Dear Capitolisters,

A few months ago, a tweet thread about institutional investors increasingly buying single family homes (and thus turning America into a “nation of renters”) caught the attention of several populist media darlings and political aspirants, and became a major talking point for a few days thereafter. As with most shiny objects, the issue was eventually abandoned by the populists (who of course just moved on to the next thing to yell about), but numerous stories from more reputable outlets have since arisen to lament the plight of American homebuyers who are suddenly forced to compete with a new and cash-rich challenger for scarce housing resources: investors. (Insert scary music here.) Some folks have even proposed raising taxes on second homes or rental properties to make housing investment less attractive and to level the playing field for individual homebuyers, especially first-time buyers with limited cash and paperwork-heavy (subsidized by the Federal Housing Administration) mortgages.

It thus seems like a perfect time to check in on the housing market again and ask whether the Rise of the Home Investor really is a serious problem requiring serious policy punishment. (Spoiler: It sure doesn’t look like it, at least not yet.)

The State of the Housing Market

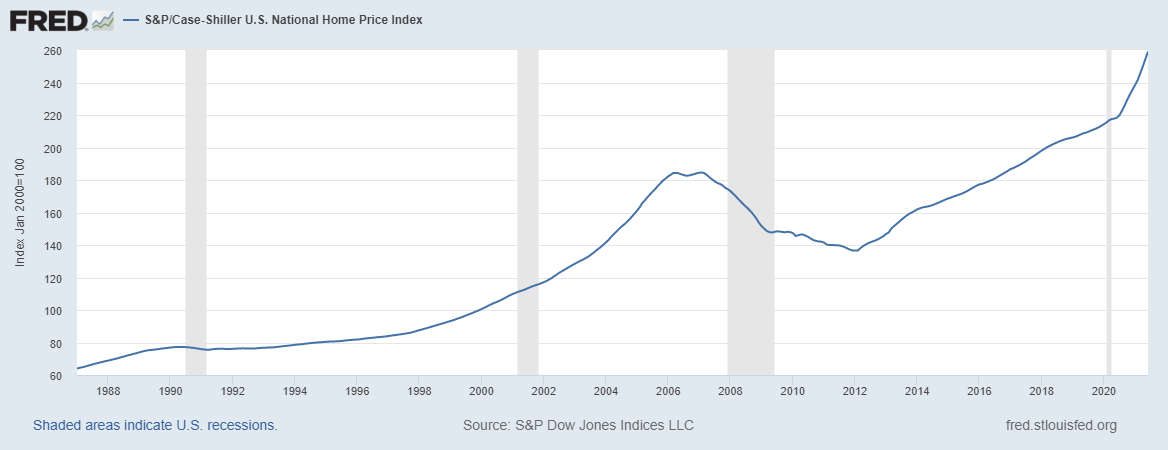

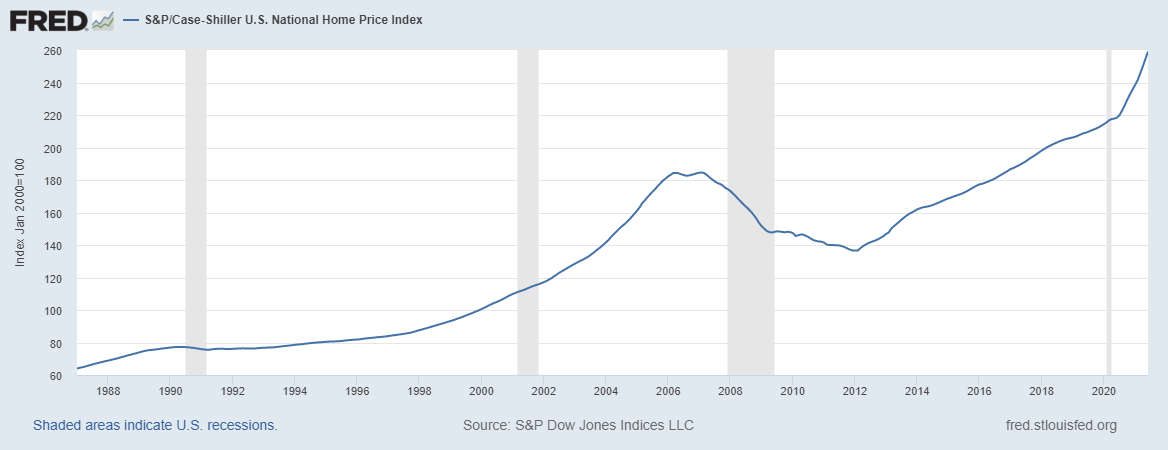

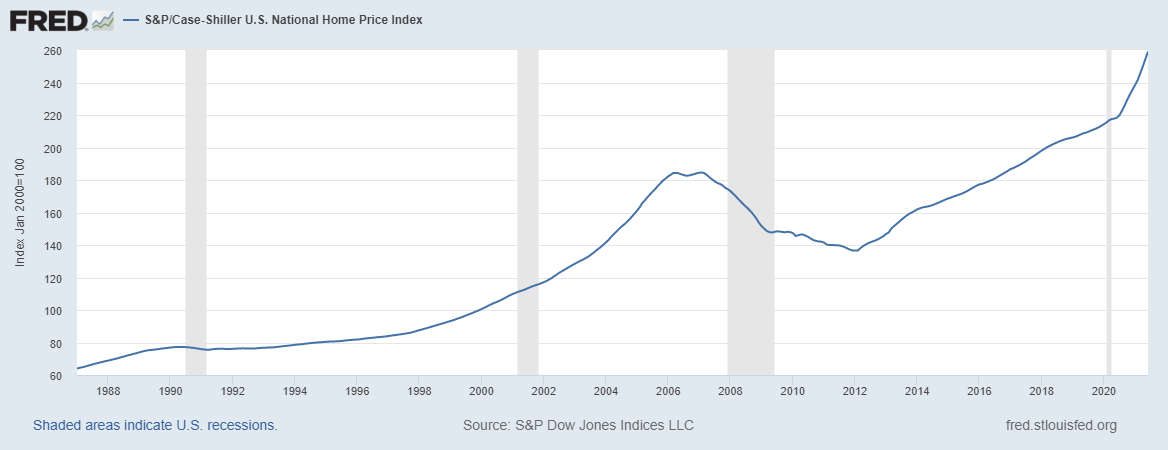

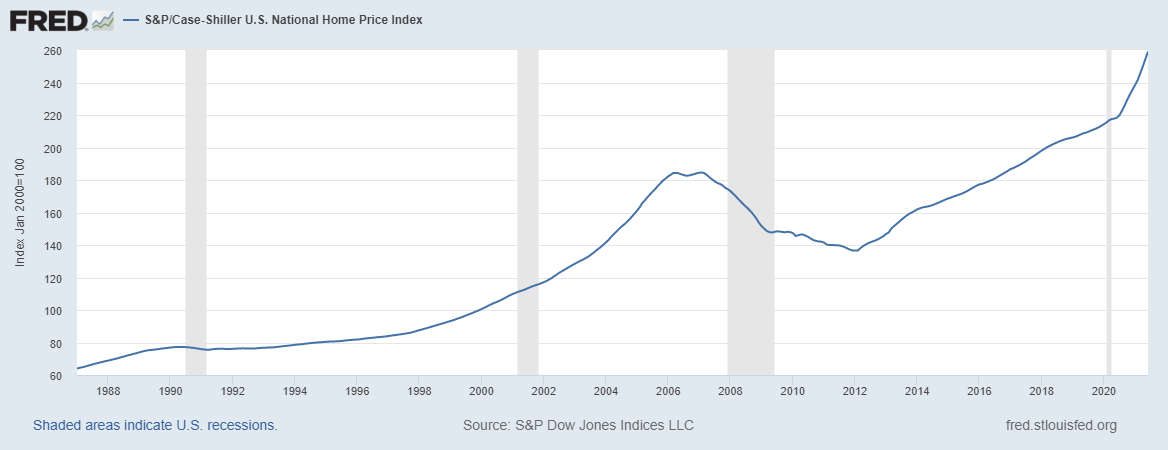

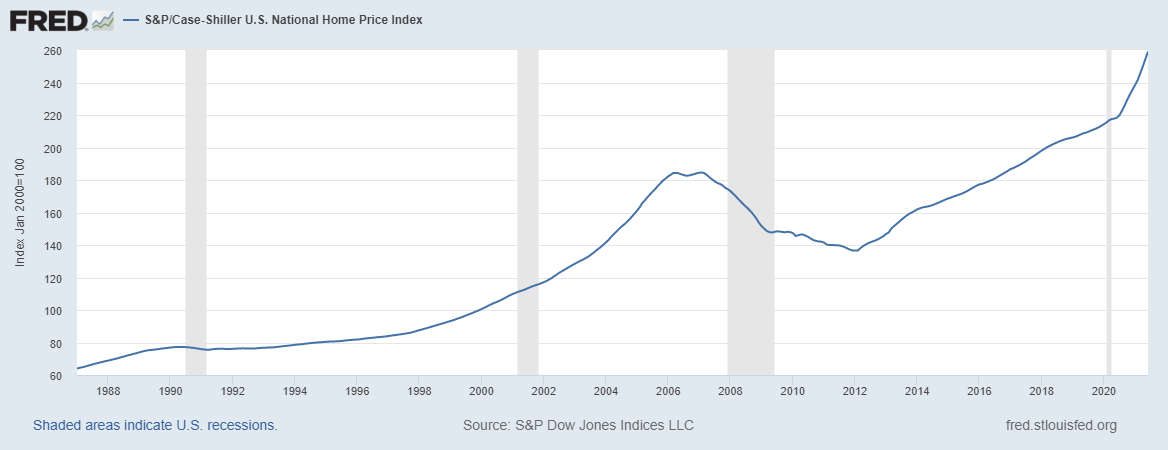

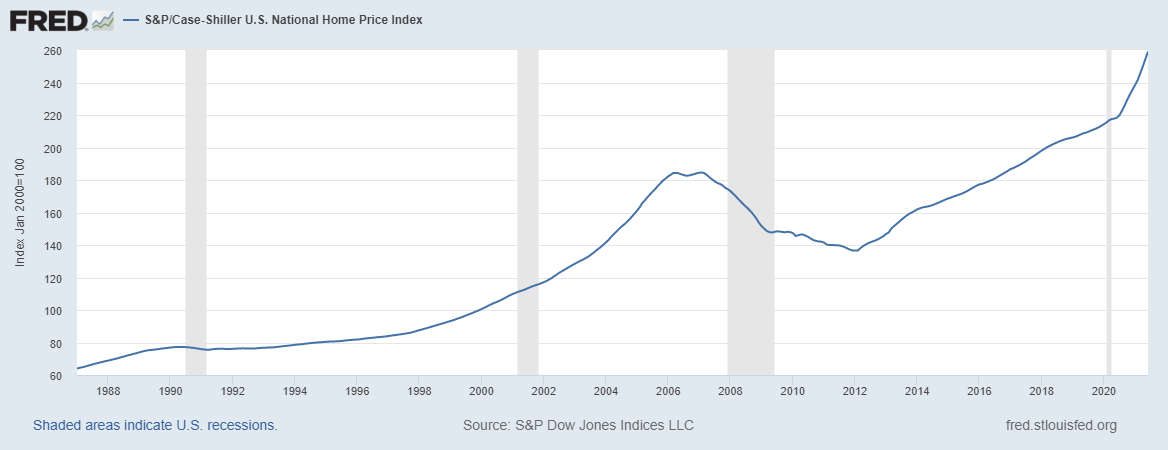

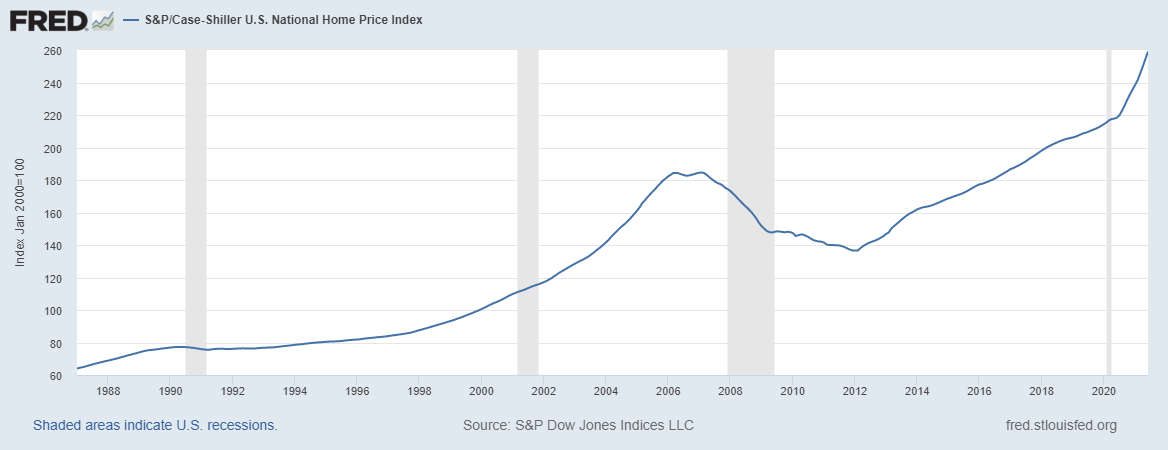

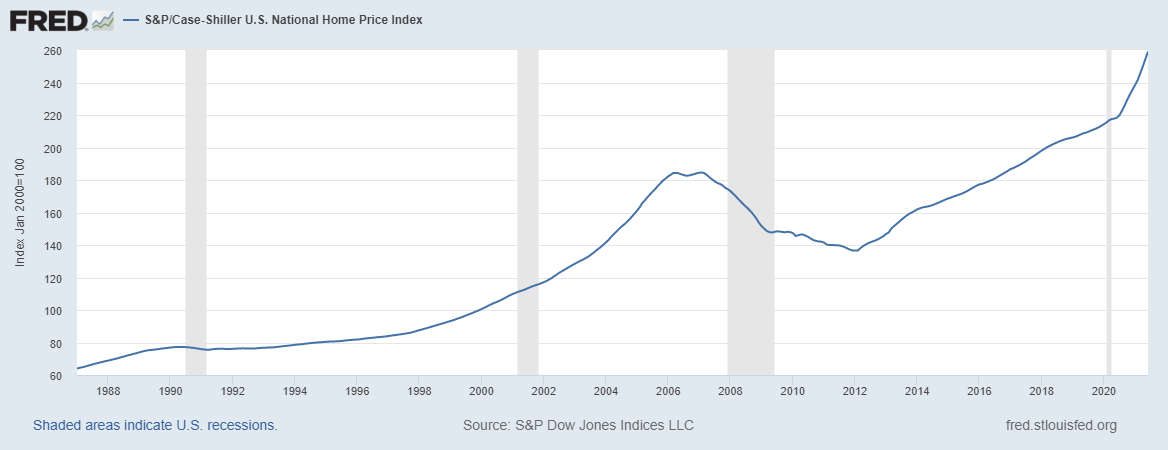

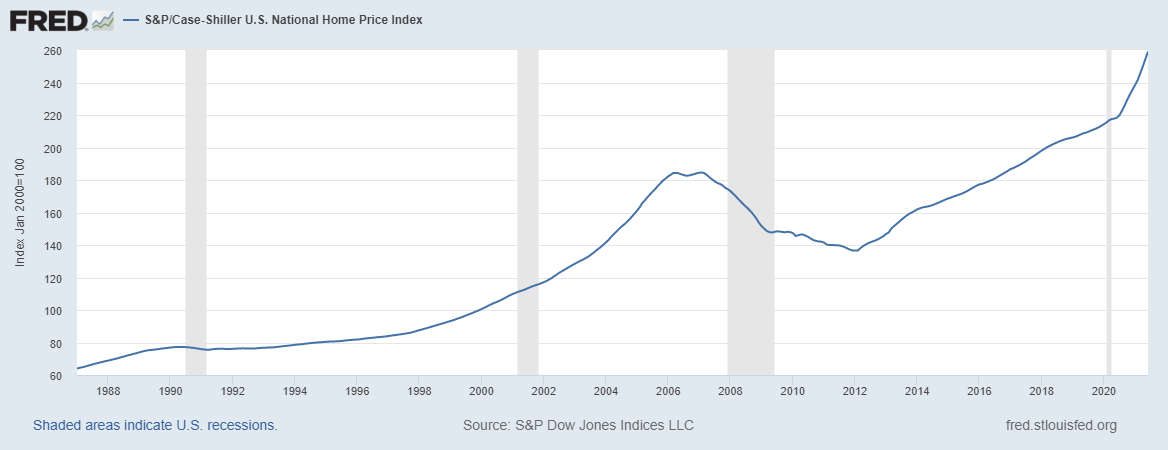

