Yesterday my friend Jonathan Haidt published an essay that defines the term “must read.” Called “Why the past 10 years of American life have been uniquely stupid,” it traces social media’s influence on the decline and fall of American institutions. I don’t want to spend too much time summarizing his argument (it might prevent you from reading his piece), but its critical contribution to the debate is explaining exactly how social media’s features have connected with our own human nature to produce the cultural and political sewer we inhabit today.

I’ve long resisted the urge to over-blame social media for our present ills. As I’ve said in countless speeches and book talks since I published Divided We Fall (out in paperback!) Americans have long proven that we’re fully capable of ripping each other to shreds without Twitter. But it’s also true that new technologies create new challenges, and can enhance the worst aspects of our human nature in novel and terrible ways.

(Think, for example, of all the ways the printing press upended the medieval world, or how the industrial revolution revolutionized both the world economy and world war.)

In each case, we couldn’t stop technological change, but we did have to adapt to it, to the point where—at the end of the cultural evolution—the new world was ultimately better than the old. The question we have now is whether we can adapt to social media before it facilitates a cultural calamity on the scale of the industrial revolution’s two world wars.

But rather than take on how we use all of social media in one newsletter, I want to focus on the platform of choice for the vast majority of America’s political elite—Twitter—and how we’ve allowed it to contribute to the degradation of journalism, politics, and (to some extent) the academy.

The short answer is that it’s hard to think of a platform better designed to magnify our human weaknesses and minimize our strengths than Twitter. In the flagship Advisory Opinions podcast, Sarah and I are fond of reminding listeners that “judges are people too.” Thus, when analyzing court arguments and judicial opinions it’s always wrong to think of judges as jurisprudential robots, spitting out opinions in accordance with preset jurisprudential programming.

Well, journalists are people too, and our dedication to Twitter carries with it unique perils along with a few key benefits that make it extremely difficult to abandon the platform entirely. Let’s chronicle some of the problems, beginning with the obvious:

Impulsiveness. There is not a word I publish at The Dispatch or The Atlantic that isn’t read by a smart editor, who often pushes me on my reasoning and my language. Here at The Dispatch, our very own Andrew Egger edits me more than anyone else, and believe me, he feels very free to tell me when or where my logic fails or my argument is unsupported.

Thus each essay at the very least has been reviewed by one other set of eyes. It’s been scrubbed of its worst arguments and its obvious mistakes. In short, I’m at my best when I’m edited. But Andrew’s not reading my tweets. There’s no layer of fact checkers, and typically no one is around to help you wordsmith difficult ideas.

As a profession, we’ve accepted that not one published word will be unedited, except on the very platform where millions of people first encounter our work. That’s a problem.

Insecurity. This might surprise you, but lots of writers and journalists suffer from some version of imposter syndrome, that vague sense of dread and insecurity that tells you that you’re a fraud, that no one should listen to you, and you’re one bad essay or one bad piece from being revealed.

The result is that writers often crave positive feedback and recoil like they’ve been poked with a cattle prod when they’re subjected to online pile-ons. The natural human tendency is to seek out allies, to write for allies, and to wall yourself off from opponents. Any other approach leaves you vulnerable to the “darts of social media,” the memorable phrase Haidt uses to describe the ways in which we punish our political opponents.

Ambition. Twitter is very, very effective at delivering fifteen minutes of fame. A single good tweet can land someone a prime time cable news hit. A good tweet thread can generate a call from an editor asking you to turn it into an op-ed. And because an enormous amount of political and cultural content is generated by young writers at online publications who live on Twitter looking for witty or angry or offensive tweets to write about, there’s an incentive to constantly punch and poke at bigger names or bigger accounts to gain attention.

Indeed, shrewd trolls know that insecurity can feed ambition. Poke at a person long enough, and they just might respond. Trolls know that cruelty hurts, and it often “works” by generating a public reaction, and that public reaction perversely enough not only grants the troll greater reach and visibility than he ever had before, it elevates and spreads their underlying insult.

Thus, in a strange way, a public figure can quite literally harm his reputation by defending his reputation.

Pride. This is the flip side of insecurity, and it’s one consequence of walling yourself off from your critics. Not everyone suffers from self-doubt, and Twitter lends itself to impulsive opinion-making, especially in the midst of breaking news. “My followers want to hear from me” (which is only sometimes true) can morph into “my followers need to hear from me” (which is virtually never the case).

The result is that the temptation to speak can be overwhelming, and this temptation is often fed by trolls or critics, who for their own purposes might declare that your “silence is deafening” or that “silence is complicity” when you don’t respond to the topic of the day.

