Dear Capitolisters,

There’s this throwaway line in the movie Spider-Man: Homecoming that has stuck with me for the last few years and seems quite relevant in our current (and depressing) political moment. In the scene, Spider-Man arrives at the Staten Island Ferry to break up an alien-weapons deal between some random bad guy and Vulture, played by Michael Keaton (one of the Best Marvel Villains, by the way, other than Tony Stark, of course). Comic Book Fighting inevitably ensues, and Spidey steals Keaton’s alien gun (just go with it) and it begins to malfunction, at which point Vulture yells:

It’s a pretty great scene, remembered mainly for the gun cutting the ferry in half, which put hundreds of passengers at risk and led to Spider-Man being ostracized by Stark/Iron Man (who, in typical fashion, jumped in to save everyone and take credit for fixing a problem that he created). Very fun, if cliché, stuff.

But that line …

Shortly after the 2012 election (which is about 50 years ago in U.S. political terms), a few politicians and pundits on the right began to push a brand of Republican-aimed policy dubbed “libertarian populism” (aka “free market populism”). The basic idea, as espoused by various lib-poppers, was that serious, free market politicians, pundits, and wonks could seize on the Republican base’s increasing populism and energy, primarily embodied in the Tea Party, by channeling the emotional, anti-elite passion in the furtherance of small-l-libertarian policies that were inherently “populist.” Indeed, freer markets, deregulation, federalism, localism, and the like had been repeatedly and historically found to benefit the “little guy” and disempower both Big Government and Big Business. (Sort of an Anti-Corn Law League and William Graham Sumner for the 21st century.) I fully admit that I was enamored with the idea, as were some prominent Republican politicians who saw the chance to ride the populist wave and use it for political gain by contrasting Lib-Pop’s bottom-up, decentralized approach with the top-down, centralized technocracy embraced by both the dreaded GOP establishment and the Obama administration.

This approach, in retrospect, was misguided. Very, very misguided.

My (our) error was in assuming that—contra the history of numerous populist movements—new American populism could be channeled to advance a coherent, informed policy agenda relatively free from the emotional, conspiratorial, nativist nihilism that plagued past movements, and that the leaders of the movement—politicians, publications, pundits—would stick to the principles they claimed to adore when the base’s emotions disagreed. Recent political events, of course, show how unwise this approach is: Trump and his acolytes lied to millions of people and convinced them that the election was stolen. Cynical subordinates like Sens. Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz believed they could score political points by riding the same populist tiger all the way to the White House. What’s the harm, right?

Well, now we know.

As both Jonah and new arrival Haley Byrd Wilt discussed in their most recent columns, there’s a price to be paid for lying to large swaths of people so as not to disrupt their feelings and thereby keep the political gravy train rolling. After a while, they start to believe the lies (confirmation bias is a helluva drug, after all). As Jonah put it, “treat people like they’re delicate little flowers and they’ll behave that way.”

Jonah and Haley focused on the political/election side of this issue, but the populist right’s “feelings over facts” approach affects policy, too. Some of this stuff predates Trump, but his rise indubitably caused what was bubbling beneath the surface of the right’s populism to engulf the Republican Party.

Today, GOP politicians like Hawley and Cruz—and they’re certainly not alone –routinely discard basic facts in an apparent effort to convince an angry populist base that their problems (real or imagined) stem not from their own actions or complex cultural and macroeconomic forces but from “them”—immigrants, globalists, Big Tech, brunching elites, China, you name it. Hawley’s surely the king of this approach, and examples of his malfeasance abound. As we already discussed last week, he echoed Bernie Sanders when mistakenly blaming Walmart for non-existent wage suppression. He’s also pushed to have the U.S. withdraw from the World Trade Organization, despite evidencing no understanding of what the body does or how its rules actually work. But those positions had the right culprits and critics, and controversy gets clicks. So who cares, right?

Cruz’s devolution has been more depressing, as his pre-conversion record was something most fiscal conservatives could appreciate (even if they didn’t always agree with his stance or tactics). But it’s been no less real. Perhaps the starkest example came in mid-2015 when Cruz wrote an op-ed supporting Trade Promotion Authority (which streamlines congressional consideration of trade agreements and is widely considered innocuous), only to reverse himself weeks later—in a Breitbart piece, of course—once Trump made the legislation toxic among the populist right and conspiracies began to spread that it was, among other ridiculous things, a “backdoor” means of liberalizing U.S. immigration law. (It wasn’t.) Cruz also ditched his past support for immigration to become a hardliner, going so far as to block recent legislation offering asylum to persecuted Hong Kongers on supremely dubious fears of Chinese espionage (along with a lot of bad stats).

