Dear Capitolisters,

With much of Washington on August vacation and after digging deep in the last few (dozen) newsletters, now’s a perfect time to explore a non-policy issue that—much like nachos—deserves more attention: exclamation points. Indeed, while the so-called “media” devote infinite words to the relatively recent problem of price inflation, the longer-term scourge of Americans’ skyrocketing exclamation point usage—aka “exclamation inflation”—has gone unnoticed by all but the most observant and socially conscious of writers and grammarians.

This, as we’ll discuss today, is a costly mistake.

(And for those of you jonesing for more traditional Capitolism content, fear not: There will be charts here too.)

A Brief History of the Exclamation Point

Before we get to today’s myriad exclamation point problems, however, let’s first review how we got here. Believe it or not, the exclamation point’s history isn’t well-settled, but Wikipedia provides the most common origin story:

Graphically, the exclamation mark is represented by variations on the theme of a full stop point with a vertical line above. One theory of its origin posits derivation from a Latin exclamation of joy, namely io, analogous to “hurray”; copyists wrote the Latin word io at the end of a sentence, to indicate expression of joy. Over time, the i moved above the o; that o first became smaller, and (with time) a dot.

The exclamation mark was first introduced into English printing in the 15th century to show emphasis, and was called the “sign of admiration or exclamation” or the “note of admiration” until the mid-17th century; “admiration” referred to that word’s Latin-language sense, of wonderment.

The folks at How Stuff Works then bring us up to modern day:

While exclamation marks have long been scorned in formal writing, throughout the centuries people regularly used them in personal correspondence. And in the late 19th century, yellow journalists and sensationalists often incorporated the startling marks—which printers called screamers, shrieks or bangs—into their work.

During the 20th century, use of the exclamation point calmed down. In fact, while the typewriter was invented in the late 1800s, the exclamation point wasn’t given its own key until 1970. The reason was people weren’t expected to use it in professional writing. An exclamation point was created by typing a period, backspacing, then typing an apostrophe on top of it.

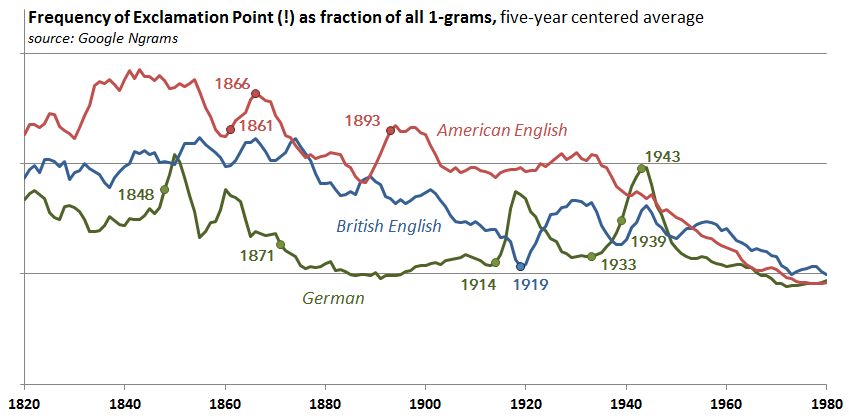

These 19th and 20th century trends are corroborated by Bradd Libby’s analysis of the number of times the exclamation point appears as a fraction of single words (“1-grams”) in Google Books data for various languages:

Libby notes in the accompanying post that the 1970s flatline continued in the 1980s and 1990s. Then, as How Stuff Works explains, something happened: “[A]round the end of the 20th century, when the internet and texting became widespread (followed by social media a decade later), exclamation points began popping up everywhere, and in great numbers.”

Boy, did they.

The social media and email push toward ever-increasing exclamation point abuse has been confirmed in several recent reports, as well as by literally anyone with an email or social media account. Things like “Hi!” or “Thanks!” are now standard fare—the latter so commonplace, in fact, that it’s frequently in automatic email signatures. (A permanent state of online excitement? Sounds exhausting.) However, as Seinfeld presciently noted way back in 1993—and as hilariously documented by the sadly defunct blog Excessive Exclamation—this verbal violence hasn’t been isolated to the online world:

And, naturally, it often accompanies other grammatical disasters:

An exclaiming emoji? Come on.

Why Not?

So why oppose exclamation inflation? Isn’t it a harmless way to show happiness or appreciation, especially to online friends and colleagues who might need some emotional support?