But there’s obvious danger in freely expressing your thoughts. Most of us have deep knowledge about a narrow set of topics and shallow knowledge (at best) about most everything else. Speak constantly and you will expose your ignorance. It’s guaranteed.

Alcohol. Journalism and politics are hard-drinking professions, and one of the worst-kept secrets of social media is that an immense amount of nighttime content is drafted and sent while under the influence. Does someone seem oddly angry? Does their expression feel just a bit “off” compared to their normal words? That’s the bourbon talking.

Combine some level of drunkenness with a lack of editing, vanity or insecurity, and the ambition and attacks of critics, and the results can be gruesome.

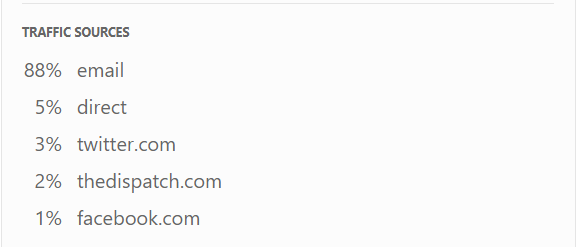

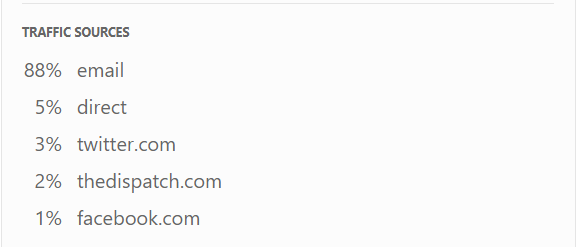

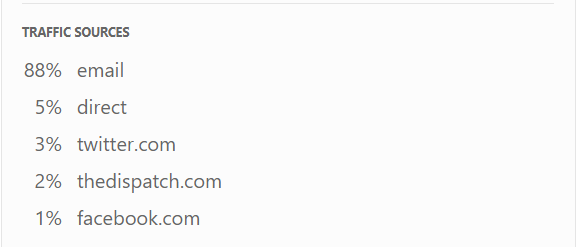

Now I’m going to lift up the hood a bit and let you see why it is both true that journalists should transform their relationship with Twitter and why it is so hard to remove yourself entirely from the platform. First, I’m going to show you typical traffic sources for one of my Sunday newsletters:

Look through newsletter after newsletter, and you’ll see the same thing—Twitter delivers between one and five percent of all traffic. Here are the sources for the most viral piece I’ve written at The Dispatch:

So why not leave Twitter? Why on earth would you expose yourself to the abuse and the quick hits and the potential reputational pitfalls of bad tweets? Well, as Megan McCardle recently wrote, there’s a collective action problem here. Twitter is where your peers are. It’s how they gain instant access to your work and thoughts and you gain access to theirs.

Moreover, once you know who to follow, there is no better platform for tracking breaking news. (Of course, the flipside of this is that if you’re following the wrong people, your feed can be a firehose of disinformation and bad faith.)

If you want to see the promise and peril in one graphic, look at the analytics for one of my own viral tweets that promoted a Sunday essay. First, here’s the tweet. It was provocative. It got the people going:

The tweet promoted a piece that discussed the sad reality that thousands of Christians were packing churches across the nation to hear from dangerous political radicals. I documented threats from church stages and the Christian sponsorship of a sold-out tour that featured Michael Flynn—Donald Trump’s former national security adviser—who had called for military intervention in the 2020 election.

Here are those tweet’s analytics, and they demonstrate exactly why journalists do and do not want to be on Twitter:

Impressions roughly count how many times a tweet is seen. Engagements count interactions with the tweet. The tweet earned more than 2 million views (2,050,836, to be precise). That’s just one tweet! That kind of reach is why people covet virality. But wait. Clicks represented only 0.3 percent of total impressions.

The end result is that an immense number of people saw one small thought, the short tease of an almost 2,100 word essay. And that short tease earned me no small amount of fury online.

Different social media platforms grab different Americans in different ways. For the American cultural and political elite, Twitter is Walter White’s blue meth from Breaking Bad. It grants a unique high for a unique population, the instant access both to the information and feedback that so many of us crave. But once the addiction sets in, all too many of us become our worst selves—transmitting our insecure (or prideful) unedited thoughts into a platform full of people who are salivating to destroy reputations and earn fame.

It’s a wonder that journalism has any credibility left. It’s time to adapt to the platform or leave it entirely. Twitter beclowns the American elite. Or, more precisely, Twitter helps us beclown ourselves.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.