Hello and happy Thursday! Today we mark the 104th anniversary of the downing and death of Baron Manfred von Richthofen (aka, “The Red Baron”).

Today I have a quick take on a petition to Congress as well as a brief(ish) explainer on how China thinks about cyber and how it might be used in a conflict with Taiwan.

A Reasonable Request

A group of former national security leaders has sent another letter to Congress, asking lawmakers to conduct a formal national security review of any pending legislation aimed at “Big Tech.” The signatories include a former director of national intelligence, secretary of defense, secretary of homeland security, and commander of U.S. Cyber Command and director of the National Security Agency. This is like another letter sent late last year on which I also commented.

Here’s the crux of the latest letter:

This is a pivotal moment in modern history. There is a battle brewing between authoritarianism and democracy, and the former is using all the tools at its disposal, including a broad disinformation campaign and the threat of cyber-attacks, to bring about a change in the global order. … U.S. technology platforms have already taken concrete steps to shine a light on Russia’s actions to brutalize Ukraine. Through their efforts, the world knows what is truly happening in cities from Mariupol to Kiev, undistorted by manipulation from Moscow. … Both in public and behind the scenes, these companies have rolled out integrated cyber defenses, rapidly fused threat intelligence across products and services, and moved quickly to block malicious actors on their platforms. This partnership has resulted in the detection and disruption of a series of significant security threats from Russia and Belarus. … In the face of these growing threats, U.S. policymakers must not inadvertently hamper the ability of U.S. technology platforms to counter increasing disinformation and cybersecurity risks, particularly as the West continues to rely on the scale and reach of these firms to push back on the Kremlin. But recently proposed congressional legislation would unintentionally curtail the ability of these platforms to target disinformation efforts and safeguard the security of their users in the U.S. and globally.

Considering this, the authors make one request:

We call on the congressional committees with national security jurisdiction – including the Armed Services Committees, Intelligence Committees, and Homeland Security Committees in both the House and Senate – to conduct a review of any legislation that could hinder America’s key technology companies in the fight against cyber and national security risks emanating from Russia’s and China’s growing digital authoritarianism. Such a review would ensure that legislative proposals do not enhance our adversaries’ capabilities.

It’s obvious this letter is using the situation in Ukraine as an opportunity to push back on pending antitrust and other legislation aimed at “Big Tech.” But that doesn’t mean the concerns, or the request are unfounded (see my previous commentary for more details). In fact, it should be standard operating procedure for these committees of jurisdiction to conduct basic national security reviews of any legislation that might materially affect these interests, let alone an industry that constitutes nearly 10 percent of American GDP.

The request in this letter is not only reasonable, but also common sense. Some might rightly wonder why we even have these defense and intelligence committees if they prove unwilling to exercise oversight on issues so central to their mission.

How China Thinks About Cyber

The events in Ukraine have me thinking, especially the surprising lack of large-scale Russian cyber operations which I’ve written on and spoken of with Steve and Jonah during this week’s Dispatch Live. A lot of folks, including me, are wondering what lessons China might take from these events and, as you noodle on them yourselves, I thought it’d be helpful to give a quick primer on how Beijing thinks about cyber operations and how they might be employed against Taiwan.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) views cyber means as an elemental feature of “informatized” wars, in which information is both “a domain in which war occurs” and “the central means to wage military conflict.” Accordingly, Chinese doctrine locates cyber within the larger operational concept of information operations (IO), which also includes electronic, space, and psychological warfare. Chinese strategists say these are the key capabilities that must be coordinated as strategic weapons to “paralyze the enemy’s operational system of systems” and “sabotage the enemy’s war command system of systems.” In other words: The PLA believes information is the critical resource on the modern battlefield and that victory is achieved by ensuring one’s own access to this resource while denying it to the enemy. IO, then, is a broad operational concept centered on defending China’s ability to collect, use, and share information while also shaping its opponents’ perceptions and ability to complete these same tasks. In the age of digitized data, cyber means are crucial to informatized war.

