On Sunday, March 28, my wife and I published a comprehensive report providing new details about what we called “the worst Christian sex abuse scandal you’ve never heard of.” It was the story of a superpredator (Pete Newman) who sexually abused boys for a decade or more at one of the largest Christian camps in the nation, Kanakuk Kamps. Our report detailed what the superpredator did, and it also described what the camp knew and how it responded to multiple reports of misconduct before his arrest.

We spent months working on the report. We combed through court records, we interviewed witnesses, and we interviewed victim’s families and victims. We also obtained and published, for the first time, deposition transcripts, deposition videos, and internal camp documents directly related to the case.

During our investigation, a troubling pattern emerged. Victims and their families expressed fear of the camp. They told stories of hardball litigation tactics, deceptive communications with camp officials, and unwanted contact with the camp’s CEO, Joe White. In fact, one victim’s family even filed a motion for restraining order to stop White from contacting their son.

Why bring this up? Because I read with real interest Kanakuk’s letter to families in response to our recent reporting. In addition to calling our narrative “inaccurate, incomplete, and misleading” (more on that later), it contained the following paragraph about nondisclosure agreements. Here’s Kanakuk:

Recent articles have accused Kanakuk of using Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) to hide details of abuse and silence victims. This is simply not the case. The awful details of what transpired is part of the public record. The criminal component was equally public and local television stations and newspapers covered this for many months. Kanakuk’s focus is on supporting victims’ privacy and healing. The overwhelming majority of confidentiality agreements were established in cooperation with the victim to protect their privacy.

There was a reason why Kanakuk used the phrase “overwhelming majority” to describe the alleged amount of cooperation with victims. The cooperation wasn’t universal. In at least one case Kanakuk tried to force a victim and his family to sign an agreement against their will, and they sought to punish the family with thousands of dollars in fines when they refused to agree to Kanakuk’s terms. We’ve obtained documents that illustrate the very “hardball” the victims warned us against.

The story, drawn from the documentary record, interviews with the victim’s family, and Kanakuk’s own court filings, is relatively simple. During a mediation in the case, the camp, the victim, and his family allegedly reached a mediation agreement that included the phrase: “Final settlement agreement will contain a mutual non-disparagement clause, in mutually agreeable form.” A non-disparagement agreement is a form of nondisclosure agreement that prohibits signatories from publicly sharing derogatory information about their counterparts.

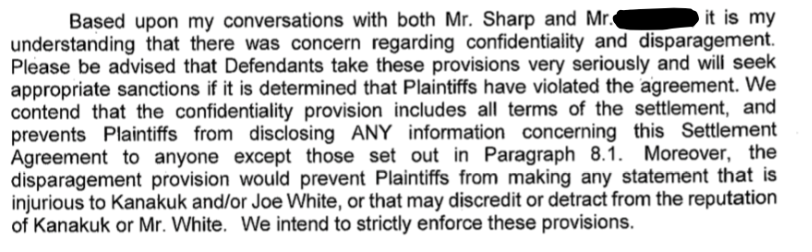

The parties could not, however, reach mutual agreement on the language of the clause. The victim and his family refused to sign the agreement Kanakuk proposed. Yet Kanakuk pressed on and tried to force the victim to sign anyway. It treated the “agreement to agree” as a final agreement and wrote a letter that contained the following threat:

When the victim and his family did not respond to the camp’s satisfaction, Kanakuk then filed two motions that not only sought to force the family to sign a non-disparagement clause, but also sought to sanction the victim’s family for speaking to the media and for failing to sign the agreement. The second sanctions motion sought more than $26,000 in attorneys’ fees as punishment for the family’s refusal to sign.

The judge dismissed the case and denied both of Kanakuk’s attempts to force the victim and his family to sign a non-disparagement agreement. The judge also denied the family’s attempt to force Kanakuk to sign a settlement agreement that omitted a non-disparagement clause. The parties were apparently left with an agreement to agree that never came to fruition. The victim’s family, through counsel, promptly informed the camp that “there is not a non-disparagement provision to which the parties have agreed.”

