Just as parents shouldn’t play favorites with their children, a Trump critic shouldn’t play favorites with his indictments. They’re all special in their own way.

But if we’re being honest, there’s a pecking order.

The first indictment, charging Trump with falsifying business records related to the hush money paid to Stormy Daniels, is the problem child. This one might make something of itself in the long run, but it’s not very bright and no one’s expecting much from it. It’s a troublemaker.

The second indictment, charging Trump with concealing classified documents, is the dependable child. It’s no-nonsense, straightforward, and rock solid, the child you leave in charge when you have to run errands. If anyone’s going to deliver a conviction, it’s this kid.

The third indictment, charging Trump with crimes related to trying to overturn the 2020 election, is the ambitious child. This one means well and has big aspirations. It might very well go on to great things. But it risks biting off more than it can chew. Expect spectacular success—or spectacular failure.

The fourth indictment, handed down on Monday night for election tampering in Georgia, is the favorite child.

The favorite child is the one that’s most like you, that sees the world as you do. It doesn’t get held to the same standards as the other three. There’s a special connection.

The special connection between the Georgia indictment and Trump’s critics is that it recognizes his attempt to overturn the 2020 election was a conspiracy with many accomplices.

Eighteen people besides the man himself were charged in Fulton County. “This is basically a RICO indictment of the Republican Party. As it should be,” former Republican strategist Stuart Stevens tweeted afterward. “Every Republican elected official who refused to acknowledge the winner of the 2020 election is an unindicted co-conspirator.”

I agree. There are no “Trump problems” in the GOP, I’ve said before, only problems with lackeys and voters facilitating his most corrupt impulses. Georgia’s indictment is the first to reflect it. (Charges may yet be filed against the likes of John Eastman and Jeffrey Clark in the January 6 matter.) Whether Trump’s campaign was, as the document alleges, a “criminal enterprise” within the meaning of the law in January 2021 is for a jury to decide. But it was plainly a corrupt scheme with many willing participants—a racket, in short.

To see this lifelong shyster, forever babbling about “loyalty” and “rats” like a common mafioso, finally be accused of a classic mob crime like racketeering is gratifying in a way that the other indictments aren’t. Convicting Trump for concealing classified information would be nice but only in a getting-Capone-on-tax-evasion way. Convicting him in the January 6 case would be nicer but would still land awkwardly, as charges like “obstructing a congressional proceeding” don’t capture the magnitude of what he did.

Racketeering is true to the essence of the man. It’s morally, not just legally, correct. And, importantly, it captures the breadth of corruption within the party to a degree that no other indictment does.

There are also prosaic reasons to treat the Georgia indictment like a favorite child.

Because it’s a state prosecution, a newly reelected President Trump won’t be able to pardon his way out of jeopardy or to order the proceedings shut down. Because the evidence of wrongdoing against him is stronger than it is in Manhattan, there’s less chance that the case will fall apart under its own weight. Because there are umpteen co-defendants, he’s at risk of his cronies flipping on him to help put him away.

Inevitably he’ll try to pressure Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp into granting him clemency. But that ploy, which would succeed in practically any other state governed by a Republican, will fail here. In Georgia, the power to pardon belongs to a state board, not to Kemp, and the qualifications for eligibility are strict. Even if the matter were left to the governor, I wouldn’t expect Kemp to issue a get-out-of-jail-free card. On Tuesday morning, Kemp posted this tweet responding to Trump’s promise of evidence to come of voter fraud in Georgia:

There are few politicians left in the Republican Party who owe Trump nothing. Kemp is one, having routed his hand-picked challenger in last year’s gubernatorial primary. There are no favors to call in to make this one go away.

Trump’s best bet for avoiding a conviction is to run for president successfully and then sue Georgia to have the prosecution suspended while he serves out his term, arguing that to go forward would damage the United States by interrupting the executive branch’s ability to function. His odds of winning on that point are quite good, I suspect. But as the electorate comes to understand that reelecting him would amount to nothing less than placing him above the law in four separate jurisdictions, his chances of victory should—knock on wood—shrink.

There are less prosaic reasons to treat the Georgia indictment like a favorite child. Like this: The racket is ongoing.

By “the racket,” I don’t just mean Trump’s effort to prove that the election was rigged—although that’s ongoing as well, almost three years later, as Kemp’s tweet demonstrates. I mean the enablers across the GOP, top to bottom, who continue to insist in shrill and increasingly desperate ways that he shouldn’t face accountability for anything he’s done from anyone. That includes voters: What else was “Stop the Steal,” after all, if not a partywide scheme to end his accountability to the electorate?

A few examples. Last night, a former Supreme Court clerk, turned state solicitor general, turned U.S. senator—who’s been touted as a future justice—was reduced to ranting about a legal document before he’d read it. Ted Cruz delivered this stemwinder on Fox News an hour before the indictment was released.

