I am no defender of comic book movies and TV shows, especially those from Marvel. While entertaining, they can be a bit empty and have grown bland over time. I’d planned never to watch another Marvel property again after Avengers: Endgame, but then along came WandaVision. I was intrigued.

For those familiar with the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the show’s premise and early episodes feel like a major departure. Marvel has devoted entire films to telling a particular character’s origin story, but opens WandaVision by dropping two Avengers into a strange place and the wrong decade without explanation. The movies take superheroes on quests to dark corners of outer space, but the show is confined to a small town in New Jersey.

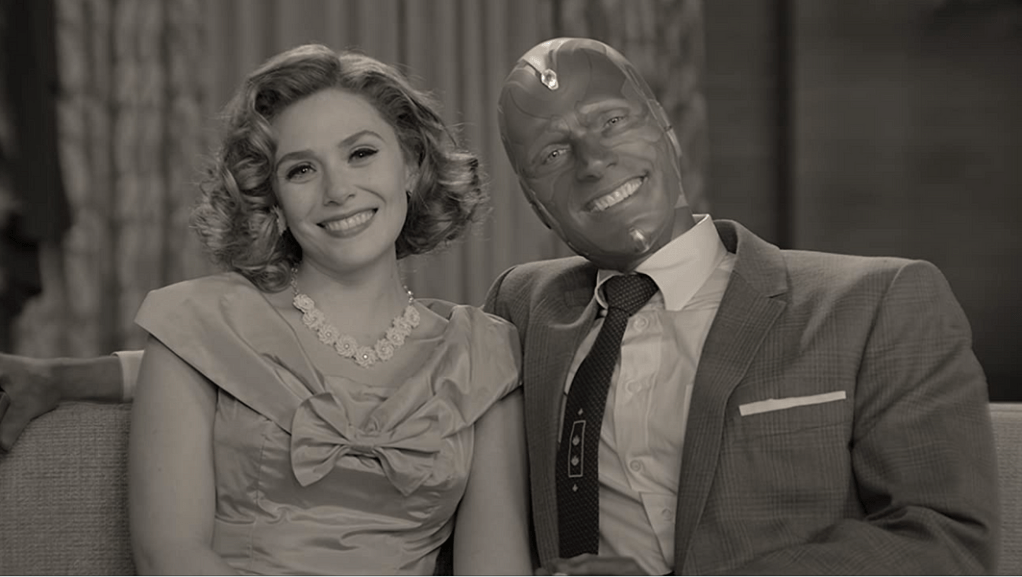

The movies are action flicks full of explosions and battles. But in WandaVision’s first episode, viewers are treated to a 1950s-era sitcom starring Wanda Maximoff (Elizabeth Olsen) and Vision (Paul Bettany). Wait, what? Wanda, a sorceress with superpowers, and Vision, an AI android whose body is made of vibranium, both came to the MCU in Avengers: Age of Ultron. They later fell in love. But (spoiler alert!) Vision died in Endgame, so what is he doing alive and well in the 1950s with Wanda and a boring desk job?

At first, it seems like even Wanda and Vision aren’t quite sure. They fail at polite small talk when dinner guests ask benign questions about their past. They know they are different—Wanda cheekily signals to Vision to transform from his android self to a human on his way out the door, and we see that even superpowers can’t help her in the kitchen—but the early episodes present no context as to why they are in living in a small town, in the past, or why time keeps jumping.

The second episode is set in the 1960s, and as time advances, the illusion starts to falter. In her grief Wanda has, in ways she doesn’t understand, brought Vision back to life and transformed a small town in New Jersey into an idyllic sitcom setting where they can play house. But the viewer starts to understand there is more to the series: Strange objects and people appear, and we learn just how closed off the town of Westview is.

This is, perhaps, the most mature entry in the MCU canon, with Wanda’s grief and the domestic life of Wanda and Vision serving as the focus of the show, while some vague recurring eeriness eventually turns into full-blown mystery. The show does away with the typical trappings of a superhero movie, even eschewing a cut-and-dried heroes-and-villains template—viewers don’t learn the identity of the “big bad” until the seventh episode in the nine-episode season. And while we’re meant to find Wanda sympathetic, she’s clearly not a hero anymore: She somehow kidnapped an entire town and is forcibly controlling its residents’ minds to make them play along with her fantasy.

While the show is entertaining and even compelling at times, it does still give way to the corporate world-building that has come to define the MCU. There is plenty of fan service and nods to the comics, and, especially in the later episodes, the show’s focus on its own storyline strays.

There has been much discussion about the “implications” of various creative decisions about the show, which serves to set up the Dr. Strange sequel: how a casting decision offers a peek into the the Marvel multiverse, how one character seemingly acquiring superpowers could be a prelude to her own possible movies, how the focus on magic could mean magical Marvel properties will join the MCU, how a subtle retcon is setting up the X-Men. WandaVision is not allowed to be a property in and of itself, it must still tie into and pave the way for other Marvel properties.

While WandaVision manages to be an intriguing show, it’s also a deeply frustrating one. It serves as a subtle reminder that pop culture can be more than what we’ve experienced the past few years, and a not-so-subtle reminder of how franchise-building can pervert the art of cinema. Had this been a self-contained show, where the writers weren’t constrained by the past of the MCU and forced to plan for its future, how would the show have been different? It’s a testament to the strength of the creative team members behind WandaVision that they make the show work as well as it does, even with Disney forcing them into a creative corner. I suspect that with more freedom the show would have been even better.

WandaVision does show that audiences can and do appreciate complexity in what they watch, that they don’t need big spectacle and empty CGI fight scenes to stay invested. Maybe—hopefully—studios will start to realize that such depth can be appreciated without a superhero veneer.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.