This week the Biden administration began ramping up its efforts to get social media companies to crack down on vaccine disinformation online. I won’t spend too much time summarizing the twists and turns of the debate, but White House spokesperson Jen Psaki argued for expanded bans for misinformation, saying, “You shouldn’t be banned from one platform, and not others,” President Biden accused Facebook of “killing people” (before walking the comment back), and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called online conspiracy theories an “urgent threat to public health.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about this issue—including why I’m so uneasy about the administration’s rhetoric. Yes, if government persuasion (or scolding) turns to coercion, there are obvious First Amendment implications. The White House doesn’t get to dictate social media moderation decisions. But my objection is deeper. The administration’s argument misreads the situation.

In fact, it was a bit odd to see the administration lash out at social media companies when they have already taken action to limit the spread of vaccine disinformation. You can read Twitter’s policy on vaccine misinformation here, Facebook’s policy here (disclosure: The Dispatch is part of Facebook’s fact-check program), and YouTube’s policy here. They’re broad, expansive, and frequently enforced. Spend nine seconds on right-wing media, and you’ll see angry story after angry story about social media censorship. The current rule is not anything goes.

Partisans fight so much over Big Tech that it seems they forget that there are varied and vast networks of communication outside of social media. In fact, there are circumstances where “deplatforming” a person can make him or her more famous, as they launch a media tour to complain about Big Tech intolerance.

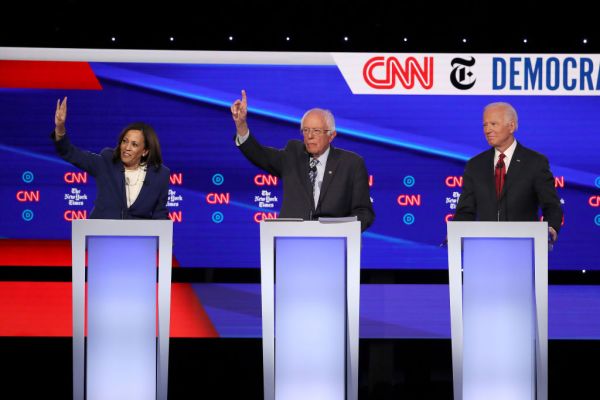

In addition, as Stanford’s Renee DiResta notes in a truly informative tweet thread, many of the most influential purveyors of vaccine disinformation have large, independent platforms. Cracking down on social media won’t stop Tucker Carlson from booking Charlie Kirk on his show for segments like this:

It’s also the case that reporting about vaccine misinformation amplifies vaccine misinformation. I’d never heard the absurd claim that the vaccine magnetized the human body until I saw it on a media report.

What does this all mean? I agree with this, from Sara Fischer and Scott Rosenberg in Axios: “Once the COVID vaccine topic became politicized, the effort to limit misinformation became infinitely harder.” I’ll actually go farther. Once the response to COVID itself became politicized—with Republicans underestimating the risks of COVID and Democrats overestimating them—the die was cast. The instant that the response to COVID became part of the culture war, every single preventative measure was going to be contentious, including the vaccine.

Thus, misinformation isn’t necessarily the cause of vaccine hesitancy so much as it’s the rationalization for vaccine hesitancy. Even in communities where the COVID culture war isn’t an explanation for reluctance—like in more-hesitant minority communities—the true task isn’t so much overcoming misinformation as overcoming a pre-existing posture of distrust that the misinformation latches onto.

So long as the culture war lasts (or so long as the distrust persists) dealing with misinformation is like playing a form of psychological whack-a-mole. Debunk one objection and another pops up, often until the objections aren’t factual at all, but exposed as rooted in something else entirely. There’s perhaps a sense of defiance, an appeal to freedom, or a fear that manifests itself in a kind of deep dread.

Let’s be honest. Americans have been deluged with positive information regarding the vaccine. With few exceptions, every single significant elite entity of American persuasion has been directed at the American public. Social media companies have supplemented a comprehensive campaign against misinformation with a comprehensive campaign for the vaccine. I can’t log onto Facebook without the site offering me vaccine resources.