Now, look, politicians misleading or following their base is nothing new (and left-populist politicians can be similarly fact-challenged), but the right’s populist groundswell has also been accompanied by a new cadre of pundits and wonks riding the same wave of emotional discontent, with a similar disregard for the underlying facts at issue. So, for example, we’re now told that:

-

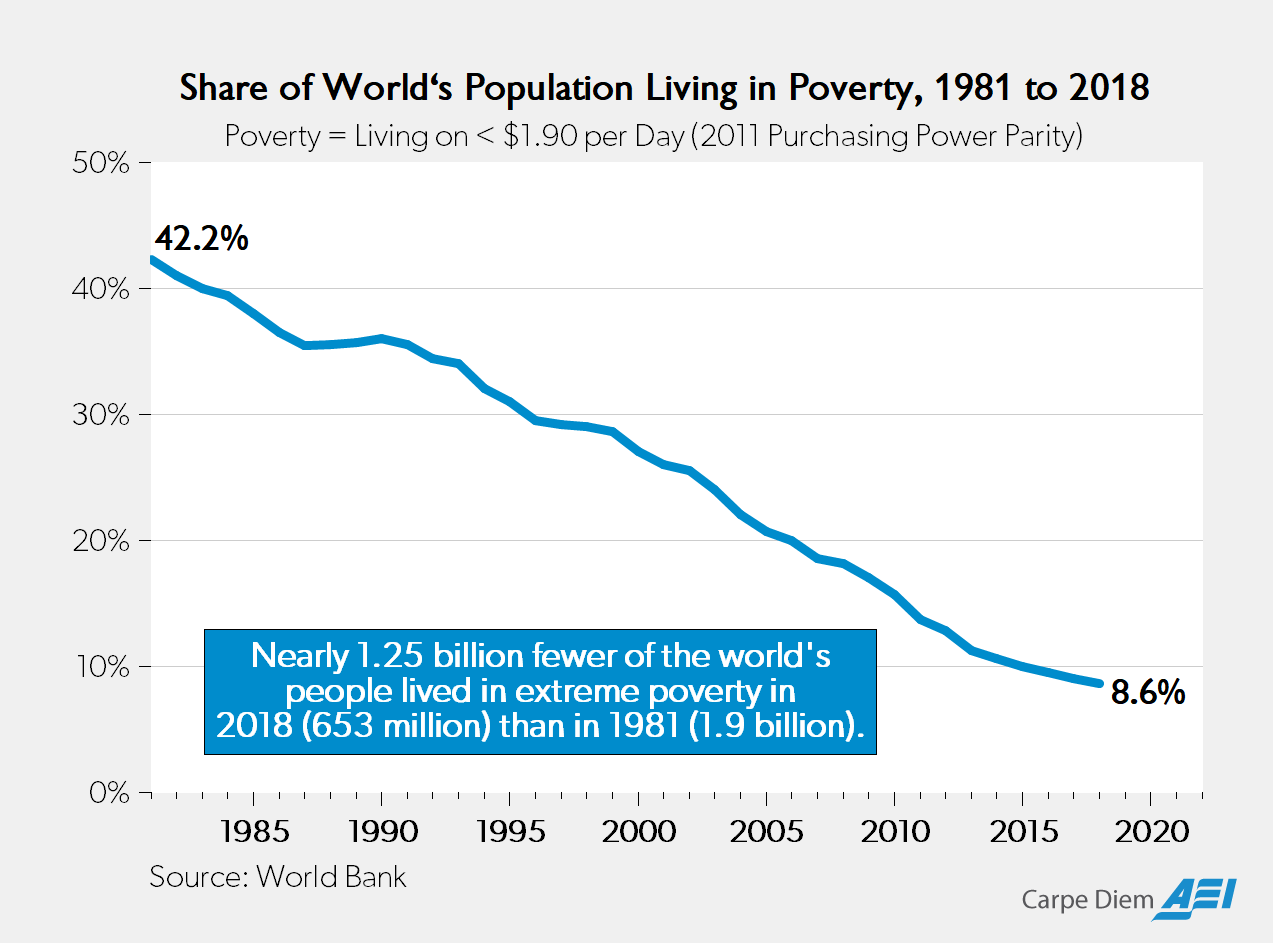

Workers have suffered from decades of wage stagnation and widening inequality despite ample evidence of the opposite.