Hardly.

First and most basically, most of today’s exclamation point usage is grammatically incorrect. As the authoritative Grammarly notes (emphasis mine):

Periods go at the end of declarative sentences, question marks go at the end of interrogative sentences, and exclamation points go at the end of exclamatory sentences. An exclamatory sentence is one that expresses a strong or forceful emotion, such as anger, surprise, or joy.

No offense to my co-workers (among others), but I do not have “forceful emotion” when acknowledging receipt of your last round of document edits or your scheduling request. I’m thankful, sure, but it didn’t make my week. A simple period, at most, is therefore sufficient.

Second, and more importantly, exclamation abuse inevitably dilutes the punctuation’s efficacy over time. Some defenders claim that an exclamation point conveys “sincerity,” but that’s only true when it’s unique or interesting to the recipient. Once a single mark becomes ubiquitous, it’s meaningless: Does your colleague’s single mark mean he actually is happy to receive your message (or whatever) or is he just performing the new bare minimum (and does he maybe even secretly hate you)? As The Atlantic’s Julie Beck noted in 2018, many people at that time (which is like 20 years ago in Internet Time) already assumed that one exclamation point is insufficiently enthusiastic. Surely, more do today.

Numbing readers with endless exclamation points not only undermines the punctuation’s utility (as well as the utility of any words to which it’s attached), but also will demand additional exclamation points in the future, thus threatening an endless upward spiral of exclamation point usage. Now that the single exclamation point is standard, for example, writers will feel the need to use two exclamation points to ensure their readers deem them sufficiently enthusiastic. In a few years, three exclamation points will be needed; then four; then five; and so on.

Indeed, according to my own personal projections*, the acceleration of exclamation point usage in the mid-2000s—surely fueled by both the contemporaneous creation of Twitter/Facebook and early millennials’ entry into the workforce around the same time—has become exponential, threatening a more-than-sixfold increase of total exclamation point usage through 2050:

That’s simply unsustainable.

Third, exclamation point abuse can harm not only annoyed curmudgeon recipients like me, but also the punctuation perpetrators themselves. For example, the continuous distortion of an exclamation point’s value (see Point 2 above) has been found to inflict an emotional toll on correspondents forced to determine—via unwritten rules likely developed and distributed by a secret cadre of too-online millennials and zoomers—the “proper” number of exclamation points needed to convey their message (and, importantly, to not offend their recipients). As Beck notes, this burden is particularly heavy for women:

The pressure to use exclamation points can sometimes feel stifling—a trap [Georgetown linguistics professor Deborah] Tannen calls “enthusiasm constraint.” The belts on this particular straitjacket are tighter for women, as many studies have shown; exclamation points can be a sort of emotional labor women have to perform to be liked, especially in the workplace

How Stuff Works notes additional harms for the eternal exclaimers:

In the business world, people who use a lot of exclamation points in messages are more likely to be seen as underlings than supervisors, according to at least one study. And when it comes to posting negative online reviews, using too many exclamation points causes people to discredit your review—unless you’re an expert in the subject matter, according to another study.

