In two days we’ll face the one-month anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s been a shocking month. It’s said that no plan survives first contact with the enemy. It can also be said that few predictions survive the first weeks of war.

The Russian military, modernized and victorious in multiple smaller-scale conflicts since the Second Chechen War is facing a bloody stalemate, and the best available reports indicate that its equipment losses are so catastrophic that it might take years to rebuild its force.

The West—allegedly divided, demoralized, and wasting away in its self-absorption and decadence—has united so completely and decisively that even foreign policy hawks are struggling to restrain millions of citizens who are calling for no fly zones or other dangerous escalations to save Ukraine from Russia.

Volodymyr Zelensky was an outmatched former comedian who once danced in a music video in high heels and leather pants. Vladimir Putin was the bare-chested manly man who made Russia (and Russian Christianity) great again. Yet now Zelensky is a world leader of towering moral stature, and Putin is outmatched, reeling from battlefield setbacks and struggling to save his standing at home and abroad.

We’re not just shocked by the course of the war so far but also by its incredible intensity. It’s been generations since two advanced militaries went to war with each other, and the sheer lethality of the war is staggering to behold. Cities are in ruins, and men are fighting and dying at rates that are difficult to comprehend.

After this first week of the war, I tried to answer some common questions about the conflict, including how and why Putin miscalculated and whether Ukraine can actually win. I’ve revised some of my thoughts since, and new issues are arising. So let’s start with a new FAQ that reflects the questions I’m getting every day.

What’s the overall state of the war so far?

Let me give a new meaning to a word you already know, “culminate.” If you’ve listened carefully to military experts analyzing the course of the war so far, you might have heard several say that the Russian advance has “culminated” outside Kyiv or that it’s “culminating” in the east. Or perhaps that it’s about to culminate in the south.

In a military sense, when an offensive culminates, it essentially has reached the point where it has achieved all it can achieve. It’s gone as far as it can go. In military jargon, the term means, “the point at which continuing the attack is no longer possible and the force must consider reverting to a defensive posture or attempting an operational pause.” Sometimes offensives culminate because they outrace their supply lines. Sometimes they culminate because they’re defeated in battle or because of simple exhaustion.

The best available evidence indicates that Russia’s initial attacks have largely culminated. They’ve gained ground over the past month, but they can’t gain much more, at least for now. Troops are exhausted, units are decimated, and equipment losses are catastrophic. Even the toughest soldiers are still human, and people can fight for only so long, even if they’re winning, and it’s been clear for some time that Russia has failed to achieve its goals.

Russia’s advance has largely stalled. It’s besieging Mariupol (and the city may fall), but Ukrainians are refusing surrender demands. Kyiv still isn’t encircled. Ukraine took Russia’s first and (for now) biggest punch, and it not only survived, it’s punching back. Hard.

Wait. Does this mean Ukraine can actually win?

From the beginning, the short answer to that question was “yes,” but it was a tentative yes, the kind of thing you say to note that anything is possible. I called Ukrainian victory “possible, but unlikely.” Writing in The Atlantic, I predicted that Russia would respond to its early missteps by adopting more classically Russian tactics and deploy overwhelming, indiscriminate firepower.

It has done exactly that, yet its advances are still largely stalled. Local Ukrainian counterattacks are retaking some lost ground, and now the Pentagon estimates that Russian combat forces in Ukraine have shrunk “below 90 percent of the original force.” Former Bush administration State Department counselor Eliot Cohen has argued that it’s time to say Ukraine is winning the war:

The evidence that Ukraine is winning this war is abundant, if one only looks closely at the available data. The absence of Russian progress on the front lines is just half the picture, obscured though it is by maps showing big red blobs, which reflect not what the Russians control but the areas through which they have driven. The failure of almost all of Russia’s airborne assaults, its inability to destroy the Ukrainian air force and air-defense system, and the weeks-long paralysis of the 40-mile supply column north of Kyiv are suggestive. Russian losses are staggering—between 7,000 and 14,000 soldiers dead, depending on your source, which implies (using a low-end rule of thumb about the ratios of such things) a minimum of nearly 30,000 taken off the battlefield by wounds, capture, or disappearance. Such a total would represent at least 15 percent of the entire invading force, enough to render most units combat ineffective. And there is no reason to think that the rate of loss is abating—in fact, Western intelligence agencies are briefing unsustainable Russian casualty rates of a thousand a day.

Cohen makes a convincing case, and he notes that it’s not as if Russia has been holding back. It’s committed most of its ground combat power, and even if it mobilizes its reserves, they’re poorly trained, and their equipment is second-rate. Ukraine, by contrast, is receiving a flood of advanced weaponry. So long as it stays in the fight, it won’t lack equipment, and given the total mobilization of the nation for war, it won’t lack men.

What can Russia do to turn the tide?

As the Institute for the Study of War has observed, “The doctrinally sound Russian response to this situation would be to end this campaign, accept a possibly lengthy operational pause, develop the plan for a new campaign, build up resources for that new campaign, and launch it when the resources and other conditions are ready.”

