Dear Capitolisters,

Recent events have me thinking (as one does) about prices—or, more accurately, how seemingly no one in politics knows what they are. Just last week, for example, Jones Act lobbyists who opposed a waiver for that BP diesel tanker we discussed simultaneously claimed that there was no fuel supply problem in Puerto Rico, and that BP was charging “premium” prices there because of Hurricane Fiona. The same day, Florida officials took to the airwaves to warn against “price gouging” before Hurricane Ian made landfall, and President Biden warned oil and gas companies not to raise prices too.

Getting politicians to grok prices has always been a problem, especially in emergencies, but things seem to have deteriorated recently, as the pandemic took hold and inflation reappeared. Now, high prices are a constant political target, price control proposals that we thought had been consigned to the Policy History Dustbin are popping up everywhere, and articles in several major media outlets have gushed about how, actually, price controls worked in the past and can work once again today.

As you can imagine, this turn of events has frustrated and dismayed your humble correspondent, but it hasn’t surprised me: Politicians have a long history of shooting the messenger—almost as long as price controls themselves.

So What Are Prices?

Before we get to that, however, let’s cover briefly what prices are—beyond simply the dollar figure attached to something when you’re buying it. According to the textbooks, when the amount of widgets that consumers demand roughly equals the amount of widgets that producers supply, widget prices in that market will settle at the “the market-clearing price.” So, if a widgetmaker (just go with it) raised his prices above the market-clearing price, he wouldn’t sell all of his widgets, and if he lowered prices below the market-clearing price, he’d run out of widgets and have to turn away customers who still wanted to buy them. Thus, except in very rare circumstances, prices aren’t just some random number a (probably nefarious) profit-seeking company slapped on a good or service; they also reflect what a large number of cost-conscious consumers are willing to pay for it. (“Greedflation” conspiracists please take note.)

But market prices are more than just this balancing act; they (and especially their movements) are a giant neon sign about what’s going on in a particular market. As economist Thomas Sowell explained years ago, “prices are a fast and effective conveyor of information through a vast society in which fragmented knowledge must be coordinated,” and producers and consumers act upon that information:

Prices … not only allow sellers to recover their costs, they force buyers to restrict how much they demand. More generally, prices cause goods and the resources that produce goods to flow in one direction through the economy rather than in a different direction.

As St. Louis Federal Reserve economists recently explained, high prices have two economic functions: First, they allocate scarce goods and services to buyers who are most willing and able to pay for them; and, second, they signal that a good is valued and that producers can profit by increasing the quantity supplied. As part of this, consumers and producers consider alternatives to the expensive good or service at issue: Maybe there’s something that can do what that pricey widget does, only better or more cheaply.

In his excellent book, Economics in One Virus, my colleague Ryan Bourne looks at hand sanitizer during the pandemic to show how prices can work in practice. In particular, the massive and unexpected spike in demand for sanitizer in 2020 hit the current, much lower supply thereof, causing near-term shortages. In a lightly regulated market, prices would then increase dramatically, signaling the relative scarcity of the product, and profit-seeking companies would respond by increasing production, emptying out their inventories, and/or repurposing equipment and facilities to produce sanitizer. Most consumers, meanwhile, would respond by holding back on a second (or 10th) bottle of sanitizer and using alternatives like soap. Gradually, the market would “converge to a position where the supply of sanitizer was able to meet a higher demand at a new, higher price,” and the shortages would soon disappear. Over the longer term, moreover, companies would try to find new and innovative ways to meet higher sanitizer demand, or they might invest in “option ready supply”—i.e., ways to capitalize on unexpected demand spikes in future.

He thus concludes:

In a market economy, then, prices play a crucial role in coordinating economic activity. Not only do they embody a range of information about the underlying state of the market, but their movements provide signals and incentives for economic actors to adjust their behavior in light of that new reality.

In this case, the rising price of sanitizer would have signaled that it was in short supply relative to the huge demand—encouraging producers and merchants to find ways to bring supply to market in order to profit. Only individuals and businesses have the localized knowledge to decide whether they really value obtaining sanitizer or if they could feasibly produce it cost-effectively. The price mechanism provides the incentive for them to change their actions.

Put another way (in a great video series), “prices are signals wrapped up in incentives.” If allowed to float freely, they’ll quickly convey gobs of information to consumers and producers, who will then adapt accordingly. Shortages might not be eliminated, but they’ll be resolved quickly—and everyone will be better prepared the next time.

