Hi,

I’m sorry to report that I’ve been felled by a nasty malady (of the non-COVID variety). I didn’t want to bail on today’s newsletter, but I also don’t feel well enough to churn out something that would be worth your valuable time. So instead I’m publishing an excerpt from my underrated second book, The Tyranny of Cliches. While it came out a few years ago, much of it is relevant today, including my chapter on the middle class and the cognitive dissonance of the American left. This is a trimmed down version. I hope to be recovered enough for the Friday G-File. If I’m not, I’ve got bigger problems.

So say the Asian, the Hispanic, the Jew,

The African and Native American, the Sioux,

The Catholic, the Muslim, the French, the Greek,

The Irish, the Rabbi, the Priest, the Sheikh,

The Gay, the Straight, the Preacher,

The privileged, the homeless, the Teacher.

—Maya Angelou, “On the Pulse of Morning”

What do all of these folks say? I’m not too sure. But you can figure that out for yourself if you want to by reading Maya Angelou’s “Inaugural Poem,” delivered at Bill Clinton’s swearing-in as the 42nd president of the United States. This passage serves as a less than ideal example of the left’s obsession with identity politics—the idea that we are all locked into our status as gay, straight, black, white, etc. But there are three reasons why I’ve chosen it. First, it’s notable that at the inauguration of a president of the United States, the poem listed just about every flavor of humanity ever captured in a Benetton ad, but never once mentioned Americans. Second, it highlights the intense cognitive dissonance of the American lleft.

And third: It rhymes, which is nice.

Let’s circle back to number two. Bill Clinton won the Oval Office in large part because he refused to fall into the same trap as so many Democrats before him. Namely, the Democratic Party had become (and largely remains) the tail on the dog of special interests, particularly labor unions, racial grievance peddlers, feminists, limousine liberals, and the rest of the usual suspects. He cast himself as a different kind of Democrat, who wanted to “end welfare as we know it” and offer a “hand up not a hand out.” He attacked the brilliantly self-parodying rapper Sister Souljah, distanced himself from Jesse Jackson Jr., and, most importantly, talked relentlessly about the “middle class.”

Hence, the cognitive dissonance. You see, Bill Clinton and his advisers mastered the art of using the term “middle class” to win elections for a party that is obsessed with categorizing people in terms that negate the very idea of a middle class. Moreover, once elected, and all in the name of “protecting” the middle class, they put in place programs and championed ideas that undermined the stability of the middle class.

“Middle class” is a confounding term. Everyone uses it. Everyone claims to know what it means and who it describes, and yet it is almost entirely useless as a term of economic precision and deeply misleading as a term of political identity. In 2008, both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama ran for president with policies predicated on the assumption that 98 percent of Americans were, in effect, middle class. It tells you something that a party widely associated with its concern for the poor talks about the middle class far, far more.

That’s not to say Democratic politicians don’t care about the poor. I’m sure they do. But they also understand that even the poor—at least the voting poor—tend to think of themselves as the middle class, or aspire to be members of it. So when they talk about the middle class versus the rich, what they in fact mean is everybody versus the rich. In other words, being for the middle class, at least in many contexts, is just code for being against the rich. This has profound and pernicious public policy implications (to which we’ll return).