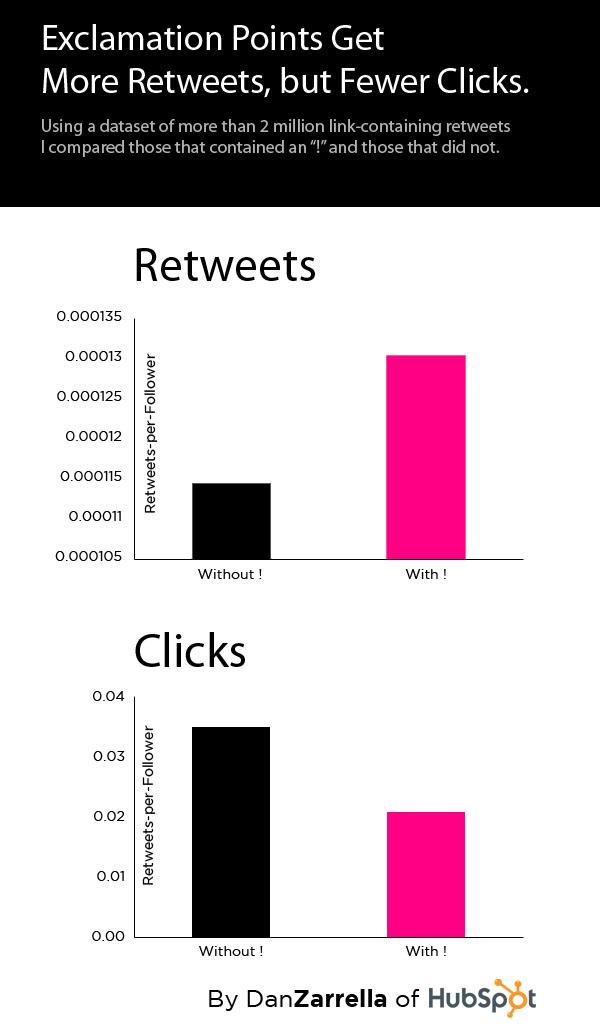

Social marketing scientist Dan Zarella has found, moreover, that exclamation points used on Twitter encourage retweets but discourage people from actually clicking on the information you’ve provided—reinforcing the conclusion that overuse diminishes your credibility:

(But, hey, at least you got those sweet, sweet retweet endorphins, right?)

Exclamation point usage might also harm your social life: “a ghostwriter for those struggling on dating apps claims that if you want to find your soulmate, you need to avoid exclamation points because they convey an overly enthusiastic greeting.” Thus, exclamation points appear to be the “overly-attached girlfriend” meme of the online dating world.

Yikes.

Exclamation point abuse might even be a tool of national propaganda. We can all have a laugh at a certain former president’s rampant abuse of the exclamation point on Twitter (sad!), but Libby’s research shows a more nefarious political history:

We can also actually see the rising usage of exclamation points in German text from 1933 right through the end of the war. So, while historians pin the start of World War II to Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, from Hitler’s perspective it seems to have started right from the moment he came to power.

He therefore concludes that “the Nazis created a wave of sensationalism, they didn’t just ride one to power”—and the exclamation point was their wave machine.

Sad, indeed.

