Among the now-regular Trump tariff announcements is his plan for eventual “reciprocal tariffs”—a concept championed by the president and his loyal trade adviser Peter Navarro that would, if enacted, set U.S. tariffs on goods from foreign counties at levels approximating the countries’ tariff and nontariff discrimination against American exports of the same products. The idea, repeatedly teased by Trump and officially announced last week, has a certain seductive simplicity: Isn’t it only fair that “we” charge “them” what “they” charge “us,” and that if “they” want duty-free access to “our” market, then “we” should have the same in “theirs”?

Alas, you will be shocked to learn that it is not actually that simple, and that—in the real world—“reciprocal tariffs” would be a catastrophically bad idea for all sorts of reasons, most of which have nothing to do with one’s stance on tariffs, free(ish) trade, or U.S. trade agreements.

Those other concerns have been covered at length—here at Capitolism and elsewhere by trade experts of all stripes—so instead we’ll focus today on the mainly practical reasons why the Trump/Navarro plan for reciprocal tariffs makes little sense.

(And that’s being kind.)

An Administrative Nightmare

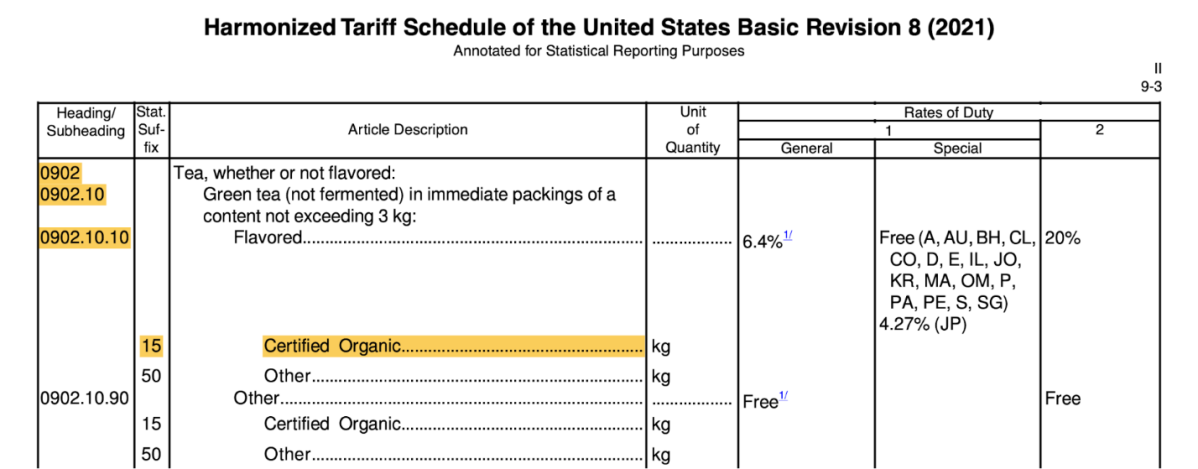

The first and most basic problem with the proposed system is simply administering it. Tariffs in the United States (and elsewhere) are applied on a product-specific basis per a “tariff schedule” that assigns each product an identifying number up to 10 digits (the most granular level) and a corresponding tariff rate, depending on its origin. The Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) lists more 5,000 items at the somewhat-detailed six-digit level and has three different tariff rates for each item: general (the standard “most favored nation” rate for World Trade Organization members); special (lower, “preferential” rates for trade agreement partners and a few others); and Column 2 (high/discriminatory rates for non-WTO members like Iran). Here’s a random example:

By applying a different tariff rate for each country (based its own tariff equivalent on the same product from the U.S.), Trump’s reciprocal system would replace the three columns on the right side of the image above with more than 150 of them. (There are 186 nations in the World Customs Organization.) That potentially translates to 150-plus tariff rates for thousands of different products listed in the HTSUS, or about 750,000 tariffs (six-digit level) in all. Do it for all 17,000 lines (10-digit) in the schedule and all 183 WCO countries, and you’re talking more than 3.1 million different tariffs, plus any special duty rates (punitive or preferential) for various U.S. trade programs, including ones Trump himself is implementing on Chinese and other imports.

