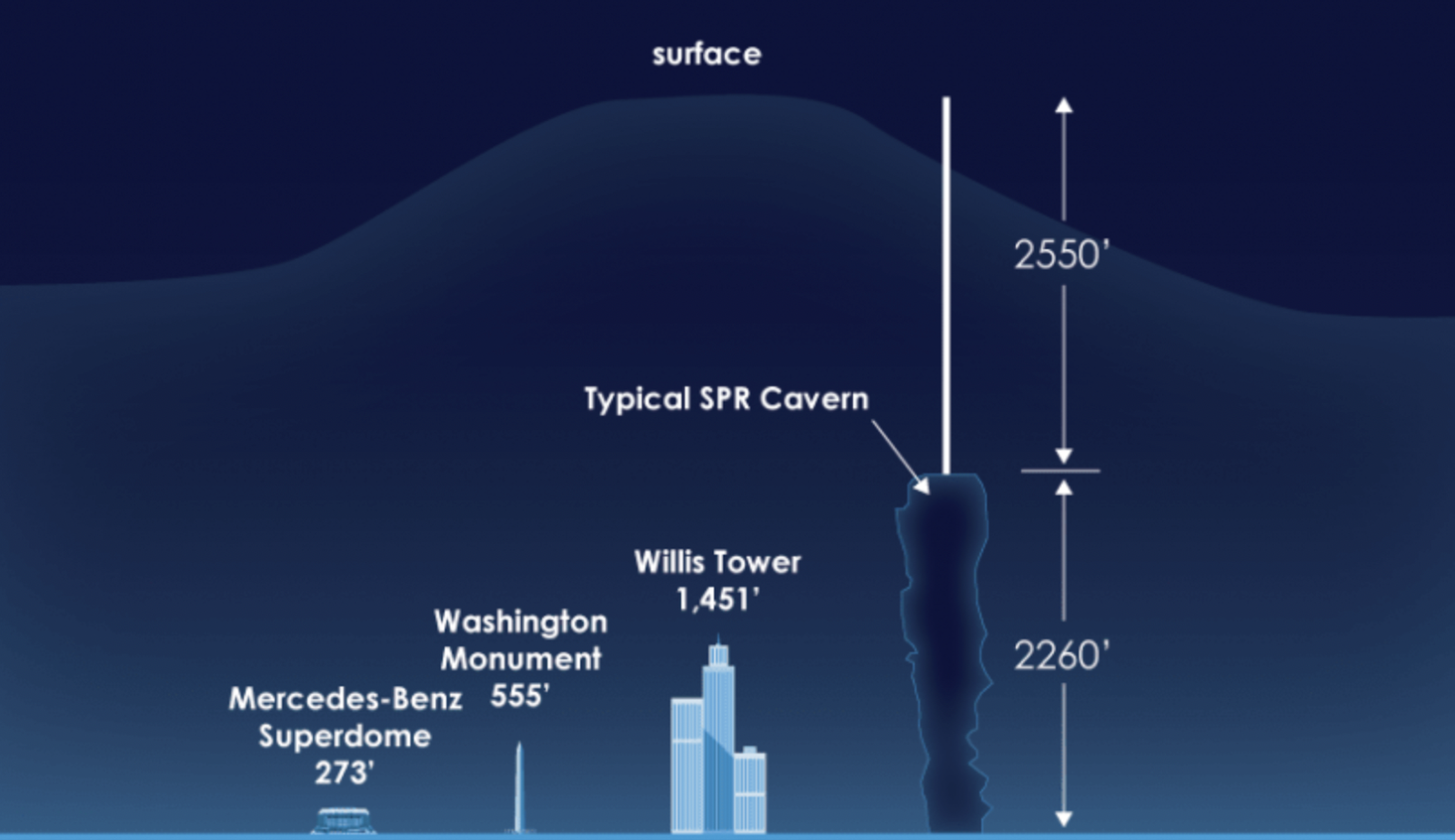

SPR oil is stored in four sites along the Gulf Coast: two in Texas (one in Bryan Mound and one in Big Hill) and two in Louisiana (West Hackberry and Bayou Choctaw). The entire reserve is stored in 60 underground salt caverns, which on average are 200 feet in diameter and 2,550 feet tall. Using salt caverns rather than a normal surface oil tank is safer and cheaper, according to the Department of Energy.