The fight over the non-disparagement agreement was no mere lawyer’s battle. The victim’s mother told us that Kanakuk “beat us down emotionally, mentally, and spiritually with intense pressure to sign the NDA.” The camp’s efforts, she said, “left us crippled by fear and pure exhaustion.”

In addition to neglecting the story above, Kanakuk’s response to our reporting about nondisclosure agreements misses a key point. Kanakuk can still pledge to maintain victim confidentiality while it releases the victims from their vows of silence. In other words, protect the victims’ privacy and let them speak if they want to speak. Some may choose to remain silent and keep that chapter of their lives closed. Some may want to break their silence. It should be their decision to make.

But that’s not the only defect in Kanakuk’s letter to its families. Here is one of its core contentions:

Unfortunately, several articles were recently published that misrepresent Kanakuk, its mission, and its reaction to events that transpired over a decade ago. I want to communicate with you in a transparent and forthright manner the truth about these claims. These articles would like you to believe that Kanakuk is not who we say we are. These articles believe they have the “facts.” They do not. The sad reality is their narrative is incomplete, inaccurate, and misleading. You can read our response here.

As you are probably aware—twelve years ago, one of our full-time staff members was convicted of abusing Kampers. Kamp is still devastated by this behavior and the damage caused. Any act of abuse is absolutely deplorable and stands counter to Kamp’s core mission and beliefs. This individual’s behavior sent shock waves throughout the Kamp community. It left an indelible mark and shook us to the core. It still hurts. But accusations that Kanakuk—or any of its leadership—knew of the abuse and covered it up are categorically false, misguided, and self-serving. At no time was anyone at Kanakuk charged with knowingly allowing abuse or failing to report suspected abuse.

The camp is moving the goalposts. We did not claim that Kanakuk “knew of the abuse” (the specific alleged crimes). We claimed that Kanakuk received multiple warnings that Newman had engaged in nude activities and other problematic behavior with campers. Kanakuk cannot contest this. Why? Because you can see the evidence yourself.

For example, here’s Joe White testifying that he knew about “nude four-wheeling” and chose not to fire Newman:

You don’t have to believe me that White knew about nude activities. Believe White, under oath.

