I grew up during a scary time. My first political memories are of the Iran hostage crisis, sitting in long gas lines, and seeing glimpses of news reports about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. There was a palpable sense of American decline (the recession of 1981 and 1982 was brutal), and a deep fear that the escalating Cold War could grow hot, which would likely have meant mass death and the end of civilization as we knew it.

Moreover, social maladies plagued our land. Divorce rates were at an all-time high. Abortion and murder rates peaked.

If I had to peg the year of peak anxiety, it would be 1983. In September, a Soviet fighter shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, a passenger jet carrying 269 passengers and crew, including an American congressman. In November, ABC aired The Day After, a movie that depicted a sudden Soviet nuclear strike. Everyone watched it. I can still remember the hushed halls at school the next day.

Watch it now, and you can’t get past the 1980s special effects. But if you watched it then, it felt real. And what we didn’t know in November 1983 was that mere days before, during NATO’s Operation Able Archer ‘83, the Soviets had placed their nuclear forces on high alert.

I write these words not to diminish the challenges of the present moment at all. COVID is still taking lives every day. For the first time in generations, a great power has launched a land war in Europe. There’s an active risk of nuclear confrontation with Russia. And our nation is deeply, deeply divided.

At the same time, however, if I had to use a single word to describe my childhood, it would be “joyful.” Amidst profound geopolitical uncertainty and a degree of domestic social disorder that is far worse than we experience today, I grew up a happy kid. Because of my parents.

I grew up in a peaceful, intact, loving household. We enjoyed our time as a family. Some of my favorite memories in life are of playing basketball with my dad for hours, battling under the basket until late at night. I was grateful for that at the time, but there’s something else that I’ve only grown to more fully understand as I became a parent–in times of uncertainty, I first turned to my parents to understand how to react. I took many of my emotional cues from them.

If they were anxious, I was more anxious. If they were calm, I felt at peace. And when it came to the challenges of life, I can never remember a moment when they didn’t face the future with faith and hope.

I started with that bit of autobiography because of a story I read this week that not only sobered me on its own terms, it reflected the experience of many, many parents and friends. Our nation’s kids are facing a mental health crisis. The most recent top line statistics are here:

But don’t just believe the stats. Talk to parents of teens. Time and again, you’ll hear stories about deep anxiety, terrible depression, and crippling sadness. It’s one of those problems that everyone seems to know about, not just because it’s reported on the news but because every parent is either experiencing it with their own kids or knows parents who are.

As with virtually any complex social phenomenon, I reject monocausal explanations. I’m persuaded, for example, by voices such as Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge (and by kids’ own words) that social media is an important factor. I also believe that decreasing the stigma around mental illness has increased reporting about mental distress.

But I also wonder about something else–are kids taking emotional cues from their parents? Are we facing the future with faith and hope, or with animosity and anxiety? I was struck by an observation by a British theologian named Andrew Wilson. Visiting America, he sees pain.

And that pain is reflected in statistics that eerily mirror the statistics of rising childhood depression. For example, one year ago the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that between August 2020 and February 2021, the percentage of adults with recent symptoms of anxiety or a depressive disorder increased from 36.4% to 41.5%. Childhood suicide rates are high and increasing, but they’re still much lower than adults.

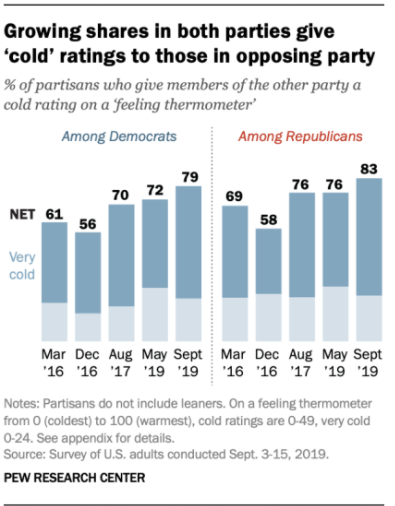

Adult anxiety, depression, and suicide are increasing just as adults are demonstrating increasing raw animosity against their fellow citizens. As the Pew Research Center has amply documented, partisan antipathy is growing “more intense” and “more personal.” The chart below, which documents how “cold” we feel for our political opposites, represents a spirit that is utterly contrary to a sense of national community and fellowship (much less a spirit of Christian love for our neighbors):

Compounding the challenge, educators and parents are frequently conscripting children into political causes, including by introducing them to activism at ever-younger ages. And how do they motivate kids? Often by using the same kinds of fear-based rhetoric that activates adults.

I also wonder if increased work from home can sometimes have an unexpected negative impact, even if eliminating a commute theoretically gives parents more time with their kids. Many millions of children now also live in their parents’ workplace, and they likely have greater direct exposure to the stress of their parents’ professional lives.