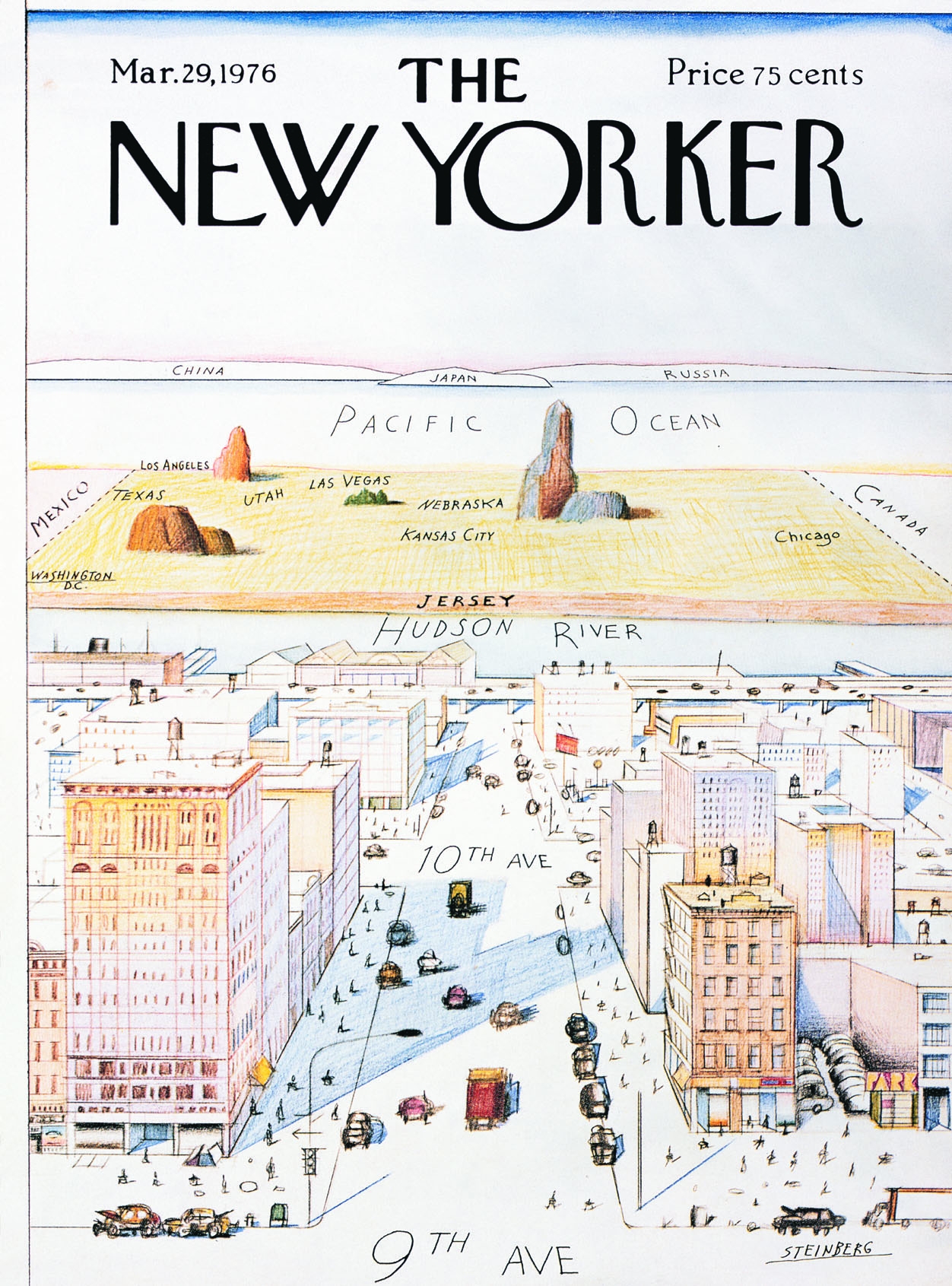

But there’s another meaning to the middle class: “Middle America,” traditional America, flyover America, Main Street, Norman Rockwell America. It means the America of old-fashioned values and norms, the part of the map that got edited down to next to nothing in that famous New Yorker cover depicting the Manhattanite’s view of America from Ninth Avenue. Democrats can never—ever—be caught appealing to what the hard campus left calls “white America,” because white America is the very thing that the campus left sees as the author of all of our problems and the primary target of all progressive reforms. That’s why the term “middle class” comes in so handy. It is a way of appealing to the heartland in terms that cannot be effectively faulted by the gargoyles on the parapets of the ivory tower.

This is not to say that the gargoyles don’t look down upon the middle class. Despising the traditional-minded, religious, hard working middle class—once known to elite, effete, intellectual types as the “bourgeoisie”—has been the great and abiding pastime of the very same elite and effete intellectual types for centuries. Stendhal said that small businessmen made him want to “weep and vomit at the same time.” Hatred of the bourgeoisie is “the beginning of all virtue,” proclaimed Gustave Flaubert. I learned from David Brooks that Flaubert even sign his letters “Bourgeoisophobus” to signal just how much he despised “stupid grocers and their ilk.”