Going back to my initial examples, a proper understanding of prices shows that the Jones Act folks’ two claims about supply-demand balance and “premium” prices in Puerto Rico both can’t be right: Prices wouldn’t be so elevated if local diesel supply were meeting demand (so, that “illegal” diesel was needed after all). Efforts to discourage “gouging” in Florida or nationally, meanwhile, will likely discourage new suppliers from entering the market at issue, and encourage consumers to hoard—just like they did last year when the Colonial Pipeline shut down and state anti-gouging laws kicked in, resulting in one of the most ridiculous government warnings in the history of Twitter:

Had local gas stations been allowed to freely increase prices, such warnings probably wouldn’t have been needed.

Price Controls’ Long History of Failure

But high prices do, of course, upset consumers—consumers who are also voters that typically don’t like changing their behavior. And politicians have proven all too willing to offer easy “solutions” via price ceilings (e.g., rent control, anti-gouging laws, etc.) or price floors (e.g., minimum wages), treating prices as the problem, not simply a signal thereof.

As the St. Louis Fed explains, however, price caps raise numerous costs:

-

A government bureaucracy and law enforcement must be funded to enforce the controls.

-

Goods and services are allocated inefficiently, both in consumption and production.

-

Competition shifts from production to political markets as firms attempt to influence price-setting decisions.

-

Widespread evasion of price controls promotes disrespect for the law.

-

Suppressed inflation appears when temporary controls are relaxed.

The “allocative inefficiency” is really just a fancy way of saying “shortage” or “surplus” and problems resulting therefrom. Going back to our widgets example, a price cap would increase the quantity of widgets that consumers demand and decrease the quantity that current and potential widget producers are willing to supply. As they note, “Producers would be willing to increase production and sell to consumers who want to buy at a higher price, but price controls make that illegal.”

Thus, we get a widget shortage.

These problems, of course, are not merely theoretical. As Bourne detailed a few weeks ago, for example, World War II price controls not only required an army of bureaucrats and private sector monitors (yikes), but also caused widespread shortages, severely diminished the quality of available goods, and led to deeper black markets. “Adjusting for just some of these factors,” he adds, “Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz believed the effective price level increased by 27 percent during the regulated period.” Nixon-era wage and price controls were similarly disastrous: “Ranchers stopped shipping their cattle to the market, farmers drowned their chickens, and consumers emptied the shelves of supermarkets.” And, of course, inflation persisted.

Fast forward to today and two recent studies of pandemic-era price controls by economists Rik Chakraborti and Gavin Roberts. In the first, they found that the inevitable shortages caused by anti-gouging laws pushed consumers to search more widely for these products, thus increasing virus transmission. The grim result: “After controlling for state population density (which can have a compounding effect on infection), lockdown orders, and other factors, the econometric estimates suggest that price-gouging laws explain at least 25% of the early-April, first-wave Covid deaths in states with such laws.” Their second paper found that consumer searches for pandemic-related goods were stronger in states that already had price gouging laws on the books, suggesting that pre-existing price controls caused consumers to expect shortages (likely based on past experience) and thus hoard and panic buying even more, exacerbating market problems.

Extensive research has also shown that rent control produces similar distortions. Landlords responded to price caps in ways that hurt tenants (especially low-income ones), such as converting rental units into non‐controlled forms of accommodation, such as condos; slowing or ceasing new investments in rental units (thus lowering the overall supply of housing); lowering property quality so that its value more closely matches the controlled rental price; and using “creative ways” to recoup losses, such as new fees for repairs or amenities. And, of course, there are extensive wait lists and black‐market shenanigans—as any Manhattanite knows all too well.

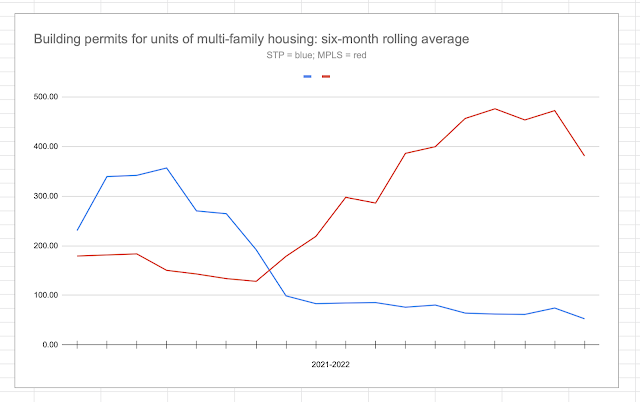

We’re seeing this happen again today in St. Paul, Minnesota, where voters last November approved a “Residential Rent Stabilization Ordinance” that limits monthly rent increases to 3 percent in any 12-month period, effective May 1, 2022. That sparked immediate backlash from local developers, and housing starts there have essentially collapsed. By contrast, next door Minneapolis, which hasn’t implemented its rent control law, saw housing starts increase by more than 200 percent over the same period:

The St. Paul City Council then freaked out and passed an emergency exemption effective January 1, but the damage has clearly been done.

