Dear Capitolisters,

One of the United States’ more puzzling and pressing labor force conundrums is the decline in labor force participation among working age adults, especially men. While some—perhaps even much—of this non-participation is benign (attributable to people in school or staying home with kids, for example), a good chunk of it raises real concerns, owed to things like drugs, video games, and welfare programs (especially disability). But a recent CBS news piece hits at another, lesser-covered reason for why many American adults don’t work: They have a criminal record.

Since I covered this issue in my new Cato book and am traveling this week, today’s newsletter will be a lightly edited version of that chapter. Enjoy.

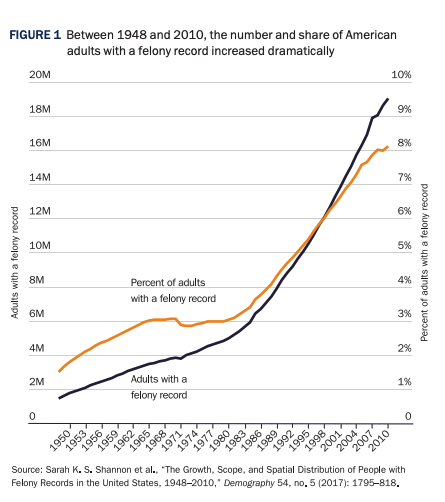

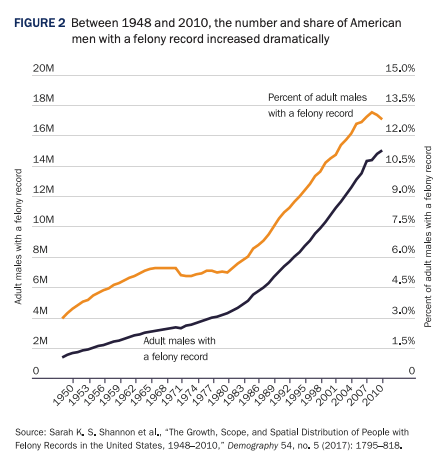

More than 30 percent of American adults have been arrested for a crime, and nearly 8 percent of adults—more than 19 million Americans as of 2010—have a felony record. Employment opportunities are difficult for this population, often due to government policies instead of workers’ ability or willingness to work.

Work is an important step for the reentry and reintegration of those with a criminal history into broader society. It substantially reduces recidivism, particularly in the months after release when reoffending is most likely to occur, and it increases workers’ incomes and economic mobility—outcomes that also benefit the United States as a whole.

Yet employment prospects for those with a criminal record (whether a conviction or merely an arrest) are dim. A study by Shawn Bushway and others for the nonpartisan Rand Corporation estimates that 64 percent of unemployed men in their 30s have been arrested and that 46 percent have been convicted of a crime. Often, the record itself—not the underlying crime—is a significant reason for their unemployment. Meanwhile, the University of Minnesota’s Ryan Larson and colleagues have found a strong connection between an individual’s felony conviction and unemployment or labor force non-participation (especially for women), and that the country’s increasing felony-history share since the 1980s translated to about 1.7 million Americans not working because of their record. Other studies show a similar connection between a criminal record and non-employment.

Criminal records also impair economic mobility: According to a 2010 Pew Charitable Trusts report, for example, formerly incarcerated individuals were twice as likely as those from similar economic backgrounds who had never been incarcerated to remain at the bottom of the income ladder, even 20 years after being released from prison. These employment barriers exist not only for those convicted of crimes but for any individual with a criminal history, including those who were ultimately acquitted.

Surely, not every individual with a criminal record deserves to be free of it and quickly reintegrated into the workforce, but millions of Americans who pose little risk to others are nevertheless shackled by their records. This includes people who were never actually convicted of a crime, those coerced into accepting dubious plea bargains by ambitious prosecutors, those convicted of drug possession, sports gambling, or other activities that have since been legalized, or those with decades-old convictions for nonviolent offenses. For these individuals, there is simply no good reason why a criminal record should burden their employment prospects and social lives, yet state and federal criminal justice policy currently ensures that they are.

Licensing rules exacerbate the employment challenges of those with criminal records. As discussed here repeatedly, licensing requirements generally place heavy financial and other burdens on qualified workers, but they are especially bad for those with a criminal history. For example, many states restrict the ability of people with criminal records to become licensed professionals in certain industries. According to the Institute for Justice, 30 states allow licensing boards to deny an individual a license due to an arrest that ended with an acquittal, and 13 states allow the denial of a license without regard for rehabilitation or later conduct. These restrictions are generally limited to charges related to the occupation being pursued, but five states even permit licensing boards to deny an application based on any felony conviction, even if it is unrelated to the license at hand.