-

Significant changes to trade and industrial policy are needed to confront American “deindustrialization,” despite the fact that developed economies everywhere are experiencing similar trends and that, in terms of output and financials, the U.S. manufacturing sector is healthy and in many ways globally dominant. (My new paper on this issue will be out in a couple weeks, but you can check these other links if you’re interested.)

-

We can easily have abundant, well-paying manufacturing jobs if we copy U.S. agriculture policy, leaving aside the historic collapse of farm jobs (amid rising output) and the fact that, as I noted a few weeks ago, U.S. farm policy is a costly, corrupt boondoggle that countries like New Zealand and Australia prove is wholly unnecessary.

-

Rampant “financialization” has destroyed the Real Economy, even though financial sector’s share of the U.S. economy has risen only about 1 percentage point since the late 1990s (to about 7 percent) and was actually expanding faster during the halcyon days of the ’70s and ’80s (and in previous two-decade periods that evoke similar nostalgia).

-

Disruptive “globalization” is a new phenomenon created by corporatist (probably libertarian) elites, ignoring that people have been trading internationally for eons (long before modern nation states), and that much of modern trade integration has been driven by technologies like the shipping container, not “trade deals” (which also seem misunderstood).

-

And, of course, heartless libertarians run Washington economic policy, despite the ample evidence to the contrary.

Or there’s Section 230, or immigration, or—of course—tariffs. The list goes on and on. (One could even devote a weekly newsletter to these issues.) Whether out of sincere belief or political expediency, the populist right’s intellectual vanguard often plays fast and loose with the facts, and when they do, it usually reflects or caters to the emotional zeitgeist of the Trumpist moment—heavy on economic pessimism, nativism, and anti-establishmentarian resentment; and unfortunately light on facts, analysis, and history. Of course, not everything these budding policy entrepreneurs say and do is bad, but the willingness to embrace narrative over fact to placate a real (or imagined) base is a hallmark of their movement. And “market fundamentalists” need not apply.

Now, I do not deign to think that populist elites feeding intellectual comfort food to swing voters—whether intentional or not—is the same as Team Trump peddling self-serving election conspiracies to paranoid fanatics marching on the Capitol. But both reflect the movement’s elevation of Populist Truth over actual truth—of feelings over fact. The policy side of this phenomenon, which routinely invents national problems or offers simplistic, ahistorical solutions—protectionism, nativism, industrial policy, etc.—to real ones, fortunately doesn’t lead to violent insurrections, but it does have harmful effects.

For starters, it makes reasoned debate extremely difficult, if not impossible, because that requires at least some basic agreement on the underlying facts and the rules of the debate. If legitimate critiques of, say, Josh Hawley’s specific claims about wage stagnation or the WTO are met with emotional responses—“Okay, fine, but The People don’t feel that way, and oh by the way you’re basically a lobbyist for China”—there’s little point in engaging again. (The New York Times’ Jane Coaston recently called this vague and ever-changing use of the emotional trump card “Feelingsball,” after the Calvin and Hobbes schtick, which is pretty much just perfect.)

More importantly, by placating these feelings and providing a veneer of intellectual support for them, populist elites not only buttress the True Believers but may very well create new and impassioned converts. (There’s ample evidence, for example, that Republicans have been taking their protectionist cues from Trump, not the other way around.) That approach might be good for votes, donations, and book sales, but—to the extent that these feelings aren’t grounded in actual facts, history, law, or economics—it makes governing more difficult in the future when promised policies inevitably fail and an unpersuaded base demands even more unreality (and politicians who will deliver it, good and hard).

That’s not to say, of course, that there isn’t real suffering out there—that there are no cultural or economic problems in America. But serious public policy, not to mention serious governing, requires acknowledging hard truths and complicated realities—no, 1950s manufacturing jobs and lifestyles aren’t coming back; no, ending globalist consumerism won’t restore the American family; and so on—not simply placating the emotional desires (or worse) of a disgruntled base. Populism—on the left and the right, to be clear—makes such seriousness increasingly unwelcome, as it reinforces the worst impulses of an ever-more-impulsive base. Advocates may think they’re being clever or strategic by ignoring the facts and catering to these forces (or they may very well be true believers themselves), but recent events show that they risk losing not only elections, but the electorate itself.

They’re messing with things they don’t understand.

Chart of the Week

Via Mark Perry

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.