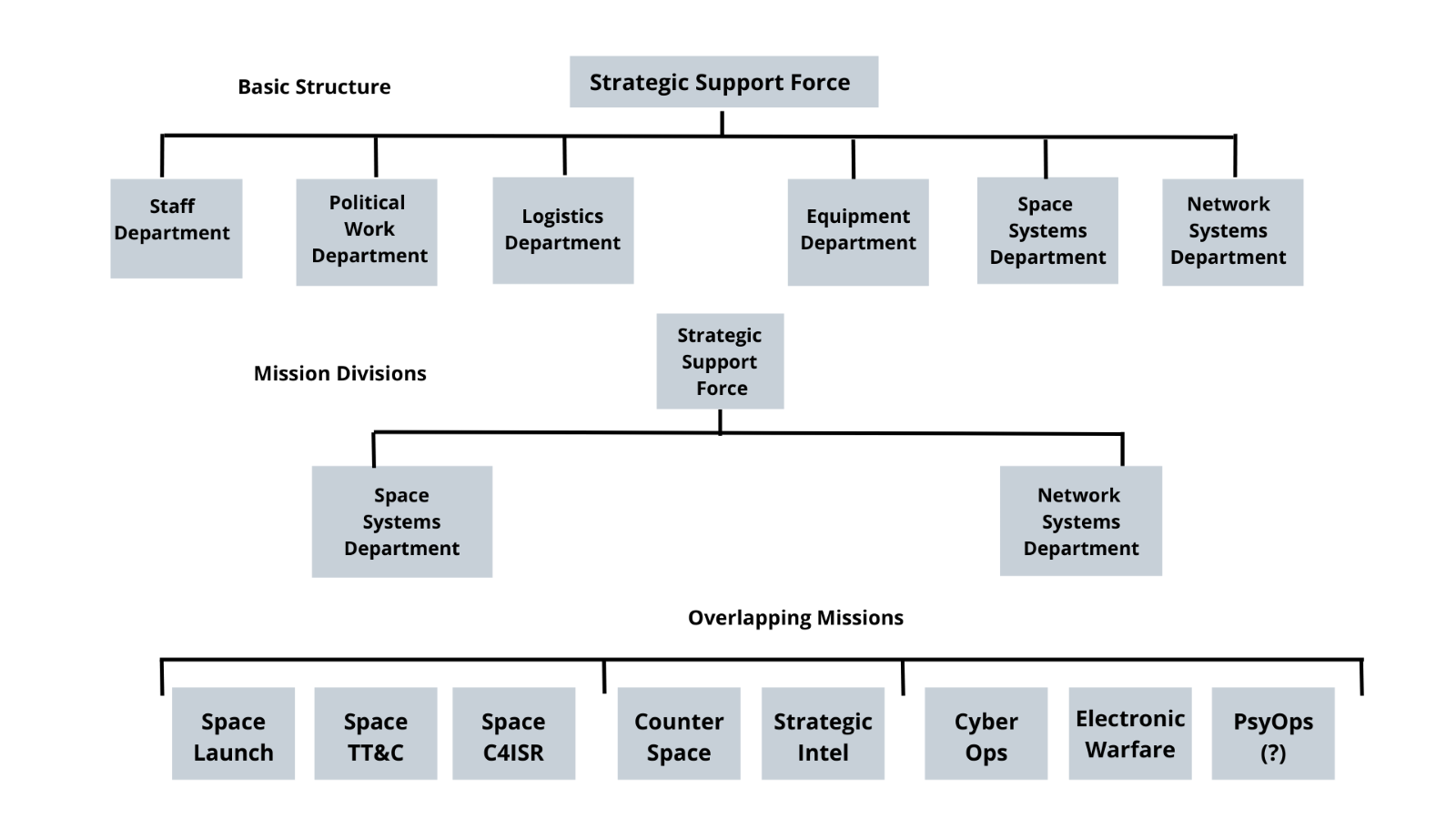

The PLA’s Strategic Support Force (SSF), established in December 2015 as part of China’s extensive military reforms, has primary responsibility for cyber operations. The overall force structure and staffing of the SSF is still opaque, but we do have a basic sense of its operational organization. The SSF consists of two mission fivisions—a Space Systems Department (SSD) and a Network Systems Department (NSD). The SSD has three unique missions: space launch; space telemetry, tracking, and command; and space command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. The NSD also has three missions: cyber operations, electronic warfare, and psychological operations. Both the SSD and NSD share responsibility for counterspace and strategic intelligence missions.