What an utterly-avoidable debacle.

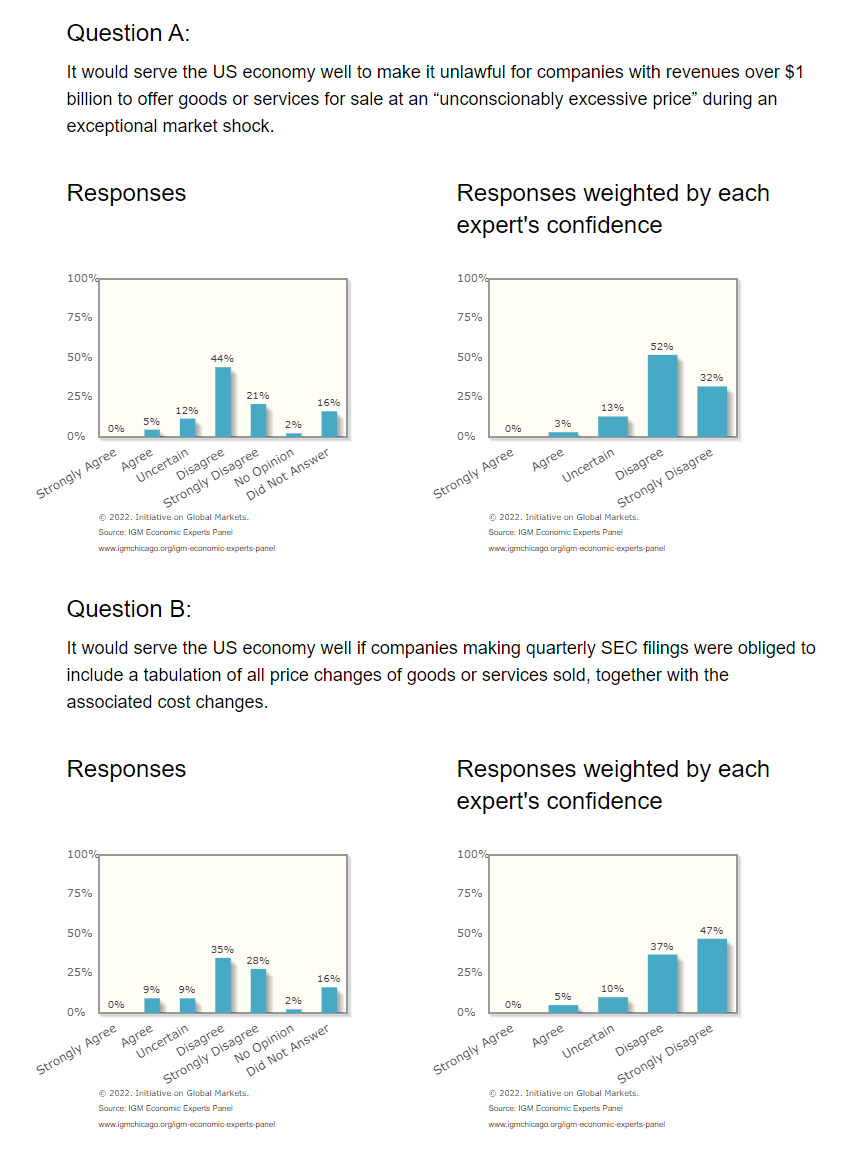

Given this history (and plenty more), it’s no surprise that a recent poll of prominent economists across the spectrum found not a single one “strongly agreeing” with recent federal price control proposals supposedly targeting inflation (ahem, “greedflation”):

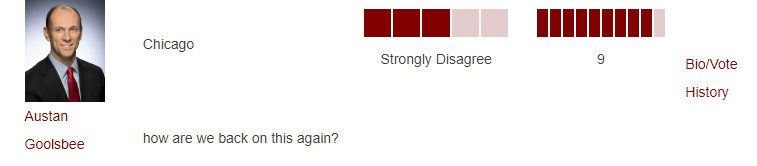

For a humorous look at what most respondents actually thought of this proposal, go check out the comments below the poll. I think the University of Chicago’s Austan Goolsbee, who was President Obama’s CEA chair, speaks for many of us:

So Why Are We Back on This Again?