At first, America was not a hospitable climate for bourgeoisophobia. The Founders were split not on the question of whether the bourgeoisie was good or bad, but which bourgeoisie to love the most. The Hamiltonians had a vision for America as a “commercial republic.” The Jeffersonians had a vision of America as a democracy of self-sustaining yeoman farmers. It took generations of wealth accumulation for America to produce an entire class of intellectuals who could hate the middle class country that produced them.

In the early 1920s, American liberals turned their backs on the country that sought a “return to normalcy.” Disgusted with the triumph of the “Babbitts,”—the pejorative label for middle class philistines, taken from the main character of Sinclair Lewis’ novel of the same name—a slew of articles and books appeared denigrating “middle America” as dimwitted, backward, and irredeemably provincial. The Nation ran a whole series of articles under the heading “In These United States” purporting to reveal that Manhattan was an island of sophistication in a vast wasteland of American backwardness. Perhaps not surprisingly, the South was an object of particular scorn. One writer believed that Mississippi could only be saved by an invasion of civilizing, cultured missionaries from the North. Another scratched his head to ask what, if anything, Alabama had ever contributed to humanity.

The Midwest and West were hardly spared either. The story of Colorado was a tale of “continuous colossal waste.” The famed Kansan progressive William Allen White lashed out that his state’s own culture of self-improvement was now backward, too: “No great poet, no great painter, no great musician, no great writer or philosopher” could be found in the Sunflower State. Meanwhile, the Ohio-born novelist Sherwood Anderson asked: “Have you a city that smells worse than Akron, that is a worse junk-heap of ugliness than Youngstown, that is more smugly self-satisfied than Cleveland?”

There is certainly some significance to the fact that so many of these writers were condemning their own communities and home states. In a sense, progressivism nurtures and is nurtured by a tendency to loathe what is near and love what is far. Those who escape the provincial must justify their own betrayal of their roots. The same story, but on a generational scale, played itself out to some extent in the 1960s when the new left’s chief complaint (before they latched on to the civil right’s movement) was how good they had it. Comfort, it seemed, was a sin. The opening line from the Students for a Democratic Society’s 1962 Port Huron Statement says it all: “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.” In The Feminine Mystique, founding mother of modern feminism Betty Friedan indicted the traditional middle class home as “a comfortable concentration camp” where women were held captive.

This line of thinking also helps demonstrate that the second wave of feminism was in no small part launched as a Trojan Horse for an older and more familiar Marxist assault. It may have evolved into something different and more mainstream, but the DNA is there. And since we’re on the subject of Marxism, we might as well deal with it here since anyone venturing into the realm of class must at some point pull over at Karl’s Funland and throw some darts at the balloons, squirt water in the clown’s mouth, and tease the dancing monkeys.

According to most conventional discussions of Marxist theory, there are only two classes: the workers and the owners, or the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. “By bourgeoisie,” explains Marx in The Communist Manifesto, “is meant the class of modern Capitalists, owners of the means of social production and employers of wage-labor.” The proletariat, meanwhile, are “the class of modern wage-laborers who, having no means of production of their own, are reduced to selling their labor-power in order to live.”

The problem even for Marx, never mind his intellectual heirs, is that whenever one actually looks at people as they actually live, it turns out that there are a lot more classes than just two. That’s why Marx is, to borrow a term from social science, such a hot steaming mess. In Das Kapital he writes that there are in fact three classes: The capitalists, proletarians, and the landowners. But then pretty soon Marx had to add the petty bourgeois and the peasants to his list of classes. That makes five. No wait, it’s six, actually, because he divided the peasants into two types: The lowly serfs and the land-owning peasants.

Then there are the “ideological classes”—who are sometimes the handmaidens of the capitalists and sometimes their own class, it depends apparently on which side of the bed Marx got up from that day. Sometimes he talks about the “ruling classes.” In Britain they are the “aristocracy,” “the moneyocracy,” or “finance aristocracy” and the “millocracy.” There’s also the “lower middle class,” which draws its members from the ranks of the petty bourgeoisie, depending on what they do, what they make, or how much they earn. Then, of course, there’s the “lumpenproletariat,” my favorite of the umpteen classes found in Marx’s allegedly two-class system. The Communist Manifesto defines them as the “the dangerous class, the social scum, that passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of old society.” (Think of them like the henchmen Hedley Lamar wanted to enlist to his cause in Blazing Saddles.)