As recently laid out by Jennifer Hillman and Edward Alden at the Council on Foreign Relations, this complexity raises two immediate problems. The first is simply the public and private resources—time, money, manpower—to maintain the new system:

Customs and Border Protection would require different tariff schedules for each country—close to impossible for a short-staffed agency. Already, the Trump administration was forced to delay the immediate elimination of the de minimis exception for goods from China, which allows shipments of less than $800 to enter tariff-free under a truncated process, because Customs could not handle the volume of work associated with reviewing import documents and assessing duties on so many shipments.

As one trade lawyer recently told the New York Times, simply creating and monitoring these new tariff lists would be “a herculean task” requiring countless hours and numerous new government employees tracking thousands of different tariffs. And their task would only get more difficult after the system is implemented, countries change their tariff and nontariff policies, or, as discussed next, supply chains shift in response to the new reciprocal tariff regime.

Private parties would need to stay caught up too. Cindy Allen, CEO of Trade Force Multiplier and bona fide customs compliance guru, sums it all up in an email:

Updating tariff numbers by the government would be a weekslong process instead of the few days it takes now. And then the private sector would need to download the duty rate updates individually as well. This would be a massive endeavor for both the government and the private sector to keep track of on an ongoing basis and extremely challenging for any post entry activities trying to figure out which rate applies.

In short, simply maintaining the new tariff system would be a bureaucratic nightmare for everyone involved (someone alert DOGE!).

Second, Hillman and Alden add, there’s the increased paperwork and costs associated with tariff compliance and enforcement:

[M]ost companies and the Customs brokers that facilitate exports and imports do not pay much attention to the fine print of exactly where products are made, the so-called rules of origin. Rules of origin matter greatly for imports from free trade partners, for products covered by country-specific antidumping or countervailing duties, for goods coming from non-favored countries (such as Belarus, Cuba, North Korea, and Russia), and for preventing the import of products made with child or forced labor. But for all other shipments, there is no need to ensure rules of origin declarations are 100 percent correct, because it does not matter. Under the [current Most Favored Nation] rules, the tariffs are the same no matter where the goods were made.

As I can tell you from experience, a single customs ruling on a product’s country of origin or its applicable tariff rate can take months of work and loads of evidence. Fortunately, they’re relatively rare under the current system: Even with all the recent tariff threats, CBP issued just 106 rulings in the last 30 days. Under a reciprocal system, however, these and other customs rules and procedures would matter not for a few products and countries but for every single thing entering the United States—trillions of dollars’ worth of goods each year—no matter their origin or their complexity. Related costs would accordingly skyrocket.

Finally, there’s the similarly herculean task of defining and quantifying all the nontariff barriers supposedly blocking U.S. exports and then converting them all into a single “tariff equivalent” for an entire country. As Trump may or may not be aware, trade-distortive foreign subsidies (e.g., government grants to domestic exporters) can already be investigated and subjected to remedial measures under both the U.S. “countervailing duty” (CVD) law and WTO rules, but these cases take more than a year—along with piles of documents, armies of lawyers, and multiple government-to-government consultations—to carry out for just a single product. In the CVD context, moreover, it’s often discovered that foreign exporters under investigation didn’t receive some of the subsidies being alleged, entitling their goods to lower U.S. duty rates (or none at all). Other times, alleged subsidies didn’t even exist, and—even when they do—they’re often product specific, not country-wide (e.g., subsidized logs going to foreign lumber producers). In these common cases, slapping a single “subsidy tariff” on an entire economy would be absurd.

