Hey,

So I’m sitting outside the Omni hotel in Oklahoma City, smoking a cigar and getting a very late start on this “news”letter. I had to deliver a lunchtime speech to the Oklahoma Chamber of Commerce, and I got back to the hotel to work as quickly as I could. I’m missing a private tour of the Cowboy Museum just for you guys—and it looked awesome.

But I’m not complaining. I love you people (well, most of you). I’m just letting you know that you should take circumstances into account when grading this “news”letter.

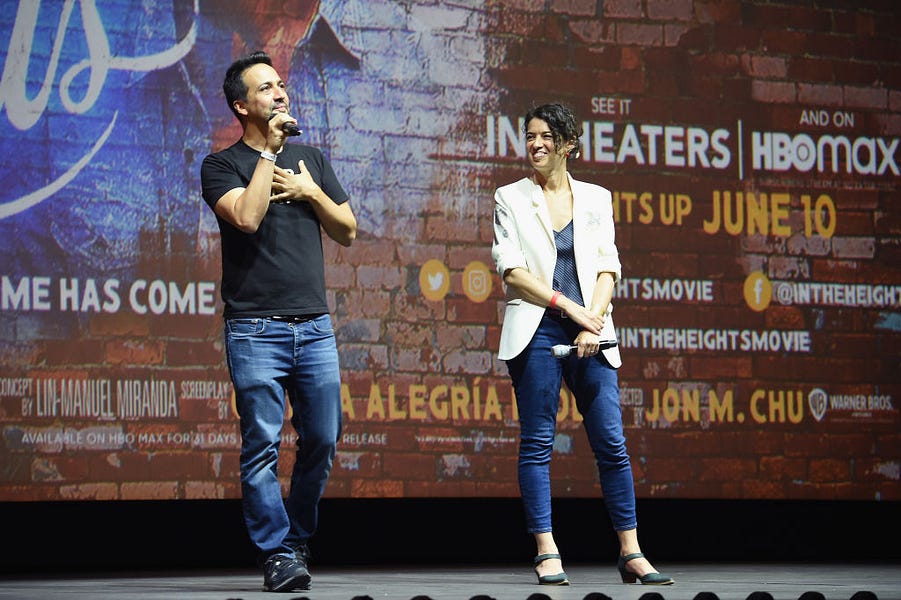

And that’s a good place to start: Circumstances matter. This morning on The Dispatch Podcast, I made a fairly strained analogy of In The Heights to the American Founding and Lin Manuel Miranda to the Founders. And remarkably, the comparison to the Founders had nothing to do with Hamilton: The Musical. Since it didn’t seem to work there, I’m gonna give it another try here.

I’ve written a lot about how the way to judge historical progress is by looking at what came before, not what you think lies ahead.

Conservatives, traditionally, see politics as being about space—realms, areas, zones, nations, communities, institutions, and yes, gardens—while progressives, traditionally, talk about direction.

This isn’t a difference between good and bad, but a difference of orientation. Obviously, though, I think the conservative approach is generally better.

But both approaches can yield terrible outcomes. If all you care about is protecting the world as it is, you’ll turn a blind eye to necessary reforms. Over time, that necessity might fester into political movements that favor radical change rather than prudent change.

Indeed, for years I’ve approvingly quoted Burke’s line, “I must bear with infirmities until they fester into crimes.” What he meant is that you need to take the world as it is and not let political zeal make the perfect the enemy of the good.

I agree with that—in principle. But as I consider it more in practice, I think there’s probably room for prudent reform of problems before they actually fester into crimes. Burke was writing against the backdrop of the unfolding revolution in France and amid a glorious tide of English Whiggism at home. But that’s not a universal context—it’s a particular one.

In the United States, it’s certainly the case that the status quo bias of conservatism contributed to the continuation of, say, Jim Crow far beyond the time infirmity had festered into crime. And if you agree with Christopher Caldwell’s indictment of the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, that just buttresses the case that conservatives should have prudentially dealt with the problems of segregation—and slavery—much earlier.

