In my entire adult life I have never seen so many people at one time fall for the most transparent and dangerous of lies. Yes, I’m talking about QAnon. I’m also talking about “stop the steal.” I could also talk about a host of other lies (remember when “hands up, don’t shoot” helped trigger violence in cities across America?) It’s as if our culture’s very ability to discern truth is breaking, and—as we saw on January 6—the consequences are already catastrophic.

In fact, as I speak and write about American division and polarization, one of the single most common questions I receive is simple and heartfelt—“How do I reach friends and family members deceived by lies?” Parts of Washington may want to move on to old-fashioned fights about policy, but millions of families are still dealing with the existential anguish of believing that America is over and that democracy is dead.

The challenge is so great that I agree with Slate’s Will Saletan: The most important battle in American politics isn’t between right and left, but between truth and lies. Earlier this week, he wrote a powerful piece reflecting on the Trump years. It began with this paragraph:

Over the years, I’ve bounced around the political spectrum. I was liberal in Texas, more conservative in college, and now I’m somewhere in the middle. Through it all, I saw politics as a fight between left and right. I don’t see it that way anymore. Donald Trump’s presidency has exposed a bigger threat: an all-out attack on the principle that facts must be respected. We used to take that principle for granted; now we must defend it. Politics has become a fight between those who are willing to respect evidence and those who aren’t.

Think of the difference in American politics if we operated from basic truths. The president was lawfully elected. America’s political elite isn’t overrun with pedophiles. Dispelling pernicious falsehoods can substantially lower the temperature of public discourse. It can help us breathe. It can render us less vulnerable to demagogues and repair broken families and restore lost friendships.

What is to be done? Can anything break the fever?

I’ll be honest. There are no easy answers. But we can think about the market for lies according to the principle of supply and demand. A demand for news that confirms our biases creates incentives for bad actors to give the public exactly what it wants. Injecting lies into the public square creates its own hysteria and feeds new demand.

On the demand side, the best path forward is to engage first with the conspiracy-curious—the person who’s not yet all-in. They’re the people most likely to be helped when you answer bad speech with better speech. Each of us has to try, patiently, faithfully, and as kindly as we can to pull friends and relatives back into reality. Take even the most bizarre questions about American life—so long as they’re asked in good faith—as an opportunity to engage.

The conspiracy-committed, however, are a far tougher nut to crack. In fact, direct engagement with such people can be counterproductive. Disagreement only identifies you as an enemy. So when it comes to the most lost among us, it’s prudent to shift our gaze from the demand side of the disinformation equation (the conspiracy-theory public) to the supply side (defamatory conspiracy theory media). And here we have tools to respond.

In this newsletter and in Time I’ve written about how social media giants should default to protecting free speech on their platforms but must also maintain basic guardrails: If lies metastasize into violence, American companies can and should exercise their liberty to prohibit seditious liars from accessing their platforms.

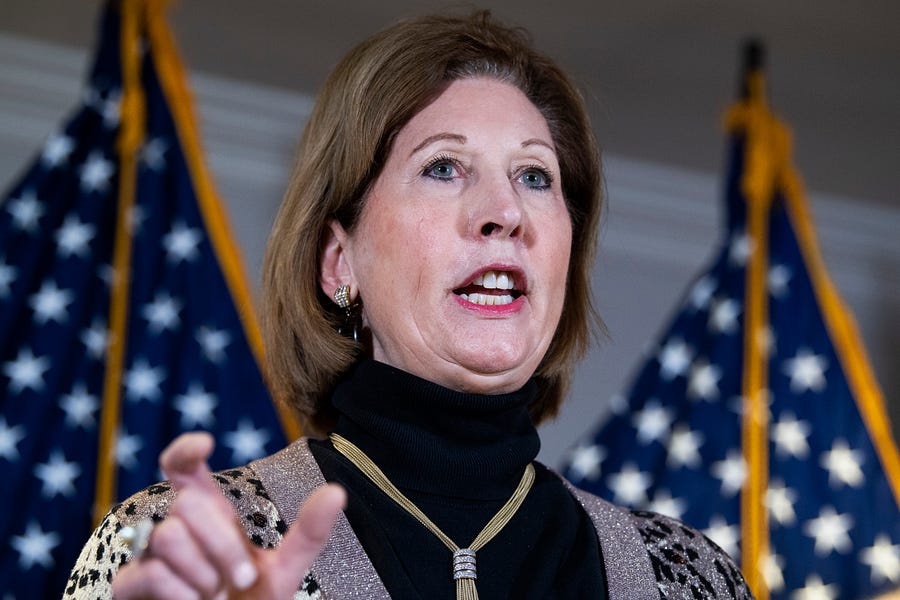

But more can be done. More is being done. These last few weeks have seen important legal developments in the fight against dangerous lies. First, and most famously, Dominion Voting Systems has begun its legal counterattack against many of the worst falsehoods of the post-election season. It has sued both Sidney Powell and Rudy Giuliani for defamation, and it’s likely to follow these cases with additional lawsuits—perhaps even cases aimed at the biggest titans in conservative media.

Second, last week the Texas Supreme Court rejected Alex Jones’s attempt to throw out lawsuits filed against him by parents of children murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary. He’d claimed no one had died at the school. He’d claimed that distraught families were faking their pain: “I’ve looked at it and undoubtedly there’s a cover-up, there’s actors, they’re manipulating, they’ve been caught lying and they were preplanning before it and rolled out with it.”

Third, Fox News agreed late last year to pay “millions of dollars” to the family of slain Democratic National Committee staff member Seth Rich after the network repeatedly published and broadcast reports that falsely tied Rich to the DNC email leak during the 2016 campaign.

These developments come on the heels of an important 2019 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals decision reviving Sarah Palin’s defamation claims against the New York Times after a Times editorial falsely tied Jared Lee Loughner’s mass shooting and attempted murder of Representative Gabrielle Giffords to a map Palin’s political action committee published “targeting” Giffords for political defeat with an image of a crosshairs. There was never any evidence Palin’s map or Palin’s speech played any role in Loughner’s attack.

I must confess that part of me is uncomfortable with each of the events above. Social media moderation decisions can sweep too far. Defamation cases are subject to abuse, and deep-pocketed, vexatious litigants can use lawsuits to attempt to silence opposition. Exposing lies should discredit the liars. But we don’t live in the world that should exist. We live in the world that is, and in that world, there are times when the legal hammer simply must fall.

Free nations need legal guardrails, and defamation, properly defined, has never been deemed part of “the freedom of speech” the First Amendment protects. Legal rules against defamation, incitement, and true threats are among the indispensable safeguards that protect America’s experiment in ordered liberty.

Just after the January 6 Capitol attack, I discussed the concept of “separating the insurgents from the population.” By that I meant precisely using the instruments of law to impose legal consequences for unlawful action while also engaging in good faith and open hearts with the vast bulk of the population that isn’t fully committed to its false narrative. Persuasively diminish the demand for defamatory conspiracies. Lawfully constrict the supply.

There is no magic medicine that will cure our cultural and political disease, but I agree with Saletan: the battles between right and left—as important as they are—are ultimately less consequential than the fight between those who seek earnestly and humbly seek truth and those who angrily and self-righteously embrace the most dangerous lies.

One last thing …

Readers, help me. I can’t decide if this movie is going to be good. Godzilla (2014 version) was great. Kong: Skull Island was solid. Godzilla: King of Monsters was a disappointment. So, tell me, will Godzilla v. Kong be good? Render your verdict below.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.