The reason Marx’s analysis suffered from such an incontinent stream of classes is that humanity is simply not easily, reliably, or sufficiently categorized by class. In his myopic arrogance, Marx insisted on imposing a single mode of analysis on humanity. It would be like dividing the entire world into those who are left-handed and right-handed. Yes, you would learn and highlight some very interesting things about the differences and interactions of southpaws and decent humans (I don’t trust left-handed people!), but that would hardly unlock the mysteries to every realm of life. To look upon the interactions of the priest and the confessor, mother and child, doctor and patient, soldiers and their comrades, musicians and their audiences as exclusively, or even primarily, economic transactions is to cram the square pegs of your ideology into the round holes of reality.

Europeans—and later Asians—found Marxism particularly plausible because class was always a more salient concept on the continent. But Marx mistook cultural arrangements for “scientific” categories. In the United States, class played—and continues to play—far less of a role. For most of the 19th century, the average American was an owner— or co-owner with his family—of his own means of production. Prior to the Civil War, only a fifth of the population lived in cities, and most people lived on their own farms. With the advent of urbanization and industrialization, the working classes—i.e., the proletariat—grew quickly. They also rapidly carved out a lifestyle that made them if not fully bourgeois (whatever that actually means), then certainly prosperous enough not to feel exploited. Moreover, the working classes saw literally millions of their children enter the upper classes simply by stint of their hard work. The notion that class was an iron cage locking people into a permanent struggle with the ruling classes simply never caught on.

To be sure, class is not an exclusively Marxist term, even if all discussions of class have an oily Marxist residue to them akin to the greasy film on the tables at a Chuck-e-Cheese. Marx’s great rival in academic debates about class was Max Weber, who defined class not so much in terms of income, but social authority. Weber’s vastly superior analysis held that a given society’s organization of classes was contingent on a specific culture, and that income had far less to do with the rankings than the Marxists thought. In America, the so-called new class of professors, journalists, education bureaucrats, social workers, and activists make far less money than the typical orthodontist but have far, far more influence over our culture. Perhaps this is one reason why the term rich is routinely defined in the fine print of Democratic proposals as income just slightly above what the more successful workers in these fields make.

Bill Clinton was a quintessential member of this new class (and you thought I forgot about him). A man never much interested in making money (until he left the Oval Office), he was from his teen years onward fixated on politics. His political success lay in brilliantly updating the Nixonian formula of treating the vast, mostly white American middle class as an identity politics group without ever conceding that was what he was doing. Nixon appealed to the “silent majority” of middle America, which political scientist Richard Scammon famously defined as “unyoung, unpoor, unblack,” and he won reelection in a landslide.

Twenty years later, Bill Clinton marketed his 1992 campaign around the theme of “Fighting for the Forgotten Middle Class.” The brilliant trick, however, was that by 1992, according to Clinton’s pollster Stan Greenberg, 90 percent of Americans considered themselves to be “middle class.” In other words, it was a term that seemed to be about “class” but was in reality about everything except class. It was an appeal to classically bourgeois values masquerading as class warfare. The background issues in 1992 were as much crime, welfare, race riots, and cultural rot as they were the “economy stupid.” But a Democrat couldn’t talk about those issues directly, at least not without offending his base or the white middle class voters he needed to win. Middle class anxieties were, are, and always have been about more than mere economic concerns. Clinton’s populist appeal to the middle class was a dog-whistle signal to white voters telling them, in effect, “I get it.” He wasn’t subtle about it.

American affluence has always been a vexing challenge for liberalism. Just as the hard left loathed the bourgeois’ “comfort,” mainstream liberalism despises their complacency. In the 1950s, old-style mainstream liberalism had overseen a massive explosion in American prosperity after World War II, thanks to both good fortune and effective policies. But at a certain point, it seemed liberalism may have run its course. In 1957, Arthur Schlesinger argued that the New Deal’s successful establishment of the welfare state and a mixed economy meant “quantitative liberalism” should be succeeded “qualitative liberalism,” which would “fight spiritual unemployment as [quantitative liberalism] once fought economic unemployment” and “concern itself with the quality of popular culture and the character of lives to be lived in our abundant society.”