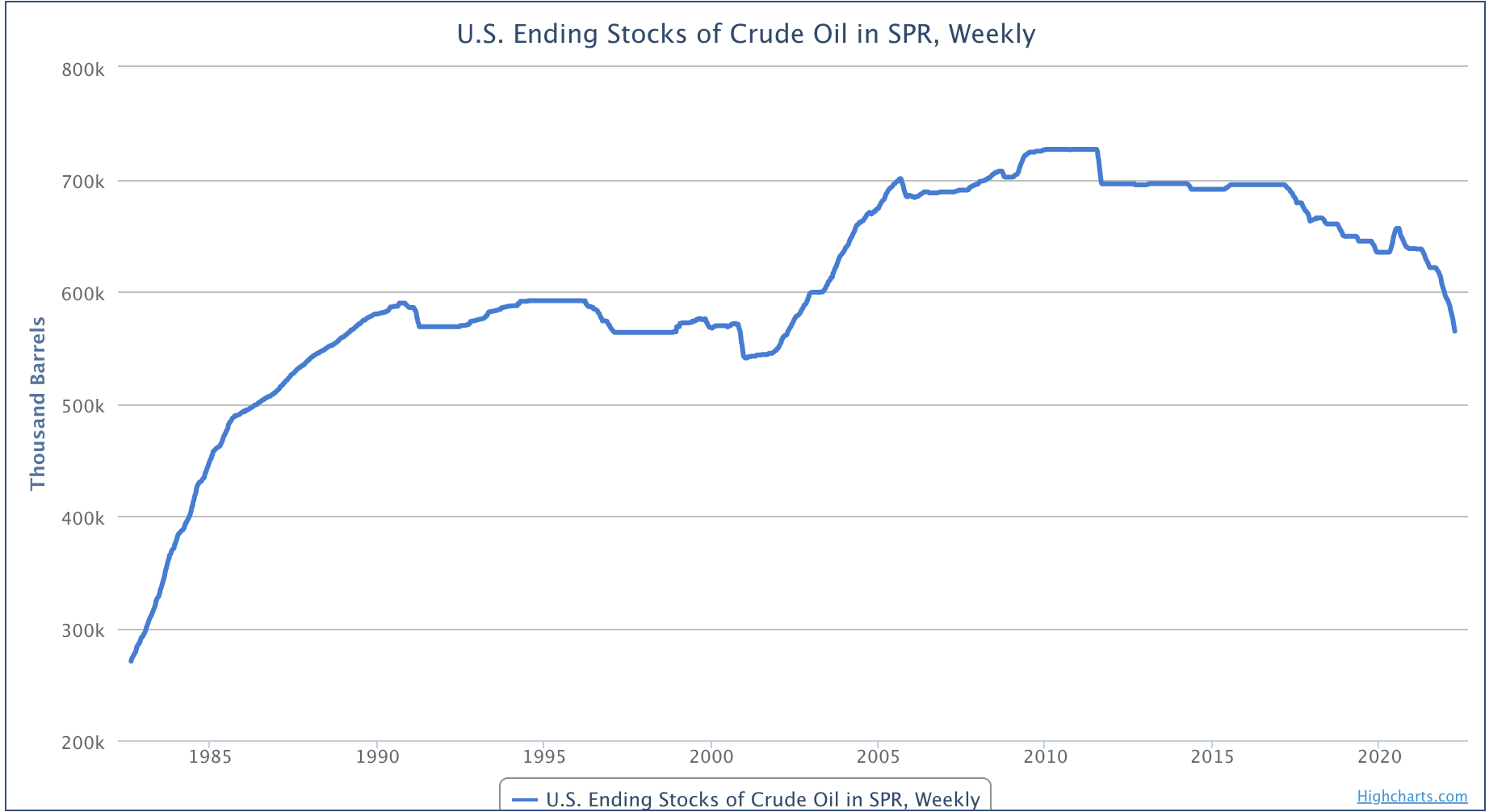

The amount of crude oil in the SPR has fluctuated since its inception. As of March 31, the SPR had 570 million barrels of crude oil in stock (enough to power the U.S. economy for about 28 days). The stockpile maxed out at nearly 730 million barrels under President Barack Obama and then has been slowly drawn down ever since.

There are two main categories for oil drawdowns from the SPR: sales and exchanges. An exchange is a temporary loan of crude oil. In an emergency, such as a hurricane, an oil company may ask for oil from the SPR with the understanding that it will return the same or better quality oil within the terms set out in a contract with the Department of Energy. The U.S. often requires companies to pay back “premium barrels”—essentially interest payments in the form of extra oil.

Biden’s plan this time around is to sell the barrels of oil to companies. The government will award contracts to bidding oil companies, then ship the oil to refineries, where it’ll be processed for the market.

The SPR’s location on the Gulf Coast allows the government to distribute crude oil to most of the country quickly. Using preexisting pipelines and barges, the SPR can distribute oil to nearly half of the oil refineries in the U.S.

The storage facilities are always “drawdown ready,” meaning the Department of Energy can disburse oil within 13 days.

Drawdowns happen fairly often, GasBuddy analyst Patrick De Haan told The Dispatch. Different sales include congressionally mandated sales (usually to generate revenue for the federal government), test drawdowns (done to make sure the SPR is ready in case of an emergency), non-emergency sales, and emergency sales. According to the Department of Energy website, there have been 28 drawdowns since the SPR’s creation.

The government’s goal is to sell crude oil at a high price, then buy more to restock the reserve when prices are low. And that seems to be the goal of the Biden administration, De Haan said: “The thinking is agreed upon that oil prices will continue to cool off. U.S. oil production will continue to increase slowly in the months ahead. So it does seem to be a pretty sure bet: Sell high and then buy low down the road.”

According to the White House, the money made from selling the oil now will be used to restock the SPR “in future years.” (Each administration decides how much oil to keep in reserve.)

So will this historic drawdown have an impact on the price of gas?

“The impact on energy may vary,” De Haan said. “It depends because there’s a lot of potential offsetting news. Oil prices did react by falling on the announcement, but keep in mind that a million barrels a day is relatively small compared to the discussion that’s still ongoing between European countries on the potential to sanction Russian energy, which would basically halt the flow of four and a half million barrels of oil change to the EU.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.