In March, when state and local governments began sweeping, comprehensive lockdowns in response to the emerging coronavirus pandemic, millions of Americans had an urgent constitutional question. Can they do that? Do governments have that much power to respond to an infectious disease?

It was a logical question. After all, virtually every living American had grown up in the era after we’d largely conquered infectious diseases. It’s not that we didn’t get sick, or that (for example) flu seasons couldn’t get serious, but the idea of a disease ripping through our communities and killing hundreds of thousands of Americans in a matter of weeks was utterly alien to our experience.

But it wasn’t alien to our national or constitutional experience. And indeed there exists a body of constitutional case law—dating back to the founding generation—that acknowledges the police power of states to respond to pandemics, including by passing quarantine laws and “health laws of every description.” Perhaps the best example of the Supreme Court’s “pandemic” law comes from a 1905 Supreme Court case called Jacobson v. Massachusetts.

In Jacobson, the plaintiff challenged a compulsory vaccination requirement in the midst of a smallpox epidemic. The court ruled for the state. First it noted the “paramount necessity” of the state to provide for the “self-defense” of the citizens “against an epidemic of disease”:

The authority to determine for all what ought to be done in such an emergency must have been lodged somewhere or in some body, and surely it was appropriate for the legislature to refer that question, in the first instance, to a Board of Health, composed of persons residing in the locality affected and appointed, presumably, because of their fitness to determine such questions. To invest such a body with authority over such matters was not an unusual nor an unreasonable or arbitrary requirement. Upon the principle of self-defense, of paramount necessity, a community has the right to protect itself against an epidemic of disease which threatens the safety of its members.

Given this necessity, the court would defer to state regulations unless they were “arbitrary” and “not justified.”:

Smallpox being prevalent and increasing at Cambridge, the court would usurp the functions of another branch of government if it adjudged, as matter of law, that the mode adopted under the sanction of the State, to protect the people at large was arbitrary and not justified by the necessities of the case.

More:

There is, of course, a sphere within which the individual may assert the supremacy of his own will and rightfully dispute the authority of any human government, especially of any free government existing under a written constitution, to interfere with the exercise of that will. But it is equally true that, in every well ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.

Thus, the court granted broad deference to state authorities so long as their rules had a “real and substantial relationship” to public health.

To be clear, this is far from the normal test applied to state infringements on constitutionally protected liberties. Typically, state attempts to regulate and inhibit the exercise of, say, First Amendment rights are subject to far more exacting scrutiny.

But since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, multiple courts—including the Supreme Court—have referred back to Jacobson to uphold draconian state lockdown regulations. For example, earlier this month the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals turned back the Illinois Republican Party’s attempt to overturn the state’s restrictions on large gatherings and held that, “At least at this stage of the pandemic, Jacobson takes off the table any general challenge to EO43 based on the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of liberty.”

In South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, a 5-4 majority of the Supreme Court rejected a church’s challenge to California’s lockdown regulations, relying in part on Jacobson. It granted state officials wide latitude to enact public health regulations:

When those officials “undertake[ ] to act in areas fraught with medical and scientific uncertainties,” their latitude “must be especially broad.” Where those broad limits are not exceeded, they should not be subject to second-guessing by an “unelected federal judiciary,” which lacks the background, competence, and expertise to assess public health and is not accountable to the people. (Citations omitted).

But here’s the key question. How long should that latitude last? Should it last through the entire length of any given pandemic or only so long as the “fraught” medical or scientific uncertainty endures?

On Monday, Pennsylvania federal district court judge William Stickman briefly sparked a furious legal debate with a lengthy ruling striking down a number of Pennsylvania pandemic regulations. The truly interesting part of the opinion wasn’t his granular analysis of the Pennsylvania rule but rather his rejection of Jacobson. Essentially, Judge Stickman said, “Enough!” It’s time to return to regular constitutional order.

To justify his decision, Judge Stickman referenced Justice Alito’s dissent in Calvary Chapel v. Sisolak. In Calvary Chapel, the Supreme Court rejected a church’s effort to enjoin Nevada’s restrictions on church gatherings. The court issued its decision almost two months after South Bay, and it upheld (for now) regulations that were quite discriminatory against religious worship. Nevada granted casinos far more freedom than it granted churches, an dAlito was not impressed:

For months now, States and their subdivisions have responded to the pandemic by imposing unprecedented restrictions on personal liberty, including the free exercise of religion. This initial response was understandable. In times of crisis, public officials must respond quickly and decisively to evolving and uncertain situations. At the dawn of an emergency—and the opening days of the COVID–19 outbreak plainly qualify—public officials may not be able to craft precisely tailored rules. Time, information, and expertise may be in short supply, and those responsible for enforcement may lack the resources needed to administer rules that draw fine distinctions. Thus, at the outset of an emergency, it may be appropriate for courts to tolerate very blunt rules. In general, that is what has happened thus far during the COVID–19 pandemic.

But a public health emergency does not give Governors and other public officials carte blanche to disregard the Constitution for as long as the medical problem persists.