But just because the extinction of liberalism was a real anxiety among liberals, doesn’t mean that there was ever a real chance that liberals would actually pack it in. If history shows anything about the progressive mindset, it’s that there’s always more work to do. Very soon after Schlesinger offered his diagnosis of and prescription for the liberal dilemma, John Kenneth Galbraith published The Affluent Society, which in turn would lead to the Great Society programs which set about not only to transform society in myriad ways, but to do so with a sense of panicked urgency. Ever since, the new class activists in and out of government have recommitted themselves to transforming society through law and bureaucratic diktat, popular culture, and K-through-PhD indoctrination.

Not all of these efforts have been wrong or pernicious in intent or result. One of the wonderful things about American culture is that it is fundamentally bourgeois, so it tends to “bourgeoisie-ify” even the most marginal cultural trends. One need only look to see how queer—and straight—theorists who once dreamed of “smashing monogamy” now celebrate the fact that gay men and women can spend their days as committed couples raising children and working to pay of their mortgages. For all of the effort by the campus left and their emissaries in the larger culture, identity politics alone—be it racial or gender quotas, barmy historical revisionism, or grievance peddling in all of its predictable forms— is not strong or compelling enough to overpower the force of our culture or the countervailing pressure to “work hard and play by the rules” that capitalism encourages. A free society directs men’s vanity toward its proper objects: The virtues of prudence, restraint, industry, frugality, sobriety, honesty, civility, and reliability.

And this is the great and tragic irony. The hurly-burly of America’s cultural politics, while important, even vital, can never unravel the implicit social contract of capitalism which says that if you follow these virtues, you will do just fine. If you teach those values to your kids, they will do better than you. That is true of whites, blacks, Hispanics, gays, and everybody else Maya Angelou listed in her no doubt brilliant poem. That in a nutshell is the American dream. There are no guarantees, but odds are in your favor. Indeed, that’s the hitch. It’s because there are no guarantees in a free society that you develop the habits that are essential to success in a free society. Freedom makes many things harder, which is to say it makes many things more valuable.

Without wading into the nitty gritty of every policy proposal out there, the simple fact is that the Democratic agenda of “fighting for the middle class” amounts to subsidizing the middle class. Both as a philosophical goal and a cynical political strategy, FDR sought to turn vast constituencies—labor unions, blacks, widows, big business, et al.— into clients of the state. The “interest-group liberalism” he left the party with served it well politically for more than a generation, until mainstream Americans came to realize how it was undermining the health of the overall society, culturally and economically. That realization put Ronald Reagan in office.

The Democratic Party since Clinton has tried to “transcend” interest-group liberalism by treating the whole “middle class” as a monolithic interest group. From housing policy, to student loans, to health care, the philosophy driving the Democratic Party amounts to middle class social democracy. It’s not evil, and though it makes the libertarian inside me scream in agony to say it, it’s not altogether wrongheaded. A modern society does have an obligation to figure out how to care for those who cannot care for themselves, be they sick, poor, or elderly. That doesn’t require centralized, state-driven policies. Nor does it require policies that undermine the Smithian virtues. But it does require some policies.

The problem with the contemporary liberal approach is that it amounts to middle class welfare. Not only can we not afford it economically, the middle class cannot afford it morally. To miss out on the opportunity to cultivate the Smithian virtues is to eat the seed corn of social capital. Liberals don’t see it that way. They see it as an effort to make life easier, to expand the realm of “positive liberty” that John Dewey envisioned and FDR hoped to implement with his “economic bill of rights.” The liberal vision of an advanced society is one rich enough to liberate the middle class from their comfortable bourgeois lifestyles and to subsidize their conversion to bohemian ones. If you want to be a “musician or whatever,” as Nancy Pelosi said when she argued in favor of ObamaCare, it’s okay, because we’ll tax the rich enough so that you don’t have to worry about life’s essentials (like health care or housing or food or your kids’ education) anymore. In other words they are going to win their centuries’ old war on the middle class by subsidizing the bohemian lifestyle to the point where it no longer pays to be bourgeois. It probably won’t work in the long run. But in the short run, it will bankrupt us all, both financially and morally.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.