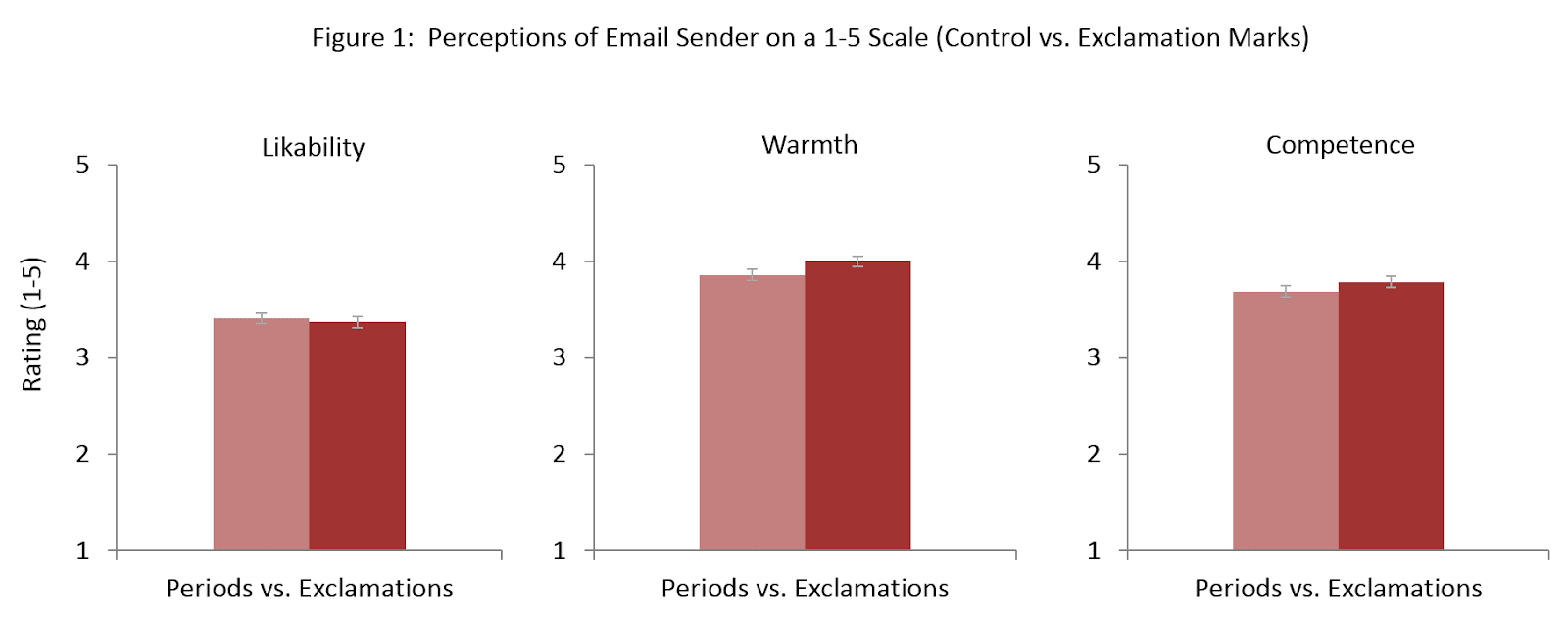

Finally, exclamation points are almost always unnecessary. One recent study shows, for example, that the punctuation carries little emotional value: “it really doesn’t matter too much whether or not you use exclamation marks in emails.” Those researchers sent 400 people a hypothetical email that either contained exclamation points or just periods and commas. They found “no effect of exclamation mark usage on likability of the email sender … nor perceived competence of the email sender…, and a very small effect on perceived warmth”:

Thus, contrary to what you might think, the only one who seems to care about using an exclamation point is you, the sender, not the recipient of that email you’re obsessing over. (Pretty self-absorbed, if you ask me.)

As Grammarly notes, moreover, there’s an easy replacement for all those silly symbols—actual words:

Instead of relying on exclamation points to convey your urgency or excitement, use more vivid vocabulary. Instead of “Make sure you finish this by tomorrow morning!” try “It’s crucial that you finish this before tomorrow morning’s deadline.”

Even in word-limited social media, there are plenty of alternatives to an exclamation point: emojis, all-caps, or—again—just better words.

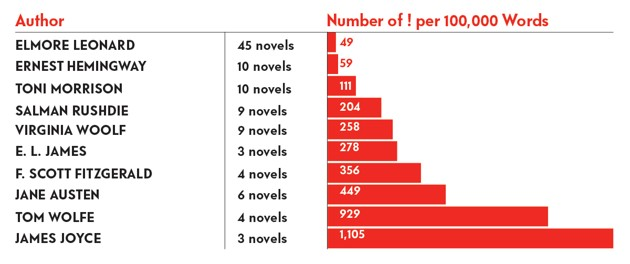

Given this reality, exclamation points are essentially a literary crutch—for both the hypersensitive and those lacking sufficient vocabulary (or too lazy to expand it). No surprise, then, that the world’s most prolific literary giants used exclamation points the least:

Given that exclamation point overreliance can discourage writers from learning and using new words to convey sufficient and accurate emotion, it denies them and their readers of essential knowledge. Combine this “vocabulary deflation” with exclamation inflation, and pretty soon all Americans could correspond via little more than a series of monosyllabic grunts, each followed by no fewer than 73 exclamation points. Ugh.

So, When Should You Exclaim?