I’m not saying we should stop. I was glad to see a number of Republican politicians and Fox News urge their constituents and viewers to take the vaccine. This statement, by Ron DeSantis, was particularly good:

But I wonder if the top-down persuasion effort has reached the limits of its effectiveness. All the low-hanging fruit has been plucked. Now we’re at the phase of the fight that’s person-by-person and family-by-family.

That’s one reason why I was flummoxed by the vitriolic online response to my friend Michael Brendan Dougherty’s recent National Review piece on vaccine hesitancy and public persuasion. He wrote a thoughtful essay that simply suggested that vaccine advocates shouldn’t condescend to or express contempt for the vaccine hesitant, but rather meet them where they are and address their concerns with respect and understanding. Here’s a key paragraph:

To understand vaccine skeptics, proponents need to understand that the skeptics typically don’t fear COVID. They may fear that taking the vaccine is, in some way, to consent to the view that their freedoms are dependent on compliance with public health. Arguing that the vax is the path back to normality and fewer public-health restrictions backfires with skeptics, in my experience. They see consent to this view as a promise to willingly go under house arrest once a new variant hits the front-page headlines again. For them, excessive fear of COVID is the primary cause of public-health restrictions, and their refusal to take the vaccine is, in some small way, an attempt to model a life unruled by this fear.

In response he endured days of, you guessed it, condescension and contempt. But why? There have, indeed, been measures (including, most notably, persistent school closings) that have been motivated by an excessive fear of COVID. The very people who decry misinformation have often fallen for misinformation themselves. Longtime proponents of outdoor masking, for example, are not the best folks to scream “Science!” in the faces of the vaccine reluctant.

Moreover, wars on misinformation are dangerous for free speech. Turning to the government to define misinformation is especially dangerous. It can sometimes even be dangerous for public health. Remember this infamous statement, from none other than the former surgeon general of the United States?

Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS!

They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!

That was February 29, 2020, and if that particular government line became the unified approved message across the length and breadth of social media, the public health damage would have been even greater than early mixed messaging on masks proved to be.

Let’s presume the surgeon general was acting in good faith. But it takes only a grade school knowledge of American history to know that the government officials have been a source of intentional misinformation, repeatedly, throughout American history. Should social media companies listen to government officials? Sure. Should they accept their judgments as the last word? Never.

Even setting aside the possibility of government corruption or incompetence, misinformation is often difficult to define even for competent individuals putting forth their best efforts to discover the truth. Early assessments can prove wrong. Remember the consensus that the lab-leak theory was misinformation? Remember the efforts to rule it out of bounds?

In the midst of complex, evolving, and fast-moving events, we should be more reluctant to apply the misinformation label, not less. That’s doubly true in a low-trust time. And we should not let the relative ineffectiveness of existing efforts to ban misinformation lead us to believe that we just haven’t censored enough.

The free speech advocate in me says that in the face of continuing, widespread resistance and confusion, the answer isn’t “censor more.” It’s “say more.” Persuade. But really that’s only part of the answer. It’s also “engage more,” at the personal level. Don’t delegate your community’s health to the words and actions of government, corporate, or media power. Deep distrust is best dispelled personally, through relationships, words, and actions.

My favorite persuasion story comes from a friend. His mom refused the vaccine. She said she’d never take it. He tried everything. He begged. He pleaded. He sent fact checks. Finally, he played his last card. “Mom,” he said, “If you take the vaccine, I’ll stop dipping.” He’d give up his snuff if she got her shot. It worked. She’s vaccinated.

Without letting up one inch in public persuasion, it’s time for all of us to take personal responsibility. It’s our job to get the shot, and it’s our job to directly reach those people in our lives who express reluctance. Not in scorn or condescension, but with compassion and respect. That was and is our best path through this terrible plague.

One last thing …

Dune. Trailer Two. Glorious:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.