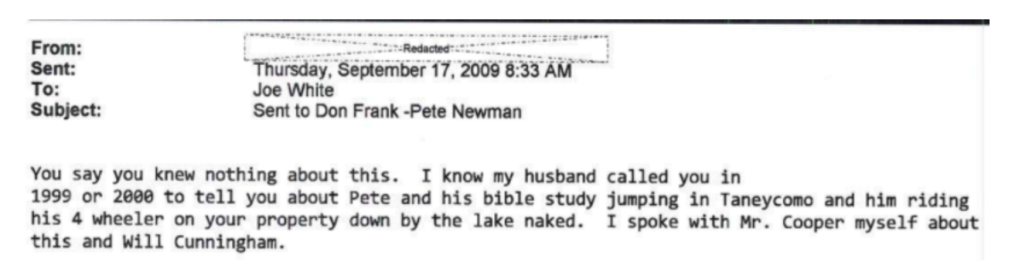

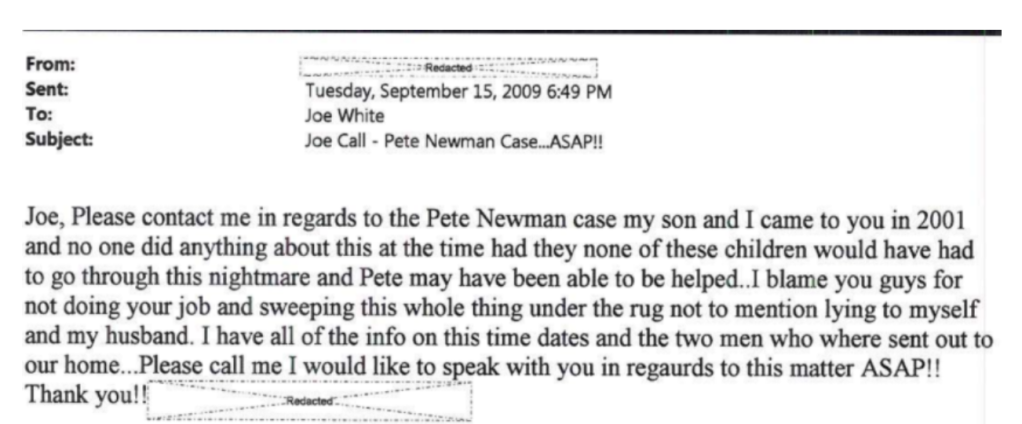

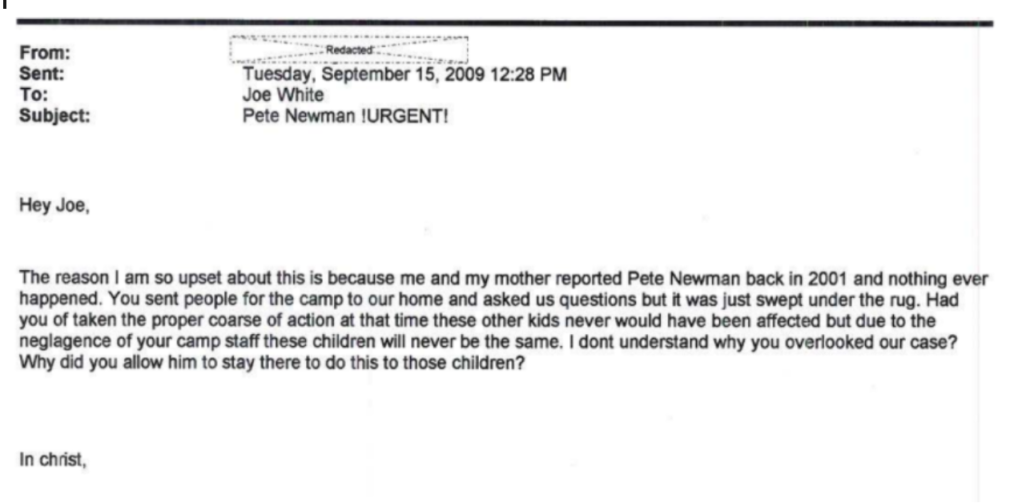

Similarly, here are images of anguished emails sent to White after Newman’s crimes were uncovered. Each email is from a person who says they told the camp of Newman’s inappropriate conduct, including nude conduct, up to a decade before Newman was fired:

And:

And:

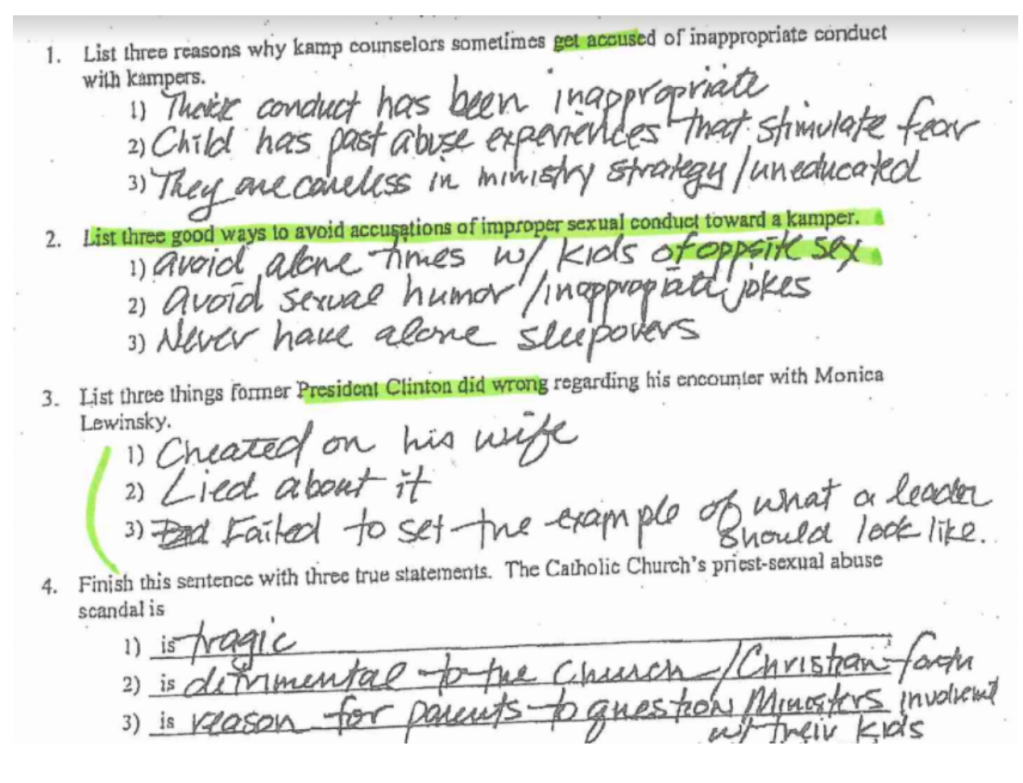

In addition, our report linked to a corrective action memorandum Newman’s supervisors wrote Newman in October 2003—roughly six years before his arrest. The memorandum began with a series of written questions to Newman and includes his handwritten answers. Here are the first four questions the camp asked, with Newman’s answers:

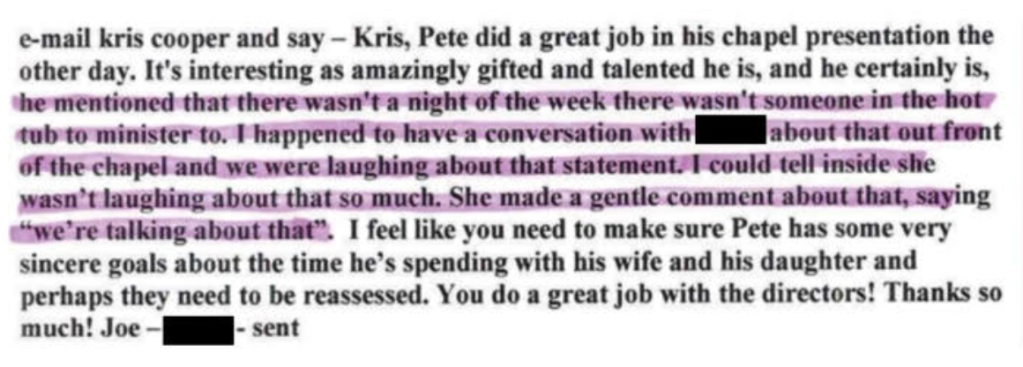

When you read those questions, isn’t it blindingly obvious that the camp was concerned about Newman’s sexual conduct? Also, look at this message from White to his secretary. It describes White as “laughing” that Newman said in a speech that “there wasn’t a night of the week there wasn’t someone in the hot tub to minister to.” This message was dated October 6, 2008, the year before Newman’s arrest.

This evidence clearly indicates that Kanakuk not only knew that Newman had engaged in inappropriate conduct, including nude conduct, it specifically identified concerns with sexual abuse in its communications with Newman.

Since Nancy and I published our report, a number of people have written and asked what Kanakuk (or any ministry) should do when sexual abuse occurs or when credible allegations of sexual abuse are made. At a minimum, the camp should release victims from their NDAs, commission an independent investigation of the event, release the results of the investigation publicly, and hold accountable those people inside the organization (including at the highest levels) whose negligence and/or recklessness failed the children in their care.

It is difficult to report on events that have long been shrouded in secrecy. We are happy to respond to specific allegations of inaccuracy and supplement the record with new evidence. But Kanakuk has not produced any evidence that our report is inaccurate, nor has it provided meaningful new evidence that alters the substance of our story. We invite you to read our original report, read the documents we link, and read Kanakuk’s full rejoinder. The facts speak for themselves.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.