Now let’s add an additional ingredient–a cultural change in parenting styles that can negatively increase parental influence on our kids’ lives. We have new terms like “helicopter parenting” and “snowplow parenting” that indicate how parents both constantly hover over their kids and try–through influence and connections–to blaze an educational and career path for their kids.

In their indispensable book, The Coddling of the American Mind, Haidt and my longtime friend Greg Lukianoff have documented how a spirit of “safetyism” (which is rooted in adult anxieties) has deeply influenced how we raise our kids. On March 30, Peter Gray published an important piece in Psychology Today that addressed these same themes.

He argues that suffocating modern parenting prevents children from fulfilling three fundamental psychological needs, “autonomy, competence, and relatedness.” This paragraph is key:

I have long been concerned with the continuous rise, over roughly the past 50 years, in the rates of depression, anxiety, and suicides among children and teens. This increase in suffering has occurred during a period in which young people have been subjected to ever-increasing amounts of time being supervised, directed, and protected by adults—in school, in adult-run activities outside of school, and at home—and have experienced ever less opportunity to play freely and in other ways pursue their own interests and solve their own problems. I have argued that there is a cause-effect relation between these two historical trends (e.g, here and here). The pressure and continuous monitoring and judgments from adults, coupled with loss of freedom to follow their own interests and solve their own problems, results in anxiety, depression, and general dissatisfaction with life. (Emphasis added.)

It’s hard to overemphasize how contrary this “pressure and continuous monitoring” was to my childhood experience. My parents were strict, but they weren’t fearful. I enjoyed an immense amount of autonomy. Even as a young kid, I’d walk out of my house in the morning, stay out with friends (with rules about how far I could wander), return for dinner, then strike out again until curfew.

That is not a typical childhood experience today. And what do kids do when they’re “safely” at home or “safely” in the world of carefully monitored student and youth activities? They turn to their phone, which turns out to be not that safe at all.

Last week I had a wonderful visit to Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, where I gave a talk about political theology. I followed it up with a visit to Duke Divinity School where I addressed a similar subject. In both places I was asked the same question—what am I reading now that is helping me navigate both the intense anger and fury of online debate and the shocking realities of war, division, and disease?

I gave the most trite, stereotypically Evangelical answer ever: The Bible. But with a bit of a twist. I said that I was re-reading scripture but keeping a central fact in mind—every single syllable of the New Testament was written during a time of far worse disease, oppression, and danger. Life was far more contingent. Christian believers had no political power, and they worried about being killed, not canceled.

But despite that environment, the words of scripture are full of expressions of faith, hope, and love. They defy fear, quite explicitly. In 2 Timothy 1:7 the Apostle Paul declares, “For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but one of power, love, and sound judgment.” And he’s clearly not speaking of political power. Christians possessed none. Instead, believers are to have confidence in the power of a Savior who had just conquered death and hell.

Moreover, if we want to know what love is, Paul defined it elsewhere, in verses that have echoed in history:

Love is patient, love is kind. Love does not envy, is not boastful, is not arrogant, is not rude, is not self-seeking, is not irritable, and does not keep a record of wrongs. Love finds no joy in unrighteousness but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.

As for “sound judgment?” It speaks of sobriety and stability even in the face of overwhelming adversity.

These words are convicting for adults facing American politics. They’re convicting for parents raising American children. I don’t say this to indict any given parent or any given family. In many ways I’m speaking to myself. Even as I write, I’m asking myself if I’ve communicated the same degree of faith and hope that I heard from my own parents, and I know I’ve been found wanting.

Also, as all parents know, there is no formula for raising kids. Each of the statistics above refer to trends, not individuals. We’ve seen the best kids emerge from the most broken homes. We’ve also seen parents check every box of faith and love only to watch their kids struggle.

But we still know that we as a people—and we as parents—are prone to expressing greater anxiety and greater fear in the face of lesser threats and lesser dangers than generations of parents in the past, and it’s time to wonder if one of the reasons why our kids are anxious and in pain is that they’re reflecting and amplifying the anxiety and pain they see in their parents every day.

One more thing …

Fresh from answering burning questions like, “What the heck is an Evangelical?” or “What the heck is a Christian nationalist?” in this week’s Good Faith podcast, Curtis and I try to answer “What the heck is a fundamentalist?”

Why focus on fundamentalism? As I’ve written before, I think any analysis on Evangelical divides that’s framed as conservative versus moderate or woke versus anti-woke is missing the real distinction. There simply aren’t that many Evangelical moderates, and there certainly aren’t that many woke Evangelicals. But there is a big divide between Evangelical and fundamentalist temperaments and attitudes, and that divide manifests itself in multiple material ways.

Give the podcast a listen, and please let us know your thoughts.

One last thing …

Of all the songs I’ve shared, this remains my favorite, and it’s one I go back to whenever I think of our nation’s immense challenge with despair. It includes not just an assurance of God’s love and our worth but also a searing moving moment of poetry in the middle. Even if you’ve listened before, you’ll want to listen again:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.