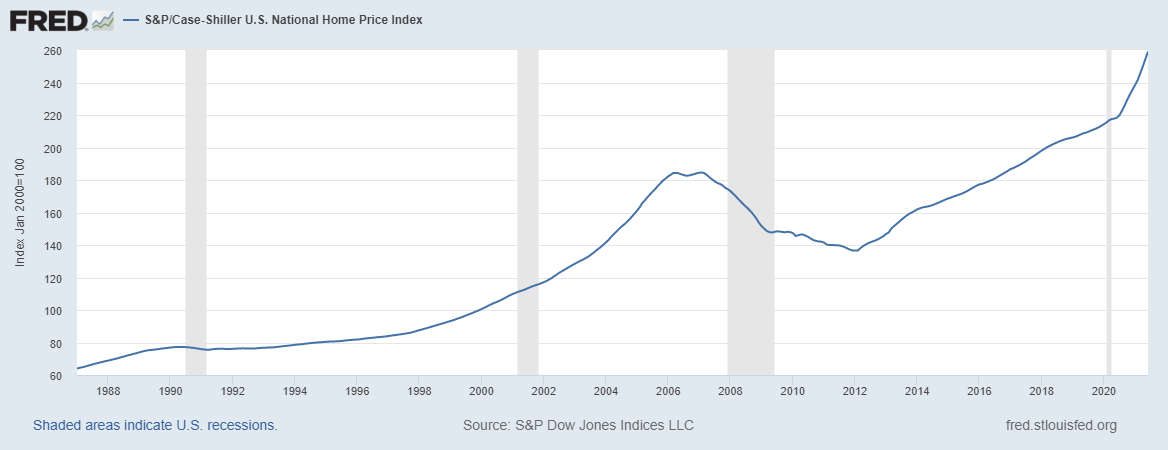

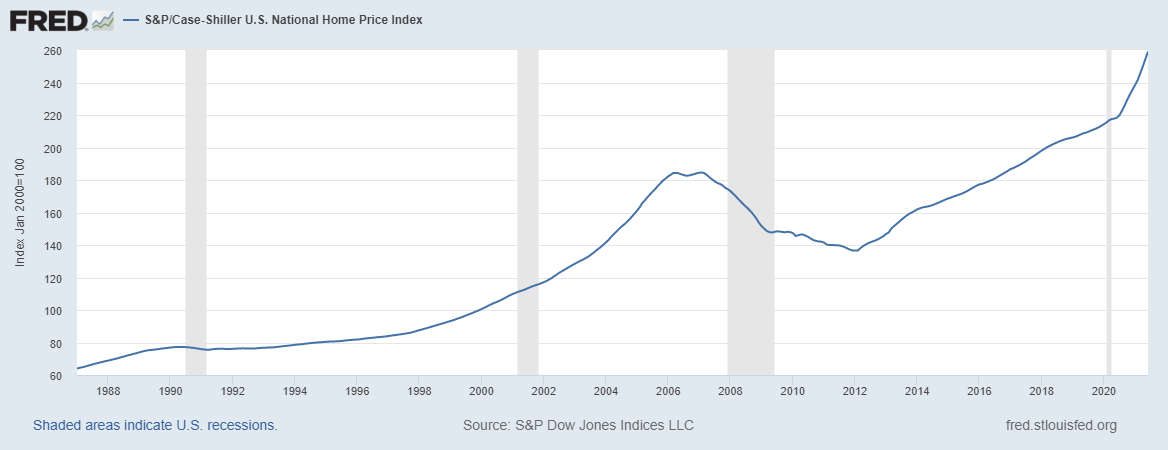

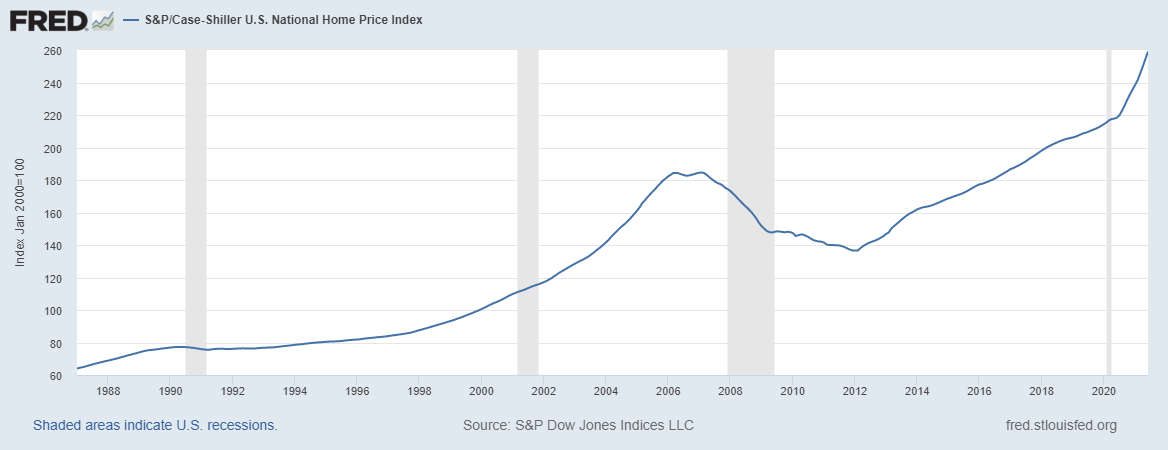

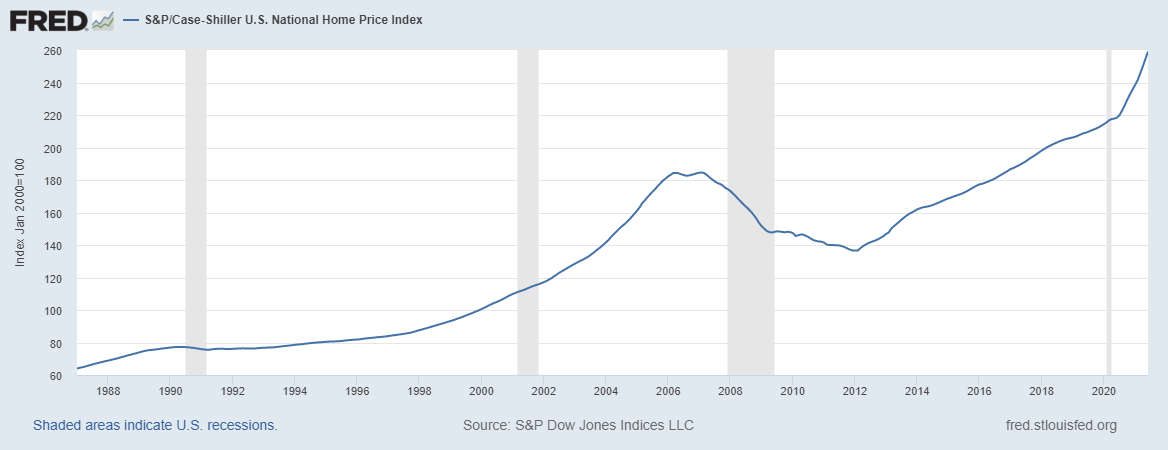

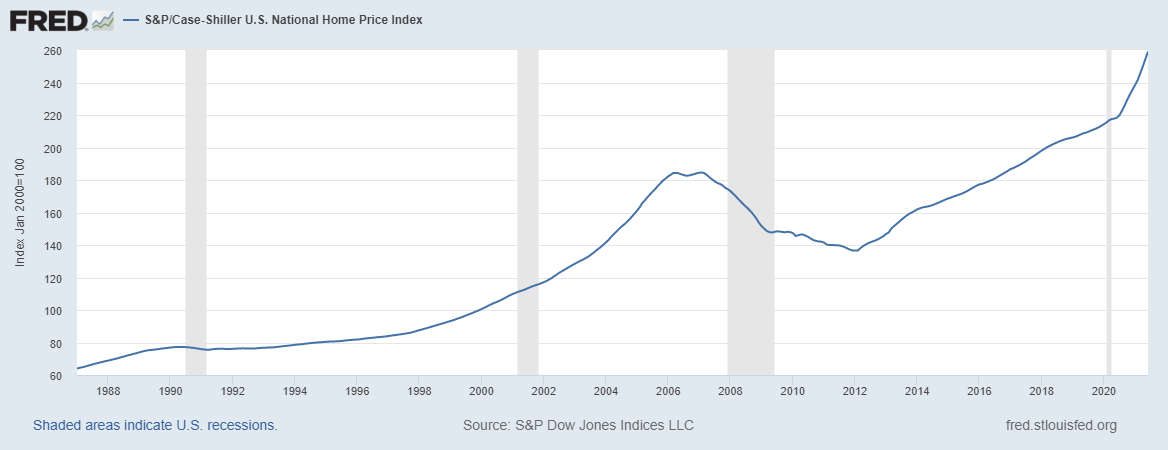

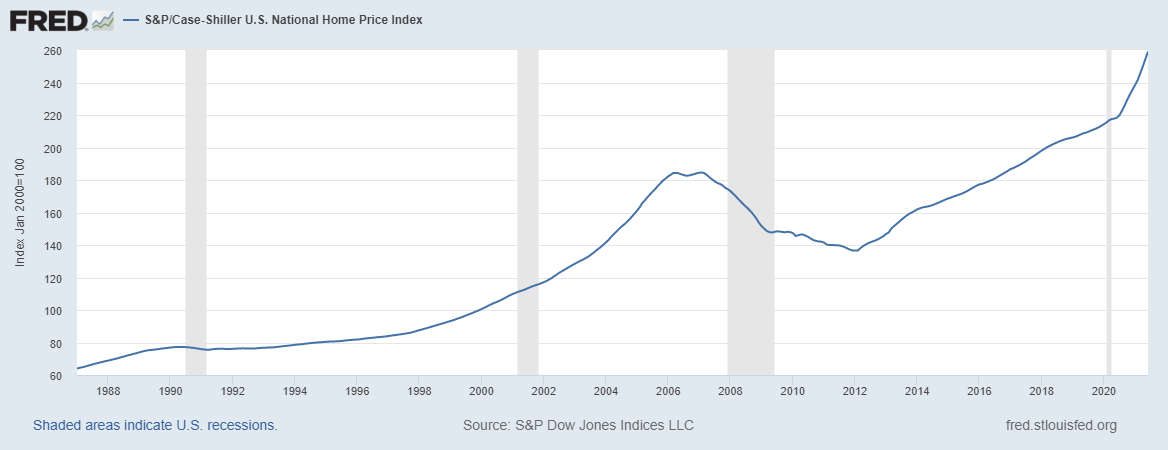

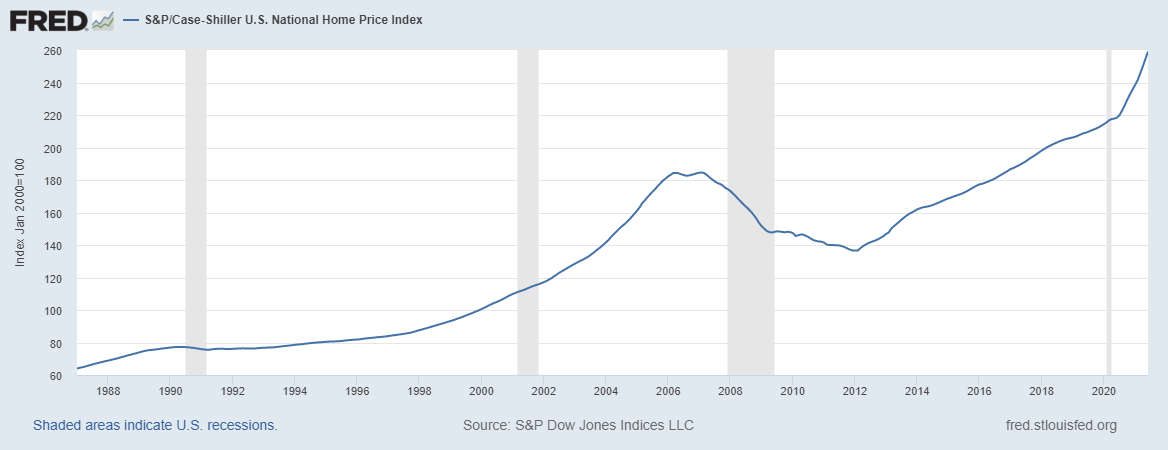

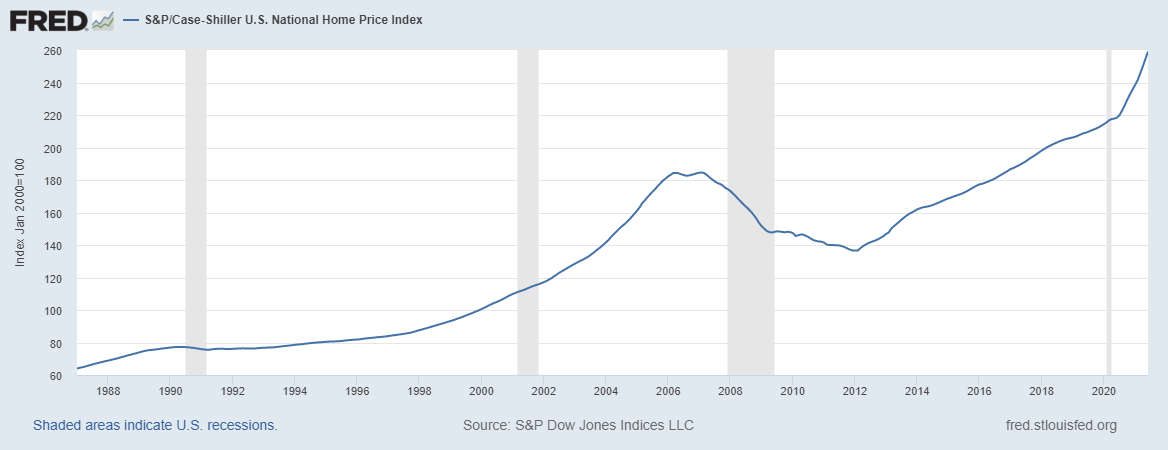

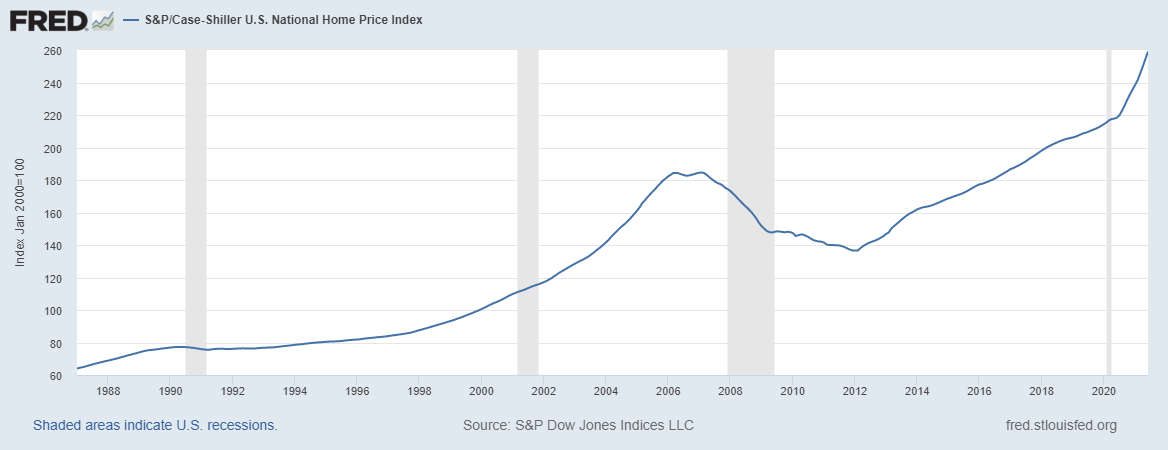

There’s little doubt that home prices are surging in the United States, with various national home price trackers hitting all-time highs this summer (for any charts that are difficult to read, please click on them to zoom in):

Over at the new site Full Stack Economics, economist Alan Cole recently highlighted one region—the Mountain West—that’s especially frothy right now:

At the same time, it’s also true that many investors—institutional (big banks, hedge funds, etc.) and wealthier individuals—are turning to residential real estate, especially single family housing, as an alternative investment vehicle because they’re flush with cash and see few opportunities for good returns in the current low interest rate, low-yield environment. As financial adviser Adam Strauss laid out in Forbes back in January, investors’ portfolios are traditionally heavy in stocks and bonds, but the latter has become “almost uninvestable” right now: “Investors in U.S. Treasuries, investment-grade municipal bonds, and investment-grade corporate bonds are likely to generate negative real (inflation-adjusted) returns for years.” Thus, all that capital is looking elsewhere for the time being, and residential real estate—either as a landlord or through a private fund—is one of several alternatives investors are pursuing.