It’s true that not until recently had a former president ever been indicted. It’s also true that not until recently had a president ever organized a racket to overturn a national election. Extraordinary corruption may inspire extraordinary prosecutions. For Cruz, however, this matter appears straightforward: By his logic, any credible candidate running for office should be immune from criminal jeopardy. (A handy position for a once and future presidential candidate to hold.) I invite readers to judge for themselves what sort of behavioral incentives a rule like that would create. Would it lead to more criminals getting involved in politics or fewer?

Another alleged lawyer, Lindsey Graham, took a different approach. Let the voters sort this out, Graham pleaded on (where else?) Fox News.

Jonah Goldberg has complained repeatedly on Dispatch podcasts lately about Trump apologists moving the goalposts on how to deal with his malfeasance. In February 2021, when it looked like the Senate might convict and disqualify him, some Republicans argued there was no need. The criminal justice system would handle him. Now that the criminal justice system is handling him, flunkies like Graham insist there’s no need. The voters will handle him.

The problem is that if the voters do handle him by sending him down to defeat next fall, Trump and most of his party will screech that he was defrauded at the polls again. That will inspire a new rigged-election racket, which will inspire more criminal activity, which will inspire more prosecutions, which will inspire future teary Lindsey Graham appearances on Fox News pleading with the public to let voters decide the matter in—deep breath—2028.

So the racket never ends. Voters can’t end it because their verdict will never be accepted as legitimate if it comes out the wrong way. Congress can’t end it because too many Republicans in the House and Senate are either zombified Trump loyalists who won’t convict him on principle or cowards afraid of losing their seats. The criminal justice system can’t end it because any charges, however meritorious, are dismissed out of hand by the likes of Lindsey Graham as politicized and destructive to the civic fabric. Accountability in any forum is impossible, by design.

This thinking isn’t exclusive to Trump toadies. Here’s “good Republican” Tim Scott, who twice voted to acquit him in the Senate, greeting the Georgia indictment today by grousing about the politicization of law enforcement.

I’d like to believe Scott would accept a Trump defeat next fall as the legitimate verdict of the voters, but I’d also like to believe Scott would refuse to be Trump’s running mate since to accept would be tantamount to ratifying his earlier putsch attempt. But I don’t believe the latter, so I don’t particularly believe the former.

If the “good Republican” isn’t already done with Trump after January 6, criminal charges or not, he’s in on the racket too.

No one outside of Trump’s inner circle has participated in the racket as enthusiastically as grassroots Republicans. Wittingly or not.

The polls are enough to prove it, in particular the surge Trump enjoyed after the first indictment in late March. FiveThirtyEight notes how his favorable rating among Republicans actually improved following that episode and remains on par today with where it was in January of this year. As of Tuesday afternoon, his lead in the RealClearPolitics national average is a whisker shy of 40 points, his biggest of the campaign.

At best, the “indictment effect” has cost him nothing in the primary. At worst, it’s created a rally-around-the-accused-felon dynamic that appears to have sewn up the nomination for him.

“Any time you have a pack of dogs chasing you down and you’re willing to stand firm and fight, you’re going to get my vote,” one Trump supporter recently told the New York Times. “DeSantis doesn’t have a pack of dogs hunting him down, and that tells me that somebody’s probably backing him, or he’s in somebody’s pocket at this point.” Can’t argue with logic as airtight as that.

Trump himself half-joked about the indictment effect in a recent campaign appearance:

I’m game for a fifth indictment, to help him really lock down Republican voters. But four is almost certainly enough.

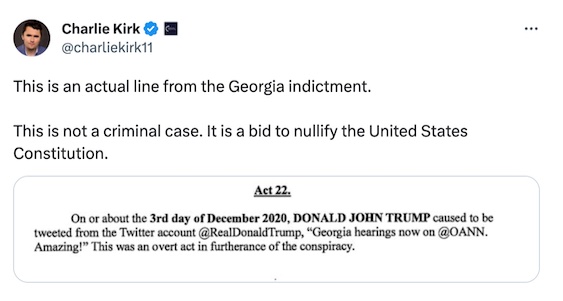

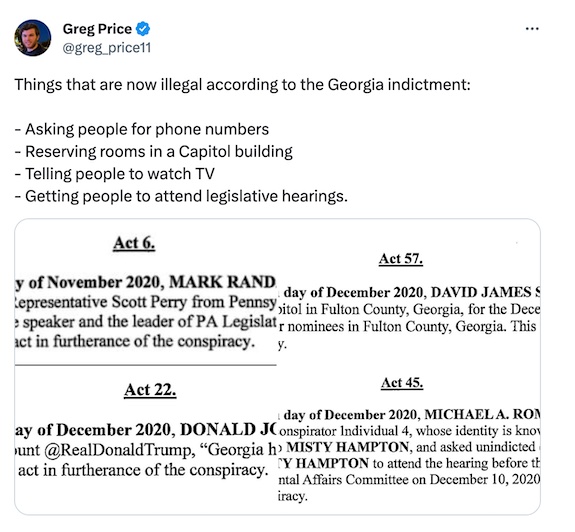

As the felony charges pile up, pro-Trump activists have been forced to get creative in conjuring new explanations for why he shouldn’t be held accountable. Whether those explanations are products of desperation, earnest stupidity, or a contemptuous belief that their MAGA audiences will swallow anything is unclear and interesting but ultimately irrelevant. Just drink in the sort of reasoning one needs to accept to believe that something untoward is afoot in the Georgia indictment:

When FBI agents searched Mar-a-Lago for missing classified documents last year, outraged MAGA pundits denounced it as a “raid” and claimed that if they could do it to him, they could do it to you. When those same pundits discovered that January 6 detainees faced hard conditions in jail in D.C., they were aghast at their treatment. Now they’ve discovered that perfectly legal behavior can create criminal liability in certain circumstances.

It leaves me to wonder if any of these people paid the slightest bit of attention to how the criminal justice system operates before their political heroes ran afoul of it.

Jail is unpleasant in every jurisdiction in the country. The FBI “raids” homes by executing search warrants all day every day across America. (They did it to Trump because they do it to you.) The law of conspiracy, which is what Trump is charged with in Georgia, has always criminalized “overt acts” that are legal in themselves if they’re undertaken to carry out an unlawful plot. It’s kind of the point of RICO statutes. As one attorney put it, mocking the indignation of people like Charlie Kirk, “so suddenly it’s a crime to buy a plane ticket with ten of your best friends on 9/11?”

This possibly deliberate, possibly sincere obtuseness among his loudest fans about the nature of the racket Trump is running would be bad in isolation. Much worse is that it’s happening while he’s publicly trying to intimidate witnesses, lawyers, and judges in the proceedings against him on his social media accounts. For all the comparisons between Trump and mob figures, not even the mob dares to confront the justice system as brazenly as that. If you worry earnestly about politics corrupting law enforcement, as Charlie Kirk claims to do, you should probably spare a thought about a quasi-gang leader treating court officers as political enemies.

Charlie does not appear worried.

Maybe he’s in on the racket because he’s dim or because he’s greedy. Maybe he yearns earnestly to be ruled by a right-wing authoritarian and is willing to make excuses as necessary toward that end. Who knows why he or anyone like him is in on it? But they are. Which, again, is why Georgia’s indictment is the most righteous of the four: It recognizes that culpability for Trump’s behavior extends far beyond the man himself.

I’ll leave you with three thoughts, each cheerier than the last.

One: Trump being Trump, I suspect that at some point he’ll simply stop cooperating with the machinery of the law as it turns against him. He’ll blow off a court appearance or ignore a judge’s order and dare law enforcement to do something about it. Let them try to drag him out of Mar-a-Lago and see what happens. Or see if Gov. Ron DeSantis will assist in an extradition request from another state. However things end, they won’t end well.

Two: One can’t overstate how terrible the personnel in a second Trump White House would be. He was already scraping the bottom of the barrel by the end of his first term; now that a number of his cronies have been indicted in Georgia, including former chief of staff Mark Meadows, only the most fanatic sociopathic droogs will be willing to risk working for him going forward and being entangled by future criminal rackets. So that’s who he’ll end up with. I hope the Senate is prepared to use its constitutional prerogative to keep as many of those people out of government as possible.

Three: Jack Goldsmith is surely right about some of the “terrible consequences” that will flow from prosecuting Trump. In particular:

It will probably inspire ever more aggressive tit-for-tat investigations of presidential actions in office by future Congresses and by administrations of the opposing party, to the detriment of sound government.

It may also exacerbate the criminalization of politics. The indictment alleges that Mr. Trump lied and manipulated people and institutions in trying to shape law and politics in his favor. Exaggeration and truth shading in the facilitation of self-serving legal arguments or attacks on political opponents have always been commonplace in Washington. These practices will probably be disputed in the language of, and amid demands for, special counsels, indictments and grand juries.

Joe Biden is likely to be impeached this fall by the Republican House, possibly meritoriously, possibly not. Either way, that’ll be the third presidential impeachment in four years and the fourth in 25 years; in the 200+ years of American history before that, we had one.

Tit-for-tat is real.

Similarly, soon Republican prosecutors will feel pressure to answer the meritorious prosecutions of Trump with criminal prosecutions of prominent Democrats—possibly meritorious, possibly not. When it happens, I ask only that we remember where the blame for this bold new frontier in civic disintegration ultimately lies. Hint: Not with Jack Smith or Fani Willis. “Once Republicans nominated a political mobster, it was close to inevitable the U.S. would be crossing a perilous threshold,” Damon Linker observed this morning. The right refused to hold its immensely corrupt leader accountable in any way, then made Democrats choose between letting him operate above the law and starting a tit-for-tat game of retaliatory political prosecutions. The choice has been made. Don’t lose sight of who forced it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.