Over the last few months, we’ve seen President Trump do an uneasy dance with the public health experts running his government’s pandemic response. All of his political instincts—his instinctive suspicion of the sort of establishment eggheads who people the health bureaucracy, his constant attentiveness to right-wing media, his tendency to put branding and sloganeering over concern for the facts—pushed him toward picking a fight with his pandemic experts along the lines of his years-long squabble with the intelligence community over Russian election interference. But the incredible gravity of the pandemic partially stayed his hand: After an early period of downplaying and dismissing the virus, President Trump shifted in early March, beginning with a primetime Oval Office speech that essentially functioned as a PSA for good virus-fighting hygiene.

In the months since, Trump has teetered between these two poles: Offering staid and informative briefings on the status of federal pandemic efforts one day, boosting wild conspiracies about the virus and thumbing his nose at his own doctors online the next.

Recently, however, that balance has tipped more and more away from Trump humoring the experts and toward Trump indulging his instincts. In this regard, Wednesday may have been an inflection point.

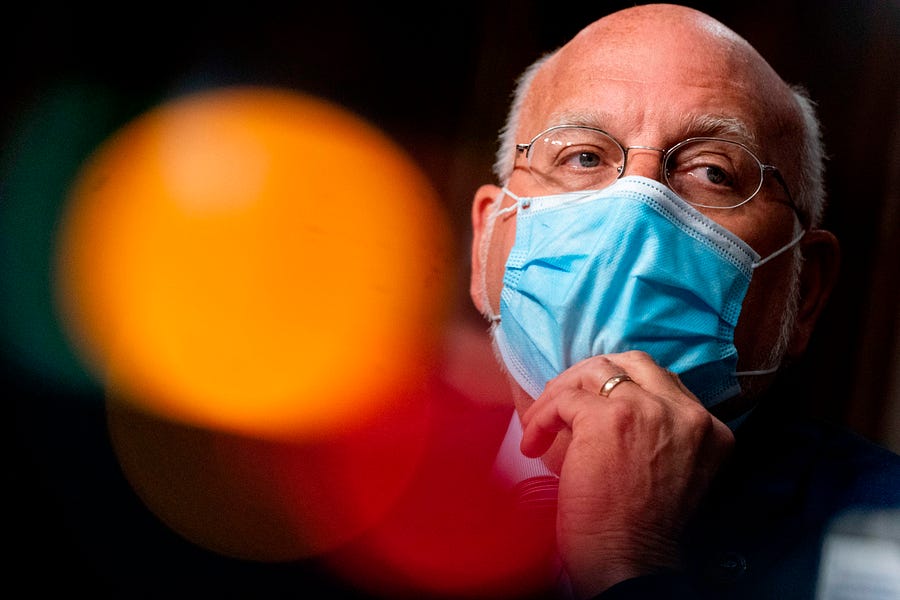

The pandemic news day began somewhat innocuously, with routine congressional testimony by CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield on a COVID vaccine, including a discussion about its timing and distribution. The White House had been pushing an aggressive vaccine timeline, which had led many of the president’s critics to fret that Trump might lean on his government to approve a vaccine before the November election, whether it was proven to be safe and effective or not. But others thought these concerns were overblown: After all, the experts themselves had been saying that having a vaccine approved within just a few months was not outside the realm of possibility.

Redfield’s testimony was straightforward: A vaccine is coming and should be on the ground soon, but we will need time to scale its production for widespread national use.

“If you’re asking me when is it going to be generally available to the American public, so we can begin to take advantage of the vaccine to get back to our regular life, I think we’re probably looking at late second quarter, third quarter 2021,” Redfield said.

This was consistent with what we’ve been hearing from other experts in the know for weeks: Earlier this month, Dr. Moncef Slaoui, the head of the White House’s “Operation Warp Speed” vaccine task force, told NPR that while we may have enough vaccine by the end of 2020 to immunize “between 20 and 25 million people,” getting the vaccine out in sufficient quantities to immunize the U.S. population would take “until the middle of 2021.”

But now enter the president. At a press briefing later in the day, Trump made a strikingly more aggressive claim: “As soon as the FDA approves the vaccine—and as you know, we’re very close to that—we’ll be able to distribute at least 100 million vaccine doses by the end of 2020 and a large number much sooner than that.”

A reporter asked Trump to clarify—didn’t that contradict what Dr. Redfield had just told Congress in sworn testimony?

“No, I think he made a mistake when he said that,” Trump replied. “It’s just incorrect information. … Maybe it was stated incorrectly.”

Later in the evening, a spokesperson for Dr. Redfield put out a statement trying to soothe the messaging rupture: “In today’s hearing, Dr. Redfield was answering a question he thought was in regard to the time period in which all Americans would have completed their COVID vaccination, and his estimate was by the second or third quarter of 2021. He was not referring to the time period when COVID-19 vaccine doses would be made available to all Americans.”

Then, about an hour later, the CDC retracted that statement, telling reporters not to use it. In the space of 12 hours, we’d moved from a relatively consistent, government-wide message on the likeliest timeline for the rollout of a vaccine to a total meltdown of communication on this crucial question.

These sorts of messaging trainwrecks matter. Trying to get important public health information through to the public is a tricky business in the best of times; people just have too many pressing things going on in their lives to spend hours sifting through competing public health narratives to try to get at the truth. Instead, they tend to retreat into partisan information silos, or to tune the conversation out altogether.

Scientists are particularly worried about this phenomenon when it comes to the coming COVID vaccine. Over the summer, public eagerness for such a vaccine diminished: More than a third of Americans now say they would not get the vaccine today even if it were free and FDA-approved, according to a recent Gallup poll.

That’s an alarming figure taken on its own, but it’s made more alarming by the fact that we don’t yet know how effective the COVID vaccine will be. While some vaccines do a good job fully immunizing every recipient against the targeted disease, others, like the seasonal flu vaccine, only reduce a person’s risk of becoming sick. That’s usually still enough to hammer a pandemic, provided everyone gets the vaccine: Even though not everyone is perfectly protected, the population as a whole has gotten virus-resistant enough to stop pathogenic spread in its tracks. (This post-vaccination phenomenon is ordinarily what we have in mind when we talk about “herd immunity.”)

If a substantial portion of the population declines to get vaccinated, that picture gets far messier.

“If the COVID vaccine is not highly effective, if we start giving it to a bunch of people and a lot of those people still get sick, that’s going to hurt our ability to get a high proportion of people vaccinated,” Dr. Megan Ranney, an emergency physician and professor at Brown University, told The Dispatch on Tuesday, prior to this whole messaging snafu. “So how do we deal with that? Well, it requires coherent and consistent public messaging from people across government.”

Trump’s comments on the vaccine timeline and his slapdown of Redfield weren’t the most explosive comments of his Wednesday presser: That distinction probably goes to his partisan assessment of his virus response, waving aside America’s nearly 200,000 coronavirus deaths on the grounds that “If you take the blue states out, we’re on a level that I don’t think anybody in the world would be at.” But if the president’s willingness to throw a top pandemic official under the bus is any indication of what’s to come between now and the rollout of the vaccine, we might be in for a longer, rougher ride than we thought.

Photograph by Anrew Harnik/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.