These licensing restrictions increase unemployment and, perversely, recidivism for individuals with a criminal history. According to a 2016 study from Arizona State University, states with many licensing restrictions on individuals with a criminal record saw a nearly 10 percent increase in recidivism rates, while states with fewer licensing restrictions experienced a 4.2 percent decrease in recidivism during that same period. As unemployment and underemployment are highly correlated with reoffending, reducing licensing barriers to those with criminal histories would very likely increase their employment and decrease criminal activity.

A criminal record can also be a barrier to self-employment. For example, applicants to the Small Business Administration’s largest loan programs, the 7(a) and 504 programs, must disclose all criminal records and histories, including any expunged records. Loans are unavailable for those currently incarcerated, on parole or probation, or convicted within the past half year. The programs also require all applicants ever convicted of a felony to undergo an FBI fingerprint check and an SBA individualized character assessment prior to approval. It is unknown how often the SBA denies an application based on the assessment or how often a potential lender stops the application process if these extra steps are necessary for approval. My Cato colleagues and I have generally been critical of the SBA as a wasteful and unnecessary government intervention in the market. But as long as the agency exists, the harms arising from this discrimination should be considered.

Finally, many states deny driver’s licenses to individuals with minor arrest records or unpaid court debts, thus harming their employment prospects. As of 2017, for example, 11 million Americans had a suspended driver’s license due to unpaid court debt; in New Jersey, 91 percent of license suspensions from 2004 to 2018 were for non-driving issues. Federal law, meanwhile, reduces federal transportation funding to states that do not suspend driver’s licenses of individuals convicted of drug offenses.A suspended driver’s license impedes workers’ ability to find employment because they need transportation or because many jobs (e.g., truck/bus drivers, certified nurse assistants, eye care workers, and even deli clerks) require a valid driver’s license. A 2007 New Jersey Department of Transportation survey of the state’s residents found that 42 percent of respondents lost their jobs following a license suspension, with low-income and younger drivers being the most affected. Newly unemployed workers may be unable to repay court debts (meaning a longer license suspension); others may choose to drive illegally and potentially face harsher fines or jail time.

In our current era of labor shortages and increasing concerns about crime, none of this makes any sense.

The Policy Solutions

Fortunately, there are several policy reforms that would improve the employment prospects of many American workers caught up in the criminal justice system, with little to no harm to its overall efficacy or to individuals without criminal records.

First, governments—particularly at the state level—should expand expungement of criminal records, which effectively seals an individual’s record from public view and lets him or her legally answer that he or she does not have a criminal record in, for example, a job interview. (Expunged records are, however, still available to law enforcement.) Because expungement effectively nullifies a criminal record for most aspects of public life, it can improve employment outcomes for recipients. Researchers at the University of Michigan reviewed expungement recipients in Michigan and found that meaningful employment (jobs earning more than $100 per week) increased by 23 percent relative to beneficiaries’ employment prior to expungement and that wage gains increased by a similar amount. These increases were sustained even years after individuals were granted expungement. Moreover, only 3.4 percent of expungement recipients were arrested within two years of being granted expungement—a lower rate, in fact, than the overall arrest rate in Michigan for the general population.

Most states have expungement laws for certain offenses (often misdemeanors or nonviolent felonies) and have procedures in place for obtaining an expungement. However, the process is usually not easy: An eligible individual must wait several years after finishing the initial sentence, must not have any criminal history after finishing the sentence, and must proactively apply to be granted expungement. This last factor is particularly counterproductive, as many potential recipients are unaware of the possibility of expungement, and even if they are aware, they may struggle with the paperwork and other application requirements.

Given these and other issues, the number of expungement beneficiaries is very low despite the procedure’s many benefits. For example, because individuals had to petition the state of Michigan to receive expungement, the researchers found that, at most, 8.8 percent of eligible recipients in their sample of more than 9,000 cases had actually done so five years after gaining eligibility, even though applications were granted 75 percent of the time. Assuming similar percentages applied to the state’s entire eligible population, it would mean that hundreds of thousands of Michiganders lost out on expungement for procedural reasons alone.

To improve these results and help millions of American workers in the process, governments should enact automatic expungement laws for qualified individuals. After a waiting period in which the individual cannot reoffend, records for misdemeanors and certain felonies would be automatically expunged without the necessity of an application. Several states have already implemented these changes, with Pennsylvania leading the way in 2018 and passing a “Clean Slate” law that automatically expunges non-convictions (the individual was either acquitted or charges were dropped), and minor, non-violent convictions after 10 years of good behavior.

In terms of specific reforms, states should enact automatic expungement for misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies after a period of good behavior, as well as immediate expungement for any record in which the result was a non-conviction; expand automatic expungement to those with juvenile records who do not commit future crimes, as Michigan did in 2021; and automatically and immediately expunge the records of all individuals with a history of offenses that are no longer crimes in the state at issue (e.g., expunging possession and distribution charges after a state legalizes marijuana). Several states automatically expunge certain records of marijuana offenses after decriminalization or legalization, but automatic expungement should be expanded to all current and future decriminalized offenses. It also should apply to all eligible recipients, even if the arrests or convictions occurred many decades ago.