And, on its face, investors’ recent shift into residential real estate appears significant. For example, an April 2021 report from John Burns Real Estate consulting finds several hot housing markets in which investor sales are surging:

A report from the Wall Street Journal around the same time—the one that appears to have fueled the initial populist backlash—quoted that research and numerous anecdotes of institutional investors outbidding individuals, often by significant margins, in hot housing markets around the country. Other reports have added similar stories, often throwing around big-sounding numbers too:

-

“Funds managed by Invesco Real Estate are backing Mynd Management to spend as much as $5 billion, including debt, purchasing about 20,000 single-family rental homes in the U.S. in the next three years”;

-

“Investors snatched up $77 billion worth of homes— a record—making it even harder for regular buyers to buy one”);

-

“Investors purchased $87 billion in homes in the first half of 2021 … including a record 68,000 houses in the second quarter … Tricon launched a $5 billion fund this summer … to acquire 18,000 more houses and convert them into rentals.”

There are also numerous reports of out-of-state cash buyers outbidding locals with FHA loans, and new data indicate that cash purchases have indeed increased in recent months (“Across the country, cash purchases accounted for 34% of all single-family home and condo sales in the second quarter of 2021)—a factor that some attribute to “big investors” snapping up houses, bidding up prices, and more generally “dominating” today’s housing market.

However, plenty of other data show that investors really aren’t eating the U.S. housing market like many folks currently fear. Most notably (and echoing my innumeracy column a couple weeks ago): These scary stories routinely lack the necessary data to come to broader conclusions about investors’ effect on the U.S. housing market and American homeownership. For example, they’ll omit the overall size of the local and national markets at issue (i.e., the denominator that one would need to determine whether investors are a major force there) and investors’ historical presence in those same markets (i.e., the baseline figure upon which percentage increases are determined). Jerusalem Demas helpfully provided some of these data in a June piece for Vox, in which she showed that institutional investors have historically been a tiny share of the U.S. housing market:

[I]nstitutional operators owned just 300,000 single-family units in 2019. For context, the researchers point out that there are roughly 15 million one-unit detached single-family rental homes. (There are roughly 80 million detached single-family homes total in the US.)

Data from the Census Bureau show, moreover, that there were almost 5 million single-family homes sold in the United States in the first half of the year, and the country has averaged between 1.5 million and 2 million sales per quarter for the last several years:

Because institutional investors are starting from a very low base and because there are so many houses (existing and sold) in the United States, a large percentage or nominal increase in investor acquisitions might sound really big (especially to us innumerate Americans), but that change will actually represent a small fraction of total U.S. houses or sales. For example, those 68,000 investor-purchased houses mentioned above represented only 3 percent of the 2.2 million single family home sales that occurred during that record-setting period. (Even limiting the denominator to the 50 biggest markets, these investor sales represented only 16 percent of the second quarter total – larger, sure, but still not “dominant.”) Over a slightly longer period, the trends are even more moderate, as the Journal recently noted: “[I]nstitutional investors … bought just one in 500 U.S. homes sold in the 12 months after the Covid-19 crisis began…. Currently, just 2% of all the single-family properties available for rent in the U.S. are in the hands of institutional investors.” The market thus remains one “dominated” by individual buyers.

Demas goes on to cite research showing that total investor (i.e., not just institutions) purchases of U.S. homes actually declined last year, and that—as of April 2021—rental homes remain a small share of single-family homes and an even smaller share of total U.S. housing, even in hot markets:

Finally, historical data from Redfin reveal that the “new” trend of investors buying single family homes isn’t actually new at all and is up only a smidge from 2013 levels, with the biggest long-term change coming in multifamily housing like apartment buildings:

Ironically enough, even the Journal article that first revved up the Populist Rage Machine showed that the growth rate for single family rental homes actually began long before the pandemic:

Thus, investors’ turn to housing for good financial returns is part of a long-term trend dating back almost a decade, and they’re still a relatively small share of the market.

Finally, the latest housing data from the Census Bureau continue to show little reason to think that America’s turning into a “nation of renters” (or whatever)—regardless of whether the landlords are big banks or wealthy boomers. For example, the U.S. homeownership rate (i.e., the number of occupied housing units owned by the occupant) was 65.4 percent in the second quarter of 2021—slightly higher than it was before the pandemic began and rising since 2016 in tandem with the share of investor-owned properties:

Other national census data further show that there hasn’t been a surge of renter-occupied units, units for rent, seasonal/vacation homes, or occasionally used properties since before the pandemic:

Local data tell a similar story, even in many of the hot investor markets noted in that John Burns report above. As shown in the following chart, for example, there’s no clear trend in declining home ownership rates in the places reportedly overwhelmed by investors (who would not be a unit’s primary occupant). Instead, rates are generally fluctuating within the same band and even up in many of these hot markets since before the pandemic began.

This isn’t to say, of course, that investors aren’t affecting any markets anywhere. Surely, there are lots of them in the market today, and they’re often outbidding some normie homebuyers in the process. But if these folks are working to turn America into a nation of renters, they’re doing a pretty lousy job.

So What’s Really Going On? (And How Can We Really Fix It?)

So if evil Blackrock and rich boomers aren’t driving the current pricing boom, then what is? As Cole mentions in his piece, it’s mostly just supply and demand doing its thing. On the demand side—

The biggest force propelling real estate prices upwards is a rising number of relatively high-earning households ready to buy, and a large pool of savers ready to lend to them at favorable rates.

Every year, the U.S. mints about two million new households with six-figure incomes. For example, if you go by tax data, there were 27.7 million households with more than $100,000 in taxable income in 2017, and 29.7 million such households in 2018.