Then there are domestic government policies with highly uncertain and indirect trade effects. Economists will tell you, for example, that value-added taxes are—contra the Trump team—trade neutral in theory, but whether a nation’s VAT system affects imports and exports in practice can depend on the tax’s structure and whether, for example, local currency adjusts fully and quickly. Labor, environmental, intellectual property, and other domestic policies also can have indirect trade effects, even though they’re non-discriminatory on their face. Heck, even the metric system can be a nontariff barrier. Mimicking the CVD process for 150-plus countries, thousands of products, and thousands of government programs—not just tariffs and subsidies!—is simply impossible. So, either the Trump team will fake it, or they’ll give up.

Let’s hope it’s the latter.

A Gaming (and Lobbying) Fiesta

The system’s complexity leads to its second big problem: Given the money at stake, companies and countries will inevitably work to circumvent new U.S. tariffs, adding even more pressure on customs enforcement along the way. Companies might, for example, reroute supply chains through countries that suddenly face lower U.S. tariffs on certain products (because those countries had lower tariffs on the same products from the United States). Or they’ll engage in “tariff engineering” to slightly change a product from one with a high tariff to one with a lower one. Or they’ll find other legal loopholes—and illegal ones, too—to continue shipping goods to the United States. And, of course, they’ll hire lobbyists to convince administration officials that they deserve special tariff treatment one way or another.

As the Financial Times’ Alan Beattie notes, a system with widely varying tariff rates across dozens of countries (and with corporate armies looking to game it) would cause U.S. trade policy and enforcement to quickly devolve into a “truly global game of whack-a-mole” that the United States can’t easily avoid:

If the US genuinely tries to close its overall deficit with big tariffs all round, it will cause a crunching recession. If Trump discriminates between trading partners, the heavily tariffed ones can nip through the side door of those who escaped more lightly.

We’ve recently seen this exact outcome play out repeatedly on a smaller scale. As we discussed last year, for example, U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports have been less effective than advertised because companies have found creative (mostly legal) ways around them. Logistics professionals proved similarly nimble when the pandemic and other disasters hit, quickly rerouting goods and supply chains to keep trade flowing. And trade lobbying has skyrocketed in our new era of tariffs and policy uncertainty.

Overall, tariff evasion is as old as the republic itself, and—as we’ve learned quite well with our domestic tax system—smart lawyers, accountants, lobbyists, and other professionals make a killing (for themselves and their clients) exploiting regulatory complexity. A reciprocal tariff system would be complexity on steroids.

As Beattie acknowledges, supply chain adjustments in response to reciprocal tariffs wouldn’t be painless, and—as with China—the result would likely be less efficient, less resilient, more costly, and less transparent than our current system. But in the end, it’s a safe bet that, as Beattie puts it, “the world’s supply chain superheroes” (and their friends on K Street) will eventually outfox Peter Navarro.

Assuming, of course, that—as with the administration’s failed attempt to block de minimis shipments from China—the whole Rube Goldbergian thing doesn’t collapse first.

What About U.S. Trade Barriers?

The system’s third big problem is its treatment of U.S. trade barriers. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, the United States has relatively low average tariffs but plenty of high ones on politically sensitive products like sugar, dairy products, textiles and apparel, footwear, and pickup trucks. Just as importantly—

Washington uses many “non-tariff” measures to impede foreign competition. This includes subsidies, quotas, “Buy American” restrictions, the Jones Act (drink!), and regulatory protectionism like the FDA’s blockade on baby formula. We’re also one of the biggest users of “trade remedy” measures (anti-dumping, especially) and today apply more than 700 special duties on mainly manufactured goods like steel and chemicals.

