The coverage of the vote for House speaker set to take place in five weeks is beyond obsessive. But it’s easy to understand why.

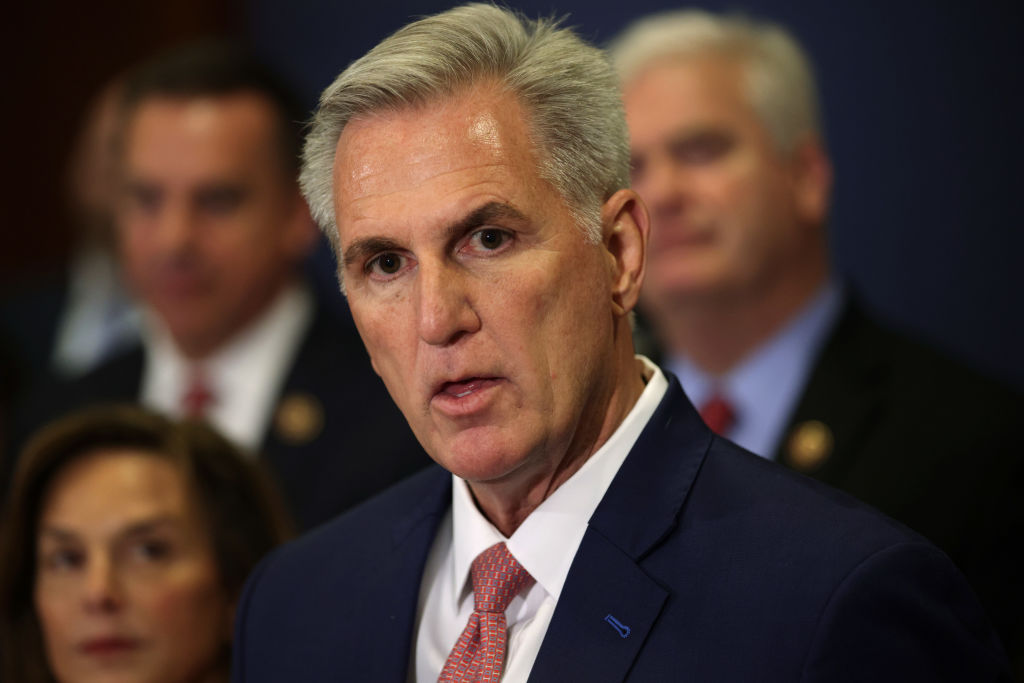

Rep. Kevin McCarthy is a figure of something between contempt and disgust for almost all Democrats and some Republicans. The bipartisan consensus against McCarthy creates lots of appetite for stories about his desperate pandering, strategy around the vote, the disaster scenarios for the California Republican, and, most intriguing for the left, the possibility that the radical Republicans who are so enjoying torturing McCarthy could overplay their hand and end up tipping control of the gavel to a moderate.

The Republican House majority is probably going to end up being only five seats deep. The GOP has won in 220 districts, and leads—barely—in the last two contests that still aren’t called as of this writing. That means that McCarthy will only be able to afford, at most, four defections and still get the 218 votes he needs to become speaker when the new Congress convenes. Given the 31 MAGA members who sided against him in the internal party vote for leadership posts and their subsequent taunting, it’s impossible to see right now how McCarthy wins on the first ballot. For context, when Paul Ryan cruised to the speakership in 2015, nine out of 245 Republicans voted against him. The GOP caucus is much smaller and more radical than it was then.

Beyond the political interests of Democrats and pro-Trump Republicans like those in the House Freedom Caucus, there’s another reason that the first vote of the 118th Congress on January 3 is getting such excessive coverage: It’s just good copy. McCarthy is a Shakespearian figure. The gossipy details of his failed 2015 bid added intrigue, but it has been his Mark Antony-like contortions in pursuit of power that have made McCarthy such a figure of fascination. What becomes of a man whose need for power leads him to such self-abasement when he finally obtains what he has coveted? What would become of him if he failed again?

It’s got everything you’d need for a House of Cards script with enough practical implications to make political addicts all sit a little closer to the edge of their seats. But how that vote goes and what happens to the political narrative going into the 2024 presidential nominating contests will depend on two other votes that happen before McCarthy meets his fate.

Georgia Grind

In eight days, Georgia will again be the center of the political universe with the runoff election between Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock and his Republican challenger, Herschel Walker. The outcome on December 6 is hardly certain. There’s been only one useful public poll released so far, and it shows Warnock with a 4-point advantage. That tracks with the first round of voting on November 8, when Warnock beat Walker by a point, but the Libertarian candidate drew more than 2 percent of votes. With control of the Senate already decided by the Republican fizzles elsewhere, there’s no additional motivation for right-leaning voters who couldn’t stomach Walker to vote for him now. And since voters had to be registered before the general election to be eligible to vote in the runoff, the electorate can’t really grow.