Before this reform, the PLA had a discipline-centric structure in which individual cyber, electronic, space, and psychological warfare units were organized by mission (i.e., defensive, offensive, or reconnaissance). Under this old structure, defensive cyber was handled by the former Informatization Department, offensive cyber was conducted by the Fourth Department (known as 4PLA), and the Third Department (known as 3PLA) managed cyber espionage. The other warfare disciplines were similarly fractured. As the PLA embraced new doctrines for modern warfare, it realized it must also modernize its force structure to effectively prosecute these wars. To this end, the SSF not only unifies these formally disparate elements but also is built around an imperative of “peacetime-wartime integration,” a concept that understands effective cyber warfare does not begin with the onset of official hostilities; it is instead an unending activity that must seamlessly transition between peacetime and wartime.

Pulling this all together: Chinese planners believe it is essential to establish and maintain cyber superiority to enable the full spectrum of informatized warfare, to deter opponents, and to manage escalation. But this superiority, in the minds of PLA planners, is not something that is only looked for in the early days of a conflict, it is an advantage that must be won and leveraged now. It is helpful, then, to think of PLA cyber goals, not as a list of tasks to be completed, but as a collection of ceaseless activities that only vary in intensity based on political requirements.

So, here’s what I think will be the key cyber aims if things go sideways across the Taiwan Strait.

Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) is an SSF core mission and underpins all other cyber activities. Chinese hackers are constantly gaining access to Taiwan’s information systems and networks to better understand China’s targets. Mapping the island’s critical infrastructure and political-military command and control networks are essential aims of these activities. For example, in 2021 China hacked Taiwan’s popular Line messaging service to spy on high-level political officials, military personnel, and city leaders. This had the tangible effect of giving the CCP crucial insight into these communities and the intangible, but still important, effect of undermining these communities’ confidence in the security of their communications.

Operational preparation of the environment. The SSF is also tasked with operational preparation of the environment (OPE). OPE is formally a hallmark of American strategy and doctrine, but its defining features are also present in Chinese planning—particularly in the PLA’s “three warfares”: public-opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare. Cyber operations in support of Chinese OPE include pre-positioning tools and malicious code on vulnerable networks, the development of detailed intelligence and targets related to future military action, and operations intended to have specific effects on the attitudes and behaviors of Taiwan’s citizens and government. All these actions are intended to create an environment that is favorable to China’s goals in peace and war.

Offensive cyberattacks on Taiwan. China’s hackers are also tasked with offensive cyberattacks on Taiwan—actions intended to manipulate, disrupt, or destroy networks, infrastructure, and daily life. During peacetime, these operations assume the form of distributed denial of service, ransomware, and the distribution of other malware. In wartime, these cyberattacks would be more aggressive. Chinese hackers would try to disrupt, degrade, or destroy everything from civilian telecommunications networks to military command and control systems. Air defense systems would go down, power grids would go dark, and essential government services would come to a grinding halt.

Deterring or slowing the American response. Deterring or slowing the American response in support of Taiwan is another key aim for the SSF. These operations would be extremely sensitive and highly influenced by the political context in which they occur. In many ways, Chinese informatized warfare doctrine is crafted specifically with the United States in view, and the SSF already has cyber plans for multiple scenarios. Whatever the scenario, the broad goal would be to undermine the United States’s confidence in its ability to decisively intervene on behalf of Taipei and its ability to do so.

If this all happened tomorrow, how bad could it be? Pretty bad.

