We often hear that what this country needs is an honest conversation about race.

Here’s a whole lot of “honesty” for you, from an unexpected place:

Black people are less likely than white people to be self-reliant.

Black people are less likely to emphasize “rational linear” and “quantitative” thinking.

They are less likely to think that “hard work is the key to success.”

They believe in punctuality less, and instant gratification more, than white people. Black people aren’t as likely to believe in a Christian god and are more inclined to be tolerant of pagan or multi-god religions.

Given that we are living in the age of “cancel culture,” I’d better explain what I’m doing lest anyone think I believe this nonsense.

All of this stuff—the bigotry, the stereotypes and the outright falsehoods—isn’t my view. Nor did I get it from some white supremacist website.

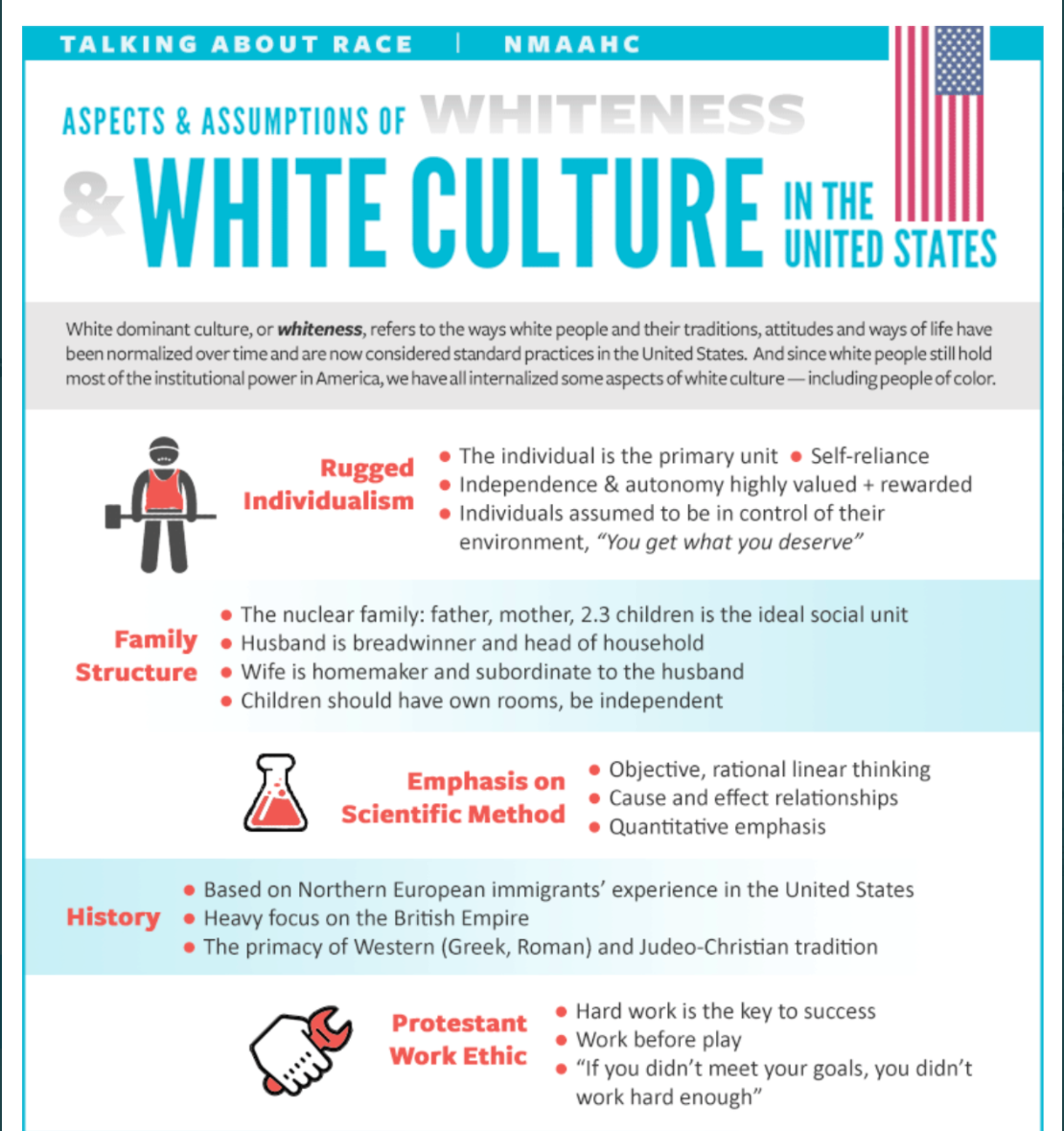

Nope, it comes from a graphic sourced and linked to by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The museum’s website has a whole “Talking About Race” section. An article on “whiteness” cites a graphic titled “Aspects and Assumptions of Whiteness and White Culture in the United States.”

Much of the stuff from the graphic can be read as an insult to black people if one simply assumes that black people believe in these things less than white people. For instance, with the graphic indicating that whiteness and white culture are defined by “respect for authority,” an appreciation for “delayed gratification,” the tendency to “follow rigid time schedules” and the belief that “hard work is the key to success,” the implication is that black people are less defined by these values.

I’m pretty sure I’d be called a racist if I were to take my cues from this list and say, “Unlike white people, black people don’t believe that hard work is the key to success.”

Some of the other race-based assertions from 30-year-old research by Judith Katz, a white diversity consultant, aren’t merely bigoted by implication, they’re just wrong, or at least misleading. Sure, “Christianity is the norm” for white Americans (though less so every year). But do you know who it’s even more of a norm for? Black Americans. And Hispanic Americans.

According to the Pew Research Center, blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to attend church—Christian church—regularly. As for the notion that whites are disproportionately biased against multi-god faiths, I can’t find any evidence for it. Indeed, from what I can tell, most forms of paganism and polytheism in America tend to be almost exclusively white phenomena, though data here is pretty hard to come by.

There’s a lot in this that makes me angry, but the worst thing is that this garbage is almost designed to make race relations worse. For instance, Katz’s cheat sheet informs us that a defining norm of white communication is the notion that one should “be polite.”

First, I only wish that were more true of white culture. But more importantly, what in the world is this woman talking about? Are good manners not a valuable norm for everybody? After all, manners are simply modes of conduct to show others respect. Good manners and mutual respect reduce the chances for conflict, including violent conflict, in every society — which is why every society has norms of politeness. Is that really just a white norm that we need less of today? Should white people, in order to shed their privilege, be less polite to anyone? To black people? To immigrants?

If I were to say to a black friend, never mind a black stranger or co-worker, “Look, I understand your culture doesn’t value punctuality or hard work the way mine does …” would that be better? It would certainly be impolite to say the least.

This nonsense works on the assumption that mainstream, bourgeois norms—hard work, delayed gratification, punctuality, etc.—have no intrinsic or extrinsic value separate and apart from white culture and white privilege. That’s not only insane, it’s harmful, because it gives people permission to reject these norms as “structures of oppression” or some similar balderdash.

Why on earth would you want to tell black people such a thing? Why would you want to tell anybody this stuff, even if it were true?

I’m all for changing any norms of politeness that make black Americans (or Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, et al.) feel oppressed or excluded. But I can’t fathom how putting these ideas into action helps do anything of the sort.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.