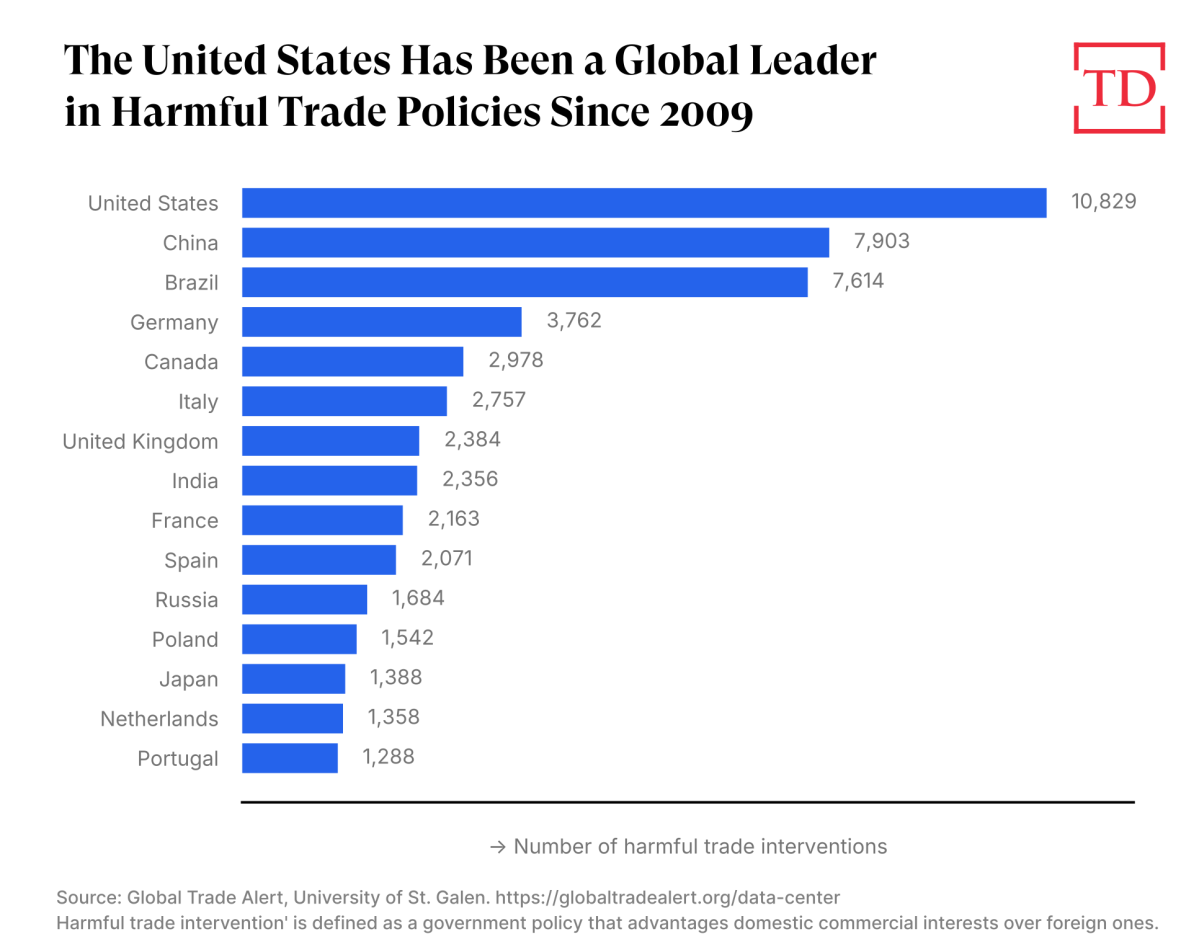

According to the independent Global Trade Alert, which monitors nations’ trade liberalization and protectionist policies, the United States has had the most “harmful” trade interventions—tariffs, nontariff barriers, subsidies, etc.—of any nation since late 2008.

