Hi,

Let’s start with some history.

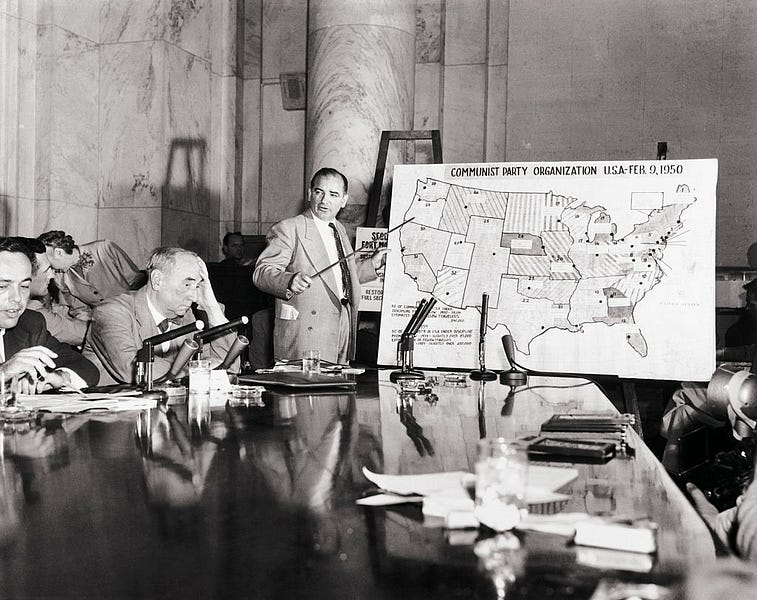

It was on this day in 1954 that Army lawyer Joseph Welch asked Sen. Joseph McCarthy, “Have you left no sense of decency, sir, at long last?”

The moral of the story—recounted by TV pundits, high school civics teachers, and Hollywood scriptwriters—is that shame and decency prevailed when one brave man spoke truth to power.

I don’t really object to that moral. To paraphrase James Cromwell in Babe, “That’ll do, pundit. That’ll do.”

But the truth of the story is a bit more complicated. Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s legal henchman, negotiated a deal with Welch before the hearings. If Welch refused to make an issue of Cohn’s avoidance of the draft, then McCarthy would not make an issue of a junior associate of Welch’s, Frederick G. Fisher Jr., who had once been a member of a communist front group called the National Lawyers Guild.

But McCarthy lost his temper during the hearing, because Welch—a savvy courtroom operator—had grilled Cohn too aggressively. “Infuriated when Welch was baiting Cohn during a cross-examination, McCarthy mentioned the attorney and his affiliation,” writes Harvey Klehr, “ignoring Cohn’s frantic efforts to stop him.”

That was the context for Welch’s rhetorical knifing. “Senator, may we not drop this?” Welch asked. “Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator; you’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?”

McCarthy kept ranting. “Mr. McCarthy,” Welch calmly replied when the gin-soaked senator finished. “I will not discuss this further with you. … If there is a God in heaven, it will do neither you nor your cause any good.”

“The room erupted in applause,” Menand writes. “Even reporters applauded. It was June 9, 1954, the thirtieth day of the Army-McCarthy hearings. The dragon had been slain.”

It was all a set-up. In the words of Louis Menand:

What had actually happened is that the bamboozler was bamboozled. It was not McCarthy who had outed Fred Fisher. It was Joseph Welch. The whole Fisher story had appeared two months before in a front-page article in the Times. “Mr. Welch today confirmed news reports,” the Times said, “that he had relieved from duty his original second assistant, Frederick G. Fisher, Jr., of his own Boston law office because of admitted membership in the National Lawyers Guild, which has been listed by Herbert Brownell, Jr., the Attorney General, as a Communist-front organization.” The article was accompanied by a photograph of Fisher. Welch’s lament that McCarthy had ruined Fisher’s reputation was bogus. Fred Fisher was a trap, and McCarthy walked right into it. It has been said that when Welch left the hearing room, with tears in his eyes, he winked at a reporter he knew. I doubt he did this, but he was certainly entitled to.

Again, I don’t think any of this erases the top line moral of the story. But it’s worth remembering nonetheless. History is almost always more complicated than the popular narratives it produces.

Conspiracy of conspirators.

But let’s move on to another lesson. I’m going to invoke author’s privilege and get to it in a roundabout way.

Contrary to the opinions of some left-wing diehards, communism really was a serious domestic threat to the United States. There were communist cells in the United States. The Rosenbergs did steal nuclear secrets. Alger Hiss was a communist. I won’t wade into the debate on whether the National Lawyers Guild was a communist front group, but one has to concede that it was a prominent nest of communists.

Henry Wallace, FDR’s penultimate vice president (and former editor of The New Republic) probably wasn’t a communist himself, but his picture certainly should be in the dictionary next to “useful idiot,” a term attributed to Lenin to describe Western intellectuals who dutifully carried water for the communist cause. Wallace had a gift for surrounding himself with Soviet spies and fellow travelers. Hiss worked for him at the Department of Agriculture. And Wallace wanted to make Harry Dexter White—later confirmed as a Soviet informant in the Venona papers—secretary of the treasury. Toward the end of World War II, Wallace met with the Washington head of the NKVD (essentially the Soviet police), and offered him access to American nuclear scientists.