Note clearly Alito’s sliding time scale. When the crisis is unfolding—and confusion and uncertainty are at their greatest—deference is defensible. But as the confusion eases and we gain more knowledge, that deference should fade. Or, as Alito argued, “As more medical and scientific evidence becomes available, and as States have time to craft policies in light of that evidence, courts should expect policies that more carefully account for constitutional rights.”

Yes, this is a dissent, but in principle Justice Alito is exactly correct, and I’d wager a vast sum of money that most of his colleagues also agree. They just disagree on when the uncertainty is sufficiently resolved to reimpose conventional constitutional order. In other words, a time will come when deference should fade and scrutiny should begin.

Judge Stickman argued that the time should be now. “It is no longer March,” he writes (it’s also no longer July, when SCOTUS ruled in Calvary Chapel), “It is September and the record makes clear that Defendants have no anticipated end-date to their emergency interventions.” To be clear, arguing for greater scrutiny is not the same thing as arguing that there’s no constitutional reason or constitutional room for prudent health regulations. Instead, it’s a declaration that to justify draconian restrictions, states are going to have to establish that those restrictions meet traditional constitutional tests.

That is not too much to ask. After all, every serious scholar grants that states have a compelling public interest in mitigating the spread of a deadly disease, but now that we know far, far more about the way in which the disease is transmitted, the effectiveness of various defensive measures (like masks), and the demographics of vulnerable populations, states and cities should be required to prove that their regulations achieve the desired ends through the least restrictive means.

The period of true confusion is over. The time of trust and deference must come to an end. The fog of war is lifting, and we can see our viral enemy with far greater clarity. Let’s put “pandemic law” back on the shelf. Ordinary constitutional scrutiny is sufficient to protect both our lives and our liberty.

One more thing…

There’s another review of my book out in the world. And this one is … interesting. Douglas Perry says I “fear secession” but also “make a strong case for it.” He says my short-term pessimism about mutual hatred and intolerance makes the argument for division:

“So, is there hope for tolerance to break out?” [French] writes. “… Will cultural antibodies emerge to save the body politic from the disease of negative polarization? Frankly, I’m not optimistic. In part it’s because the tolerance that’s indispensable to pluralism requires a degree of political and moral courage, and in modern America that kind of courage is in short supply.”

This sure sounds like an argument for secession. And why not? Without question, a lot more Americans would end up being happy with their federal government if the United States broke up into, say, five independent countries. A lot fewer Americans would have to put up with public policies and federal court decisions they don’t like.

Nope, it’s not an argument for secession. It’s an argument that we should wake up and realize how our own fear and hatred are undermining our national union. We wrongly take our unity for granted and consequently stoke fires of rage that have fractured nations before.

Read the book for yourself. Do you think I make secession sound remotely desirable?

One last thing …

I think I’ve read the book The Right Stuff five or six times. I’ve seen the movie at least as often. Both of them are classics. Both of them capture a core truth about heroes—and the men who are the heroes of the heroes.

I was today years old when I learned The Right Stuff is about to be a Disney/National Geographic television series. Will it be good? Here’s the trailer. Does it fill you with excitement, or dread?

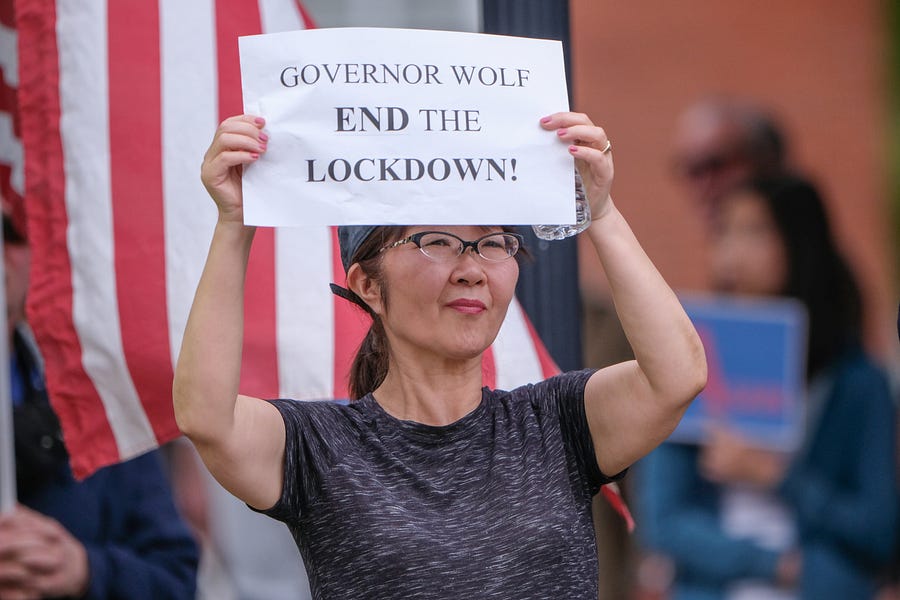

Photograph by Preston Ehrler/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.