On the other hand, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, who got 202,861 more votes than Walker out of some 4 million ballots cast, has, for the first time, campaigned with the Senate nominee. And turnout is something of an open question. In 2020-21, when Warnock won both rounds over incumbent Sen. Kelly Loeffler, turnout declined only 9 percent from the general to the runoff. But it wouldn’t be unusual to see a far steeper decline, like the 43 percent decrease in Georgia’s 2008 Senate runoff. And just as Republicans and right-leaning independents don’t have Senate control to think about when reassessing Walker, neither do Democrats when it comes to rallying turnout for Warnock. So, you’d have to say Warnock is favored to win, but only slightly.

While the results may not determine control of the Senate, they will have something to say about how the members of both parties perceive the results of the midterms and the current state of play. If Walker does indeed go down, the hardening narrative that Trumpism is a loser for the GOP will be further set. Former President Donald Trump invested more into Walker’s candidacy than any other of his preferred Senate nominees. And while Trump-backed candidates won in Ohio and North Carolina, MAGA nominees who Trump helped to primary wins were defeated in every other battleground race: New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Nevada. If Walker adds to that number, it will reinforce the growing sense among Republicans that Trump’s conspiratorial kookism is unaffordable. If Walker rallies to win, however, Trump will have a valuable counterargument to the case against his leadership of the party.

The unpopular former president is so far doing the right thing for his protégée and staying out of Georgia, but what if Trump’s nemesis, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, decides to cross the border and stump for Walker? Could Trump stay away then? Outcome and process will both matter for a Republican Party going through a wrenching internal dispute.

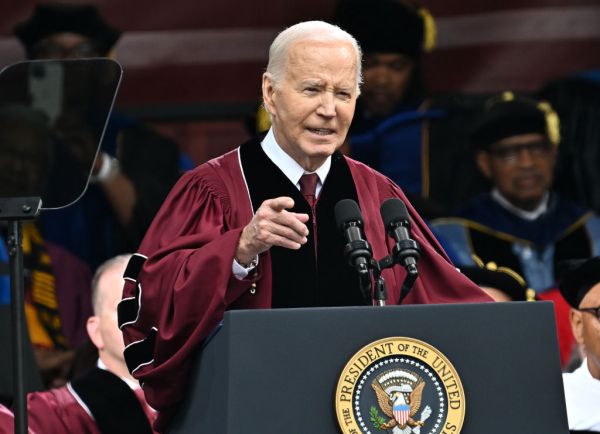

On the Democratic side, a Warnock win would similarly reaffirm the existing narrative that President Biden has got mojo coming out of midterms. Plus, a 51-seat majority would give the president some breathing room in future negotiations with Sen. Joe Manchin and other moderate Democrats looking to hold up legislation. A Warnock loss, however, would come as more of a surprise to Democrats than it should and would be a sour note on which to end a midterm cycle that was an unexpected relief for the Democratic establishment.

Hitting the Ceiling

The other big day that will help shape McCarthy’s chances and the political climate beyond is just 10 days after the Georgia vote, when the government hits its next fiscal cliff as the current spending package expires on December 16. The main question is how long the lame-duck Congress will give the incoming one before having to try to pass another extension with a divided government.

The last time Republicans had a House majority with a Democratic president, government shutdowns and jousting over the federal debt ceiling were mainstays, and Republicans seem to be gearing up for the same this time around. But next month, the outgoing Democratic-held Congress will get to decide how soon that will happen.

Without an increase to the federal borrowing limit, the government is on track to max out its credit line some time in the first part of next year. If the current Congress doesn’t goose that number and delivers only a stopgap funding measure, the late winter and spring of 2023 could be a real disaster. Congressional Republicans want Democrats to do all the heavy lifting while they still control both Houses, but GOPers do want to have their say on spending priorities. Democrats, on the other hand, don’t want to have to include Republican considerations if they’re not getting a considerable number of Republican votes.

Now, put yourself in McCarthy’s shoes. In his remaining weeks as minority leader, he will be obliged to take the hardest line possible against any Democratic spending proposals. That won’t be a problem … unless outgoing House Speaker Nancy Pelosi loses any more than three Democratic votes on the final passage of any spending plan. And there are lots of radical Democrats who for ideological or political reasons might like to act like their counterparts in the Freedom Caucus and scuttle a close vote. That could mean Pelosi needing Republican votes, which means either more moderation or a much shorter time horizon on the deal.

It would be good for McCarthy as speaker to have a long-term spending and debt deal in place when he takes the gavel. But if he is seen as trying to produce that outcome, it will further jeopardize his chances to get the radicals to vote for him on January 3. Democrats also have reasons to not want a fiscal disaster in 2023, including the knowledge that Biden would also pay a price and that the blue team’s bargaining position on priorities will be decreased in the House minority. But right now, Republicans are the ones with more need for a deal but less flexibility in reaching one.

How voters in Georgia and the members of the lame-duck Congress behave next month will have a great deal to say about how the speakership vote goes, but also how the parties see themselves as the next presidential cycle begins. It’s going to be a busy December.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.