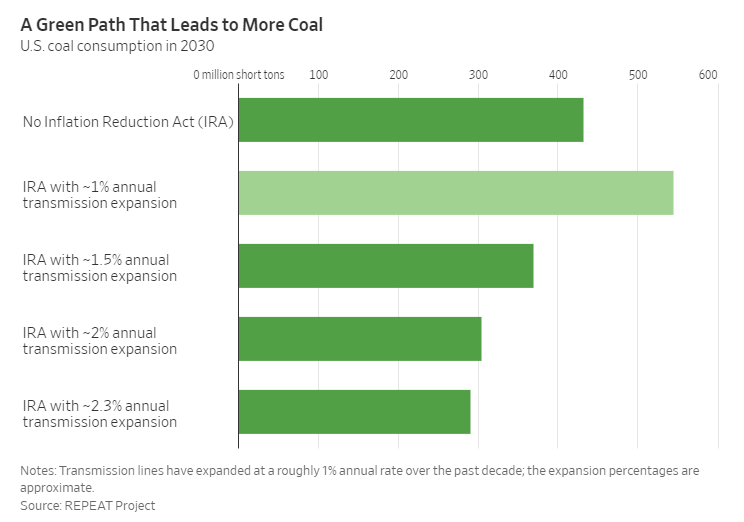

Despite all the research and history, politicians keep trying to control prices and more such proposals appear to be on the way. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, for example, rent control policies are spreading across California, and—as already noted—price controls are getting quite the ahistorical makeover in the media today (sigh). And this occurs despite ample evidence not only that price controls stink, but also that price signals work—even in ways that politicians want. When gas prices recently spiked, for example, American consumers got more interested in hybrids and EVs. High prices for certain “rare earth” minerals like cobalt—used in various renewable energy products—pushed battery producers to develop alternatives that are “safer and cheaper.” Higher energy prices also have encouraged conservation and mitigation, while energy subsidies have done exactly the opposite.

But Goolsbee’s been in politics long enough to know the answer to his (hilarious) rhetorical question: High prices are uncomfortable in the short term, and the next election’s always right around the corner. High prices also tell difficult truths about supply and demand and, more importantly, government policies affecting each. So we see, for example, President Biden and others simultaneously promising massive EV subsidies and strict fossil fuel regulations, while also jawboning oil and gas executives, releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, threatening export restrictions, and doing other things to try to depress domestic gas prices. We see local officials promising rent control after years of denying new building permit applications or expanding exclusionary zoning regulations. And, of course, we see anti-gouging champions shocked and amazed at widespread and persistent shortages of food, fuel, water, and other necessities when a natural disaster strikes.

In case after case after case, letting prices work their magic would provide a better, albeit still imperfect, result (even, as Bourne explains, in emergencies).

As Sowell once said, “Prices are like messengers carrying the news of supply and demand. Like other messengers carrying bad news, they face the danger that some people think the answer is to kill the messenger, rather than taking steps to change the news.” But changing the news is hard, especially when it runs into midterm elections or policy sacred cows. So we instead get a lot of dead messengers, persistent economic obliviousness, and—of course—their terrible, inevitable results.

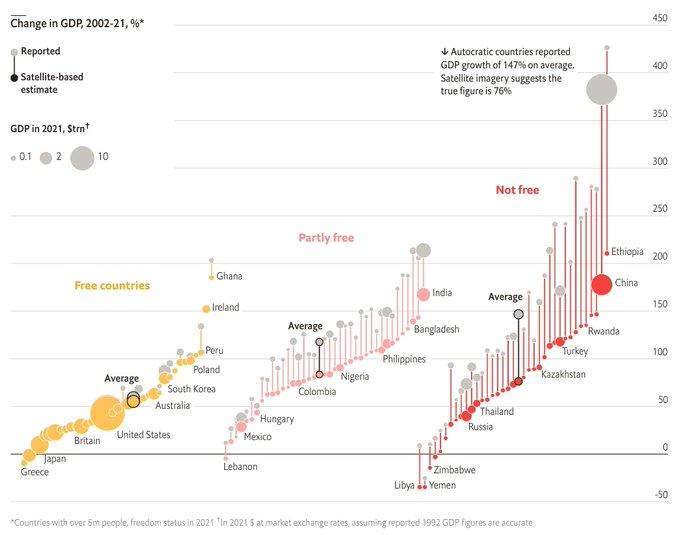

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.