Wallace ran for president in 1948 as the nominee for the Progressive Party, which was essentially a giant communist front group. No less than I.F. Stone—hardly a rabid anti-communist—wrote in 1950: “The Communists have been the dominant influence in the Progressive Party . . . If it had not been for the Communists, there would have been no Progressive Party.”

John Abt, the party’s chief lawyer, was a member of Hiss’ cell. Lee Pressman, who headed the platform committee, was a communist. Wallace’s speechwriter, Charles Kramer, was exposed by the Venona papers as an active Soviet spy. Even Rexford Tugwell—arguably the most left-wing member of FDR’s Brain Trust—eventually felt the need to leave the Progressive Party because it was simply a communist front.

Forgive the long digression into my Big Box of Anti-Communist Receipts. I bring it up for two reasons. First, today is the 16th anniversary of my dad’s passing and I know it would make him smile to see me carrying the torch of his anti-communism.

Second, my actual point: Conspiracies invite conspiracy theories, which in turn invite real conspiracies, which in turn beget even crazier conspiracy theories. It’s a chicken-or-the-egg dynamic, so it’s not worth playing “Who started it?” games. Anti-communism in America was indeed shot through with paranoid, witch-hunting hysteria. But if we’re going to use the term witch hunt seriously, one must also concede that there were also plenty of actual witches. We can debate how dangerous they were or how necessary or unnecessary the effort to deal with them was, but no informed and reasonable person can dispute that the various narratives spawned by that period had at least some facts on their respective side.

Communists were involved in various conspiracies. Anti-communists recognized this fact and sometimes got carried away, embracing ever more grandiose theories that got away from the facts. Ike wasn’t a communist, he was a golfer. Fluoride wasn’t an effort to dilute our precious bodily fluids. Communists in turn behaved in ever more conspiratorial ways because they were reasonably afraid of persecution—or prosecution. They invented their own crazy conspiracies. (They were aided in this by the Soviets, who spent a great deal of effort seeding the West and the Third World with propaganda.)

I got to thinking about this in part because I’ve been reading up on the French Revolution (inspired by the excellent Revolutions podcast). The unfolding revolution was driven mad by rolling conspiracy theories because the revolution was shot through with competing conspiracies. Robespierre killed Danton in part, he believed, to prevent a conspiracy against him. Many surviving Danton loyalists then mounted a conspiracy against Robespierre—which was a reasonable thing to do given that they rightly assumed they’d be next. Conspiracy theory begat conspiracy theory, which begat ever more conspiracy theories.

The other reason I’ve been noodling over this is that I think a similar dynamic is bedeviling our politics. I’ve been having a running disagreement with Joshua Tait over the right’s alleged “anti-democratic” nature. He thinks there’s a powerful strain of anti-democratic sentiment in intellectual conservatism. I disagree. I think we’re witnessing competing elite, partisan, and populist moral panics over democracy. This has been building for a long time (see Jim Geraghty’s excellent piece today) but it’s clearly intensifying now.

As if to lend me aid and comfort in this disagreement, Morning Consult has a new poll out today. It finds that 77 percent of voters believe America’s democracy is currently being threatened. But here’s the key part: More Republicans (82 percent) say this than Democrats (77 percent).

Democrats have convinced themselves—not always without reason—that Republicans are conspiring to subvert democracy. Republicans—not always without reason—have convinced themselves that Democrats are conspiring to subvert democracy.

I’m not going to score the competing claims here. My point is that fear of the other side cheating creates, almost in dialectical fashion, overreactions to prevent it. These overreactions, in turn, are all the proof the other side needs to confirm their fear that it’s the other side declaring war on democracy. And on it goes.

Yes, there’s a healthy portion of both-sides-ism to my point. But that doesn’t mean it’s not true, nor does it imply there’s a perfect symmetry to each side’s transgressions. My views on Trump’s effort to steal the 2020 election are well known. The lack of symmetry, in fact, is the point. It’s a “Chicago way” dynamic. Remember: The line isn’t, “If he pulls a knife, you pull a knife of equal size.” It’s, “If he pulls a knife, you pull a gun.”

Each side thinks they’re just responding in kind, when in fact they’re escalating (or, at least, the response is seen as an escalation). This dynamic isn’t confined to debates about election practices. One of the reasons the culture war has been intensifying for 30 years is that each side has convinced itself it always loses.

Pandemic politics have been like the Spanish Civil War—a proxy battle for the larger conflict. Masks for everyone! Masks for no one! Vaccine passports for everything! Vaccine passports for nothing! Both positions are soul-achingly idiotic.

I think Ross Douthat offers some good arguments here against some sort of democratic Gotterdammerung in 2024. And he may be right. But if there’s been one lesson to be learned from the last five years, it’s that the loudest few often have more sway than the quiet many. I’d like to think we’ve seen the worst of it. I’m just not sure I’m willing to bet that way.

Various & Sundry

My daughter is graduating from high school on Friday. If I can get the Friday G-File (and Friday Ruminant) done between now and then, I will. Otherwise I’ll see you next week (“No you won’t, this is a ‘news’letter”—The Couch) after I spend the weekend sobbing to the tune of “Cats in the Cradle.”

Also, I don’t usually promote the Remnant podcast too aggressively in this space, but a lot of listeners have told me the last few have been the best I’ve ever done. I can’t really judge that. But I can say I learned from and enjoyed my conversations with Shawn Bushway of RAND and Jonathan Rauch of—shudder—Brookings a ton.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.