Nitpick the organization’s methodology all you want, but the fact remains that the United States has plenty of its own barriers to trade—most of which are hardwired into domestic law and usually backed by powerful domestic constituencies (Big Sugar, Big Steel, Big Auto, Big Dairy, Big Ship, Big Peanut, etc.) and large congressional majorities. Some major exporting nations, by contrast, have low tariffs on these very same products. For example, Japan’s tariff on U.S. pickup trucks is 0 percent, while our tariff on Japanese trucks is 25 percent; Brazil’s tariff on raw cane sugar is 14.4 percent, but ours is around 81 percent at current market rates; New Zealand has no tariffs on milk, butter, and cheese, while U.S. tariffs are in the double digits.

A truly reciprocal system would lower U.S. tariffs to match the tariffs of these and other trading partners, but, given the politics here, there’s effectively zero chance of that ever happening. Instead, the most likely outcome is that U.S. tariffs move only one way—up—and foreign countries respond to our trade barriers with new ones of their own.

So Much for Comparative Advantage

Fourth, the reciprocal system ignores nations’ natural comparative advantages in ways that would produce absurd results. For starters, the United States would end up applying high tariffs to things that we don’t make for reasons that have nothing to do with trade policy. Take coffee, for example. Because of climate and geography, the United States produces relatively little coffee, imports a ton, and—to the delight of caffeine addicts everywhere—applies no tariff on imports of green coffee beans. Brazil, on the other hand, is the world’s largest coffee exporter and applies a 9 percent tariff on imports. Under a reciprocal tariff regime, the United States would mindlessly match Brazil’s tariff, thereby accomplishing nothing for U.S. exports while harming millions of American coffee roasters and consumers. Plenty of other food and beverage products, along with specialty or name-brand manufactured goods, are made only by specific countries and companies and would thus suffer the same fate. How silly is that?

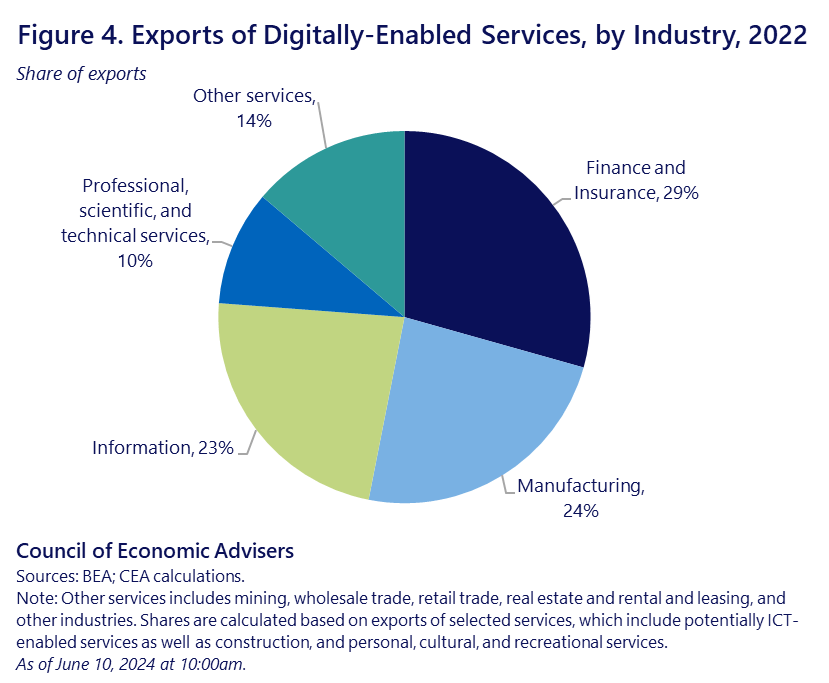

Just as importantly, the Trump/Navarro reciprocal system ignores all the services industries in which the United States is a global leader and export powerhouse. (We have a big trade surplus in services, if you’re into that sort of thing.) Major U.S. exporting industries include information technology, financial services, professional services (accounting, law, etc.), entertainment, tourism, and as the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers explained last year, manufacturing:

Economic activity in the United States has transitioned from manufacturing towards services over the past five decades. Notably, U.S. manufacturing firms account for almost a third of this transition—reflecting the importance of services throughout the manufacturing process. In fact, manufacturers are an important source of the U.S. comparative advantage in digitally-enabled services. Manufacturers are the second largest exporter of digitally-enabled services after the finance and insurance sector (figure 4).