Congress should enact similar automatic expungement laws for those with a federal criminal history.

State and federal legislation could still require a waiting period of a few years before criminal convictions are automatically expunged, while applying immediately to individuals not convicted of a crime. Recidivism is most common in the months following release, and those who avoid additional convictions for several years after release are extremely unlikely to reoffend (and thus pose very little risk to prospective employers, landlords, and others). Automatically expunging criminal convictions after a relatively short waiting period is therefore a low-risk, high-reward policy.

Expungement is preferable to “ban the box” policies (BTBs), which prohibit prospective employers from asking about job applicants’ criminal history to increase employment among those with a criminal history. This policy, which is now law in numerous cities and counties and in at least 12 states, as well as for most federal agencies and contractors, was intended to reduce discrimination against individuals with a criminal past and increase employment of those with criminal histories.

However, research, such as this 2020 study from economists Jennifer L. Doleac and Benjamin Hansen, has cast doubt on those hopes, finding that implementing BTBs actually reduced young, low-skilled male black employment by more than 5 percent and that this effect persisted even years after the policy was implemented in a specific locale. Moreover, a recent field experiment of low-skilled job applications found that BTBs significantly reduced the likelihood that black applicants would receive a job interview when compared with identical white applicants. Rather than improve employment outcomes, BTBs unintentionally reduce low-skilled black employment, as employers substitute race and educational attainment as proxies for criminal history.

Policymakers should therefore repeal BTBs and instead embrace expungement. In such a case, the criminal histories of certain individuals, such as recent offenders or those with a history of serious felonies, would still be available, and employers would have less cause to statistically discriminate against certain groups. At the same time, individuals with expunged records would not be known to employers to have a criminal history, thus increasing their chances of finding gainful employment.

Second, states should undertake several reforms to ease occupational licensing burdens on those with criminal records. For starters, states should exclude all non-convictions from a licensing board’s consideration, even if the charges are related to the license in question. Acquittals are essentially a sign of innocence, and it is thus absurd for licensing gatekeepers to consider them “criminal” conduct. Also, criminal records unrelated to the license in question or involving since-legalized activities should be excluded from the licensing board’s consideration, and vague concepts such as “moral turpitude” should be dropped or very narrowly defined. Nor should states allow consideration of out-of-state criminal records in licensing decisions if the offenses in question are not crimes in the state where a license is being requested. Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, for example, recently signed an executive order barring state licensing boards from considering applicants’ out-of-state marijuana-related convictions, as marijuana is now legal in Colorado.

As with expungement, moreover, states should set a waiting period after which licensing boards may not consider convictions in their decisions if the individual has avoided further convictions. And states should allow individuals to appeal their licensing decisions and receive rapid decisions on such appeals.

Third, to the extent the SBA remains in operation, the federal government should cease discriminating against currently law-abiding applicants based on prior criminal history. Thus, as long as the SBA’s loan programs are in operation, the agency should eliminate discretionary and subjective requirements, such as the character assessment, and allow all applicants not currently incarcerated, under indictment, or on probation or parole the same standardized application and approval process as that provided to other applicants.

Fourth, states should repeal laws suspending driver’s licenses for unpaid court fines or debts. By the end of 2021, 18 states had done so; of the remaining 32 states, 18 mandate license suspension for unpaid fines or debts, while 14 leave the decision to a judge’s discretion. If full repeal of such laws is not possible, states should require that courts consider the driver’s ability to pay in determining whether to suspend the license. Congress should also repeal current federal law encouraging states to suspend driver’s licenses for drug convictions, as has been proposed in the Driving for Opportunity Act of 2021.

Finally, broader problems in the U.S. justice system contribute to the employment challenges facing those with criminal histories. Overcriminalization—criminalizing even mundane actions, such as taking a neighbor’s children to the bus stop or serving bar patrons pickle-infused vodka, or issuing harsh sentences for minor offenses, such as sentencing someone to life in prison for selling $20 worth of marijuana—greatly increases both the number of Americans with a criminal record and the number of Americans living behind bars. Indeed, this paper from 2021 shows that non-prosecution of nonviolent misdemeanors substantially reduces offenders’ subsequent criminal activity and that avoiding a criminal record likely drives these results. Yet mere possession of marijuana remains a crime in 19 states and under federal law.

Meanwhile, coercive plea bargaining pressures innocent people to confess to crimes they did not commit, not only increasing the number of convictions but often subjecting individuals to significant time behind bars (and thus remaining out of the labor market). Among minors, pretrial juvenile detention reduces the likelihood of graduating from high school and increases the chances that those minors will commit crimes as an adult. These and other criminal justice policies should be reformed regardless of their effect on the labor market, but such reforms would undoubtedly also improve the employment and advancement prospects of millions of American workers.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.