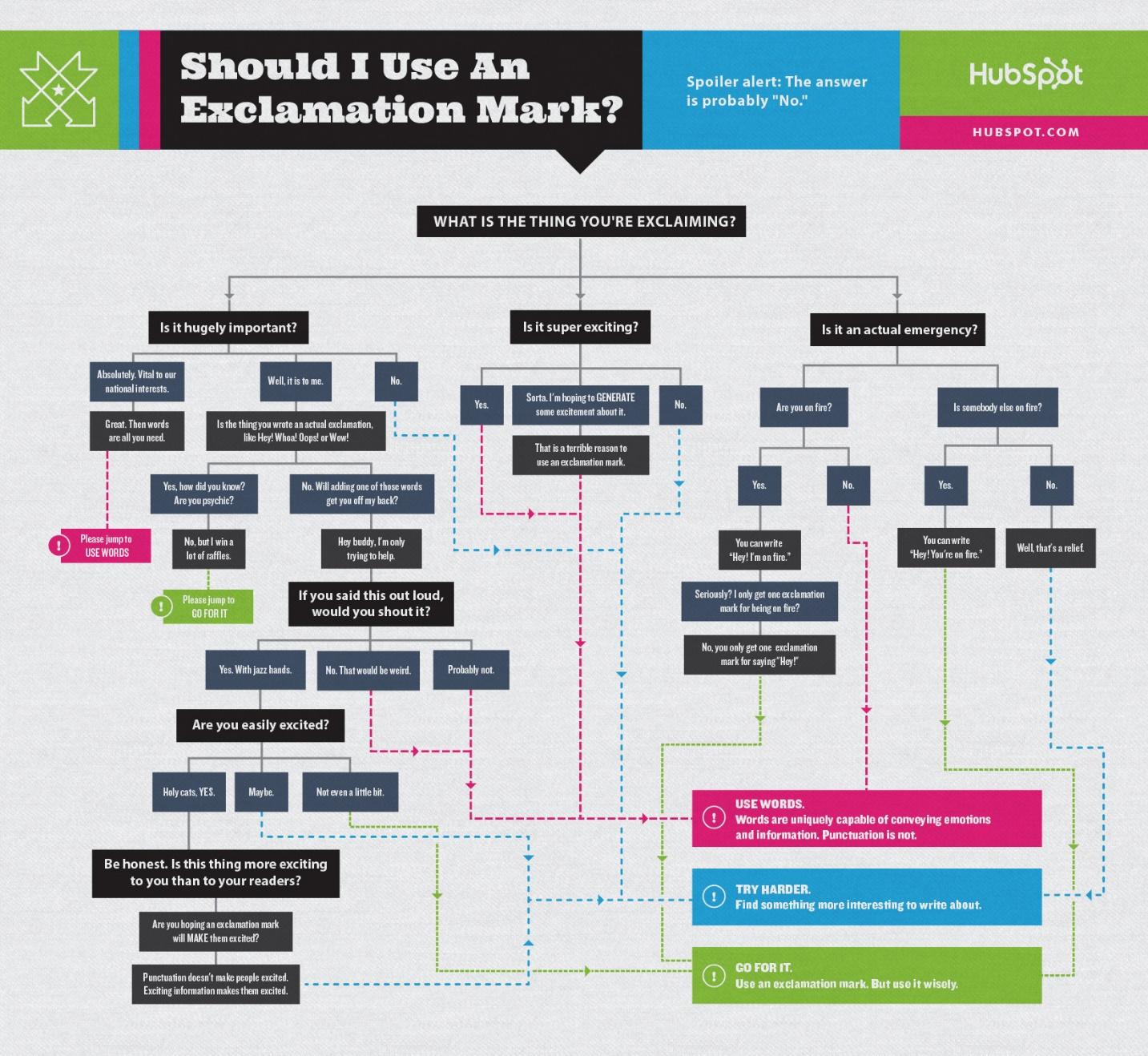

Of course, this doesn’t mean that one should never use an exclamation point. There is indeed a proper time and place for expressing “strong or forceful emotion”—like, say, when you’re on fire. For those seeking additional guidance, Hubspot’s Beth Dunn has created a useful flowchart (Click the link and zoom in for details):

If that’s perhaps too complicated for you, then here’s another useful guide:

Given these clear rules, the ample alternatives, and the serious risks that inflation exclamation raises, it’s long past time for all Americans to put down that punctuation, pick up a dictionary, and stop worrying so much about what other people think.

Please!