A “reciprocal” system that focuses myopically on tariffs and trade in goods will miss all this important economic activity and the real barriers to U.S. services exports in key foreign markets—barriers that the United States government has long documented and that harm some of the nation’s biggest and most important companies, including American manufacturers. In short, we’d obsess over nations’ banana tariffs while ignoring their barriers to American AI. That’s just crazy.

So Much for ‘America First’

Dartmouth economist Doug Irwin explains the final problem with simplistically applying the same tariffs on other countries’ imports as they impose on U.S. goods:

It amounts to outsourcing U.S. tariff policy to other countries. They would dictate what our tariffs would be. If other countries put high tariffs on American goods, then we would impose high tariffs on their goods. So much for American sovereignty. So much for deciding what’s in our own national interest. The British economist Joan Robinson once said that a country shouldn’t throw rocks into its own harbors just because other countries have rocky coasts. The same principle applies here: The U.S. shouldn’t have stupid tariff policies just because other countries have stupid tariff policies.

In general, the United States should remain free to improve its economy without the need to wait for other countries to do likewise. Regardless of whether you think the United States needs higher or lower tariffs, the decision should be based on what’s best for most Americans and the nation as a whole, not what some random government official in some random country decides on a random day (often for political, not economic, reasons). A reciprocal approach to policymaking is particularly wrongheaded today, given the United States’ continued economic outperformance versus its global peers. And it’s especially weird coming from “America First” proponents who decry—sometimes rightly—“globalist” policies that cede U.S. policymaking and sovereignty to foreign powers and international organizations. Indeed, Trump literally just withdrew the United States from an international arrangement that would’ve tied the United States’ hands on corporate tax policy, but now he wants to tie our own hands on VATs and tariffs?

Make it make sense.

Summing It All Up

As noted at the outset, these are not the only problems with the Trump/Navarro reciprocal trade plan. It defies, for example, the WTO’s bedrock nondiscrimination principle and could therefore implode a multilateral trading system that’s been around since the 1940s. It leads to higher U.S. tariffs, raising costs and stifling growth (see new analysis here). It misunderstands that—thanks to global supply chains, multinational investment, and intrafirm transactions—bilateral trade flows are rarely a simple case of “their” exports versus “ours.” It ignores all the U.S. laws already in place to handle “unfair” trade policies—laws Trump himself has used—and the many other tools at the United States’ disposal to address other countries’ protectionism without harming its own citizens. It whiffs on the real causes and effects of U.S. trade deficits (spoiler: it’s not tariffs), as well as the utter meaninglessness of bilateral trade balances for assessing national trade policies. It misses fundamental differences between tariff-centric developing country trade policy and nontariff-centric developed country policy—differences driven mainly by resources (money, manpower, etc.), not economics or “fairness.” And it fails to grasp how traditional trade agreements—and the standard version of reciprocity that seeks an overall balance of concessions among parties, with different carveouts for nations’ specific political sensitivities—have historically done a pretty good job reducing tariff and nontariff barriers and adjudicating specific bilateral trade irritants, while leaving nations adequate domestic policy space to tax and regulate as they see fit.

These are all good and valuable critiques, and I’m sure there are others. But, perhaps even more important than all the wonky law and economics is the simple fact that a reciprocal tariff system would be an unworkable, impractical, nonsensical mess. It’s the type of thing you’d expect from a dorm-room bong session, not an official policy document issued by the head of the world’s most powerful nation. For now, the president has merely directed various agencies to study the feasibility of these reciprocal tariffs and determine the way forward. For all our sakes, let’s hope there is none.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.