Taiwan is catastrophically vulnerable to Chinese cyber aggression. The island’s critical infrastructure, government services, and key military capabilities already endure between 20 million and 40 million cyber attacks every month, with the vast majority of these coming from China. Chien Hung-wei, head of Taiwan’s Department of Cyber Security, says he can defend against most of these attacks but admits “serious” breaches regularly occur. “The operation of our government highly relies on the internet,” explains Chien. “Our critical infrastructure, such as gas, water and electricity are highly digitized, so we can easily fall victim if our network security is not robust enough.” This illustrates China’s chief cyber advantage—scale.

Concrete personnel and budgetary numbers concerning Beijing’s digital forces are not readily available in unclassified channels but estimates range between 50,000 and 100,000 individuals (about the seating capacity of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum), with hundreds of millions of dollars at their disposal. Whatever their actual workforce and funding, FBI Director Christopher Wray has said that “here in the US, [Chinese hackers have] unleash[ed] a massive, sophisticated program that is bigger than those of every other major nation combined.” (Emphasis added.) It can be assumed, then, that similar economies of scale will be employed against one of Xi’s most coveted aspirations—China’s unification with Taiwan.

In early 2001, Taipei set up the National Center for Cyber Security Technology (NCCST), tasked to “establish the cyber security protection mechanism and provide technical services to government agencies, including prior-incident security protection, during-incident early warning and responses, and post-incident recoveries and forensics.” While the NCCST has made notable progress, it is nowhere near the maturity, size, or strength needed for its mission. Relatedly, Taiwan is only on the cusp of building the intragovernmental, industry, and international partnerships necessary for effectively engaging and rolling back the deluge of hostile Chinese efforts online.

None of these critiques are aimed at Taipei’s desires or political will. They are simply a recognition of a threat that even the United States, with its massive resources and capabilities, is utterly failing to mitigate. But hope is not lost, and meaningful improvements can be made in the near term that might dramatically shift the balance in favor of Taiwan.

But there are two concrete steps that we can take to make the situation much better: Harden the homeland and tag team with Taiwan.

First, the United States must continue to harden itself against Chinese cyberthreats to the American homeland and military forces. Taiwan has little to no chance of successfully deterring or preventing a Chinese military attack without American help, and this aid will be severely constrained if the United States does not have a systemic, comprehensive effort to close our own cybersecurity loopholes.

Looking beyond our borders, second, joint cyberwar exercises with Taiwan should be expanded in both frequency and scope. The first of these exercises was held in 2019, but it was hosted by the American Institute in Taiwan—which represents U.S. interests on the island—not the U.S. military. It is now time to synchronize our military cyber operations, because it would be precisely these capabilities that would count in a war with China. While Beijing would certainly protest these exercises, they would not be an act of war and likely would not substantively risk upsetting today’s delicate political equilibrium in the Taiwan Strait. Even if they did, this risk of rising tensions is still preferable to Taipei remaining unable to protect itself against the legions of Chinese military hackers arrayed against it.

Another effective but admittedly controversial action would be for Taiwan to grant U.S. cyber forces direct access to their systems for joint “active threat-hunting” operations. These would involve U.S. and Taiwanese operators working side by side, crawling through the island’s many networks to find and remove Chinese (and other) hostile actors. Certainly, Taipei could be forgiven for any hesitation about allowing such broad access to a foreign country, but China is already in these networks, and bringing U.S. muscle to Taiwan’s cyber defenses could be the difference between crumbling under a Chinese offensive and keeping robust defensive capabilities. The only alternative—trying to hunt down network vulnerabilities at the onset of conflict—would be far too little, too late.

So, to conclude, cyber means are at the heart of China’s emerging military doctrine and will almost surely feature heavily in any attack on Taiwan. In fact, the PLA’s understanding of “peacetime-wartime integration” helps us to see Beijing’s ongoing cyber activities as the early stages of such an effort. While Beijing is a formidable cyber adversary there are concrete steps that can be taken to secure the United States and our friends in Taiwan. Now we must take those steps.

That’s it for this edition of The Current. Be sure to comment on this post and to share this newsletter with your family, friends, and followers. You can also follow me on Twitter (@KlonKitchen). Thanks for taking the time and I’ll see you next week!

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.