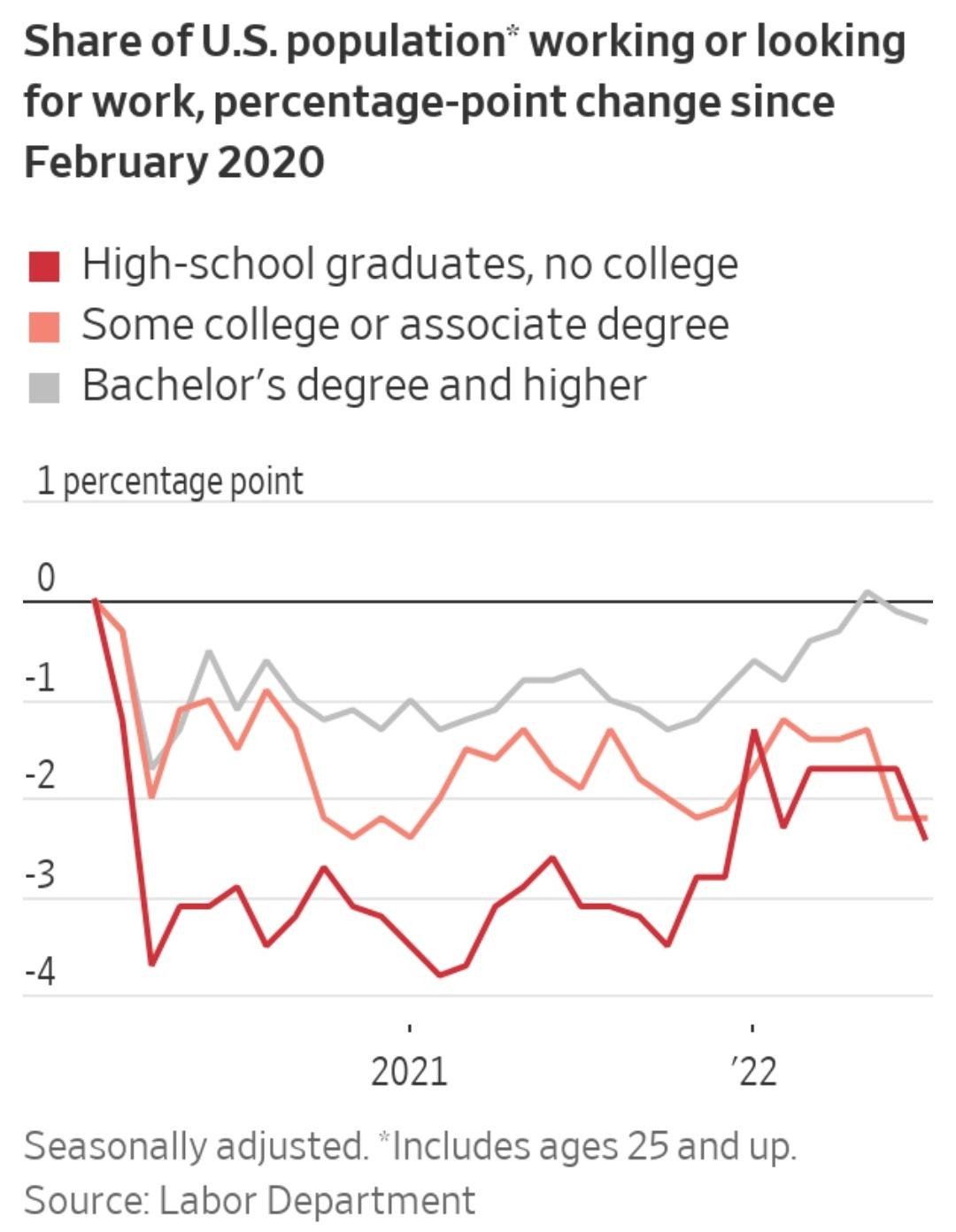

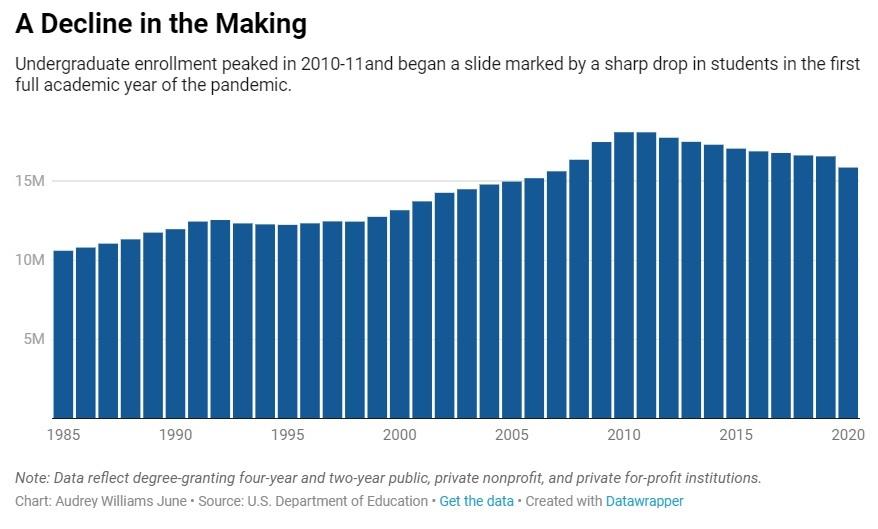

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.