These high-income families can afford to spend a great deal on housing. At today’s low interest rates (often about 3 percent), even a household with an income of just $100,000 can easily be approved for, and afford, a $500,000 loan.

Furthermore, many households are willing to pay a premium to get the best house they can afford. So each year there are as many as 2 million new households able and willing to purchase real estate at prices well above the national average.

Meanwhile, Cole adds, this flood of demand has hit a wall of supply, thus causing prices to rise: “The US only starts about 1.2 million new houses each year. So even if every single new home went to a family with a six-figure income, there would still be hundreds of thousands of other affluent families out there bidding up the price of older homes.” A couple more charts show the current supply crunch and how builders are nowhere near the output of the mid-2000s:

Build too few houses year after year, and you dig quite the hole: the National Association of Realtors estimates that the U.S. was short around 5.5 million units (2 million single-family homes) as of June 2021, because construction of new homes between 2010 and 2020 was well “short of what was needed to meet household-formation growth and replace units that were aging or destroyed by natural disasters.”

According to Demas and numerous other reports, this longstanding and fundamental supply-demand imbalance is what’s driving prices higher and thus attracting yield-starved investors to the U.S. housing market. Two new things, however, have likely added fuel to the fires:

-

First, as Cole notes, three facets of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—the cap on mortgage interest deductions, the cap on state and local tax deductibility, and the doubling of the standard deduction for married couples—“made homes in expensive markets less valuable” and gave people a financial incentive to move to “[r]egions that relied less heavily on these deductions.” This includes a lot of places that are today experiencing housing booms, like Arizona, Georgia, Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and North Carolina. And it partially explains all those cash offers: people who sold their expensive houses in hot markets often buy their next house in cash (especially when it’s cheaper).

-

Second, there’s the pandemic (isn’t there always?!?), which motivated some newly-remote workers to move, riled construction labor markets and materials supply chains, and—as shown in the chart above—caused homebuilders to stall projects or keep inventory off the market while demand recovered.

As noted in a recent Goldman Sachs report, these additional factors should abate in the coming months. However, demand from millennials and movers will undoubtedly continue, and the weak supply side will too—unless there’s real policy reform (emphasis mine): “While the easing of temporary bottlenecks, such as material constraints and pandemic labor supply effects, should support an eventual recovery in supply … more persistent constraints, such as land use regulations, should continue to push up house prices in coming quarters, especially in the US, Canada, and UK.” Indeed, as we discussed in December, these “persistent constraints”—especially land use regulations—make homebuilding in many American localities prohibitively costly and time-consuming, and are likely the biggest thing holding back new U.S. housing supply. (For those interested in more on this issue, I recommend this cool new cartoon.) As Harvard economists Edward Glaeser and David Cutler explain in a new Journal essay, moreover, housing restrictions are likely slowing U.S. economic dynamism too.

Given these realities, the way to fix the nation’s current housing problems isn’t by taxing hedge funds or whatever (taxing investment properties probably doesn’t work anyway), it’s by deregulating local housing markets and making it quicker and easier for builders to build—especially in popular markets. Glaeser and Cutler offer a few concrete examples of what these policy reforms might look like:

How can America once again become a nation for outsiders? With housing, the key actors are state legislatures, because they can rewrite the rules of local zoning on a dime. Last month, the California legislature passed a law that could make the permitting of two-unit projects far more automatic. It’s a good beginning, but states should go further and only allow localities to impose regulations and rules that have gone through rigorous cost-benefit analysis. They can institute one-stop permitting that allows new businesses to deal with a single authority instead of many overlapping government offices. The federal government can help, too: There is no reason why infrastructure dollars can’t be directed to communities that permit the most new construction.

“And housing advocates routinely offer plenty of other market-based fixes—fixes that, if adopted, would not only make housing more affordable for you and me, but also make it less attractive to Wall Street in the process. But these reforms are messy, piecemeal, and complicated—undoubtedly met with resistance from entrenched local and national interests and slow to correct the housing market’s long-term imbalances.

Much easier to just rage against Blackrock on Twitter.

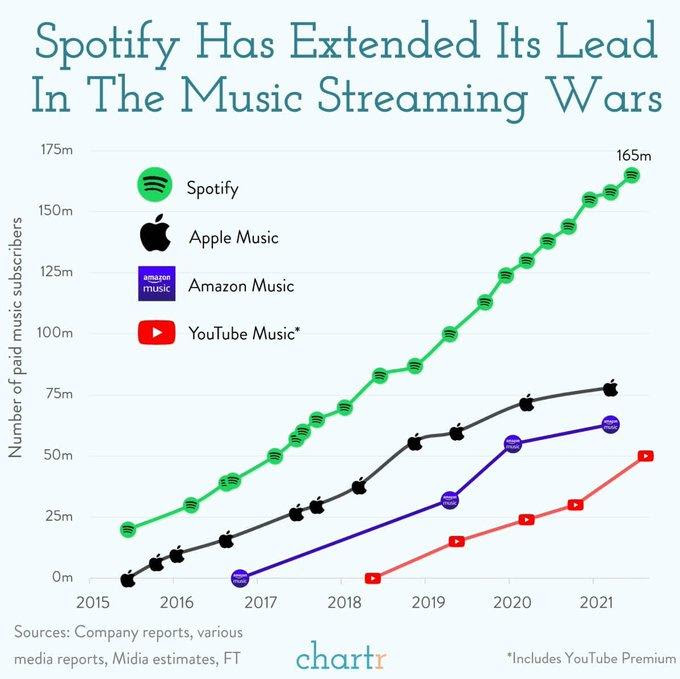

Chart(s) of the Week

“Are Millennials much poorer than prior generations were at the same age?” (Spoiler: no.) More data in this thread.

Bonus Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.