This is a normal pattern in extended European wars. Dueling combatants launch competing offensives, each typically designed to last for a limited period of time to achieve a defined objective. We’re seeing that pattern just a bit already, where Ukraine is launching its own limited offensives to take advantage of weaknesses in Russia’s positions.

That’s a long way of saying that Putin may well decide that losing simply isn’t an option, that he’ll engage in “standard” great power tactics, reinforce his army, and launch a series of limited offensives that are designed, over time, to grind Ukraine to dust.

But given the severity of Western sanctions and the difficulty in replacing trained troops and advanced equipment, that option might not be reasonably available. So he might cut his losses in ground forces and try to force concessions from Ukraine by using his advantage in artillery and air power to pound Ukrainian civilian and military infrastructure from a distance, to attempt to essentially bomb the Ukrainians into compliance.

At the same time, while we focused a great deal on Russian losses and Russian failures, we don’t have great visibility on Ukrainian losses (as of two weeks ago, the Pentagon estimated the Ukrainian military could have suffered as many as 4,000 soldiers killed in action). Ukrainian morale appears high, and they’re fighting with remarkable tenacity and effectiveness, but they’re just as human as the Russian soldiers, and both armies are susceptible to reaching breaking points.

Putin still has cards to play, he still holds Ukrainian territory, and he still possesses an overwhelming advantage in raw firepower. I now think it’s highly unlikely that he can conquer Ukraine outright, but it’s an open question whether he can inflict so much damage on Ukraine that he can snatch a degree of victory from the jaws of his early humiliating defeat.

What’s worrying you the most?

The first answer—just because of the potential immense cost in human lives—is dramatic Russian escalation, including the potential use of tactical nuclear weapons to force a favorable settlement of the war. The probability is low (unless NATO intervenes, then the chances of a nuclear exchange rise dramatically), but the potential cost is so high that we have to keep it front of mind.

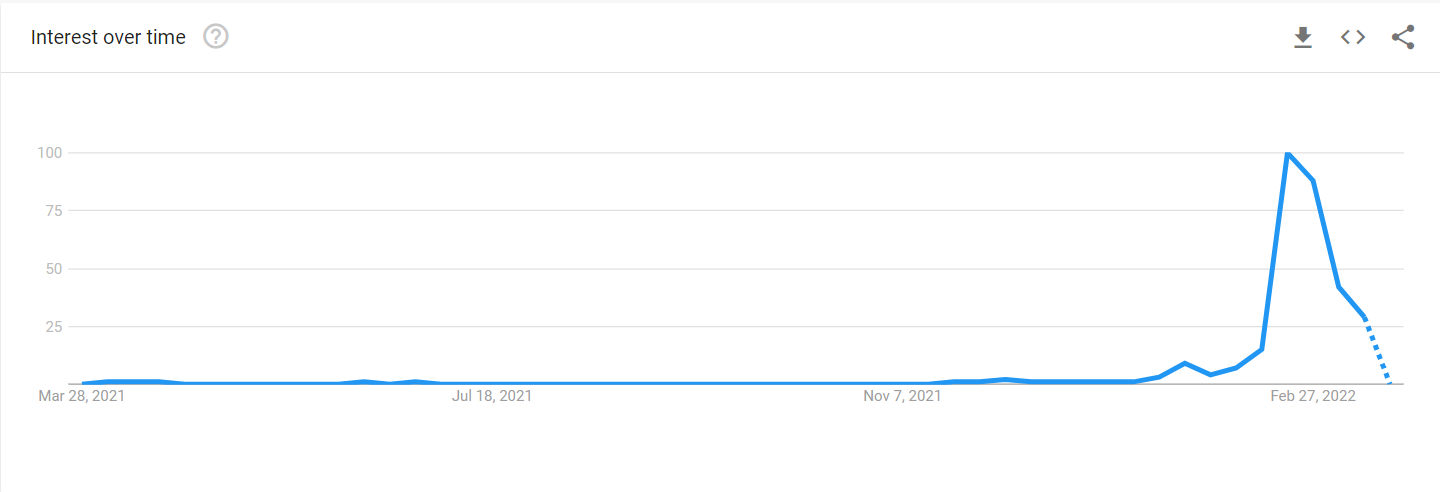

But there’s something else that’s high probability that also has a high potential cost over time—Western indifference. Look at this chart from Google Trends, representing interest over time in the search term “Ukraine”:

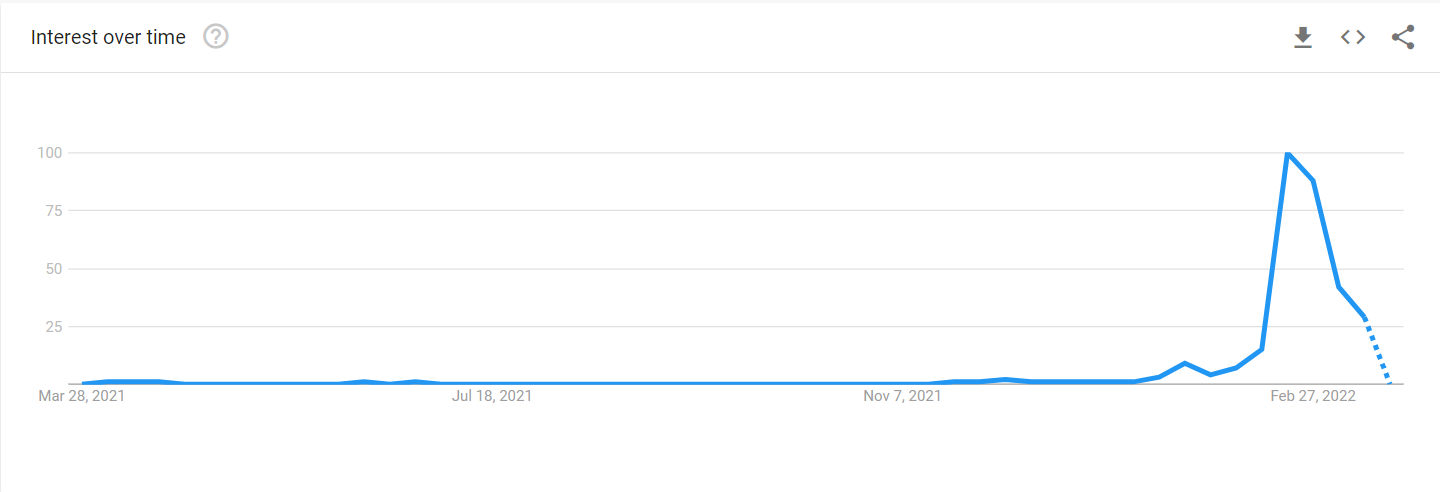

And here’s the chart for “Russian invasion”:

What is the true staying power of Western interest in the crisis in Ukraine? We obviously can’t expect people to maintain the same level of interest once the initial shock of the invasion wears off. Heck, public interest in American wars wanes quickly until there are dramatic new developments.

But disinterest helps Putin. Disinterest can destroy urgency. It facilitates a war of attrition, where the daily toll in destroyed hospitals, theaters, and apartment buildings fades to the background of American (and world) awareness.

By the Trump administration Americans were so war-weary that they barely paid attention to the Battle of Mosul, one of the largest urban battles in the last half-century. And Americans were directly engaged in that fight, day after day and week after week.

Let me end on an optimistic note. While I’m worried about indifference, I’m hopeful that enough Americans will stay engaged that American policy and American resolve won’t waver. It also seems that American attitudes about the war are largely set. The vast majority understand that Russia is the aggressor and support Ukraine. And while Republicans are more likely to be neutral in the conflict than Democrats, Ukrainians enjoy majority support from every political faction—Democratic, Republican, or independent. All of the momentum is for Ukraine. There is no real public momentum for Russia. And even if interest fades, the fundamental reality should remain. Americans stand with the nation that’s fighting Putin’s imperial regime.

One more thing …

Sadly we couldn’t record an Advisory Opinions podcast on Monday or today—Sarah is sick with COVID (she’s doing well and calls it a “thank goodness for the vaccine” level of illness)—so we couldn’t spend time evaluating Sen. Josh Hawley’s alarming claim that Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson has “a pattern of letting child porn offenders off the hook for their appalling crimes, both as a judge and as a policymaker.”

Fortunately, my friend and former National Review colleague Andy McCarthy has done the homework and reached the same conclusion I did—Hawley’s claim is a smear. I’d urge you to read Andy’s two pieces. In the first, he discusses Judge Jackson’s position on mandatory minimum sentences for the receipt and distribution of pornographic images. In the second, he discusses Judge Jackson’s actual sentencing decisions, and how they’re in line with government recommendations.

Here’s his conclusion:

[T]he cases Senator Hawley cites do not show that Judge Jackson is an unusually soft sentencer in child-porn cases, much less that she is indulgent of “sex offenders” who “prey on children.” She is certainly not a harsh sentencer. The terms she has meted out, though, are compliant with the law and usually equal or exceed the sentencing recommendations of the court’s probation department. Moreover, the fact that the Justice Department’s own sentencing recommendations are sometimes dramatically lower than the guidelines range underscores that the guidelines in child-pornography cases — at least as applied to low-level, nonviolent offenders whose crimes entail consumption rather than production of pornography — are extraordinarily harsh. That is why they have drawn criticism from judges and practitioners across the political spectrum.

I disagree with Judge Jackson’s judicial philosophy, and I believe it’s completely acceptable to oppose her nomination on that basis, but Hawley’s claims cross the line. They’re a disingenuous misrepresentation of her record, and conservatives should not believe or share Hawley’s smear.

One last thing …

There is a remarkable amount of drone footage of the combat in Ukraine. I’m sharing a bit below (it’s not graphic, but it’s very real and can be disturbing) to show why the combat in Ukraine has been so lethal. Ukraine’s Western-supplied anti-tank weapons are remarkably effective, but the courage it takes to approach so close to a Russian tank column is breathtaking. Encounters like this are happening across Ukraine:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.