Meanwhile, the progressive race to get all of society to where you think it needs to be can lead to all sorts of terrible things. The Jacobins, Bolsheviks, and countless others eliminated all sorts of people for the simple crime of being ballasts impeding the revolutionary timetable. The new president of Iran played a major role in the execution of some 30,000 people in just five months for precisely that crime.

Okay, so let’s get back to the American Founding. For many of today’s progressives, it falls short of the mark—not just because of slavery, but for a host reasons. I say “today’s progressives,” but the truth is this has been the progressive line for more than a century. Back when Marxist (or class conscious) thinking was the height of sophistication, Charles Beard portrayed the Founders as a bunch of wealthy property owners enriching themselves. Today, that argument—debunked by countless historians—still endures. But it’s been eclipsed by an almost identical argument based on race rather than class. The Founding was “white supremacist” because it kept slavery in slave states—a tragic necessity for the ratification of the Constitution.

But what people tend to forget is the degree to which the Founding was a massive improvement over what came before it. The Founders eliminated all notions of inherited nobility and aristocracy. They enshrined freedoms of religion, speech, and assembly. The Founding was the most radical political—and epistemological—leap forward in history.

The amazing thing is that the very standards established by the Founding are used by critics to condemn it. Where do you think you got the idea of human dignity and equality in the first place? It’s as though the Founders—and enlightenment thinkers generally—bequeathed to the world a yardstick of principle that its heirs now use to bludgeon them.

Now, it’s entirely possible that one day we’ll come up with a better fundamental charter than the Constitution—as amended—but if we do, historians will draw a line from the Constitution (or the Magna Carta, or even the Code of Hammurabi) that counts the Founding as a major step forward in human history, not a hindrance.

Which brings me to Lin Manuel Miranda. The backlash to In the Heights is a case study of using some abstract notion of perfection as a cudgel to beat up the good.

The long and short of it is that he didn’t give enough roles to Afro-Latinos in proportion to their representation in the Dominican American population. This amounts to the “erasure” of dark-complexionedLatinos. As one writer puts it, the “issue goes beyond one film or one casting decision: it is about the legacies of white supremacy that have positioned whiteness as a universal experience from which we can tell stories.”

Maybe. Or maybe, the film’s producers made casting decisions based on other factors. Surely no one seriously thinks Miranda’s intent was some exercise in bigotry or “erasure.” Maybe they just did the best job they could based upon the singers and dancers available. Heck, maybe they even simply made a mistake.

But if your concern is the absence of Dominican Americans in the artistic landscape, you know what would have been worse? No movie featuring Dominican Americans being made at all. Similarly, if you were concerned with advancing the cause of human rights and democracy in 1789, you know what would have been worse than the Constitution as it was written? No Constitution being written at all!

If you think that diversity, multiculturalism, inclusiveness, or whatever is the latest term of art for such things is important, then Miranda is a hero. I don’t think you can dispute that Miranda did more than anyone else to put Latinos on the cultural or artistic map in our lifetimes. Maybe that’s wrong, and he’s just one of the top two or three people to do so. And not just Latinos: Hamilton and In The Heights created the careers of many black performers, as well.

That doesn’t mean he’s immune to criticism. But my God, do you think this backlash is going to generate more movies like In the Heights or fewer? Sure, this brouhaha might affect casting decisions for future movies—but only if such movies are made in the first place. It seems to me that the more likely outcome is that Hollywood executives will say, “Ugh, who needs the aggravation?”

Is the release of In the Heights a step forward for “inclusion”? Obviously. Is it perfect, according to that metric? Of course not—because nothing ever will be or can be. And any attempt to create art solely according to a single perfect standard will suffer as a result.

I obviously think a lot of this is an ideologically driven phenomenon. But it’s worth keeping in mind that when people weaponize utopian ideas, they usually have agendas that aren’t necessarily connected to utopianism. Various Jacobins used “prolier than thou” arguments to eliminate rivals, not advance the cause.

That’s not what these people are up to. Miranda isn’t in danger of being sent to the guillotine. But a lot of the attacks on him seem like the identity politics version of Neil Degrasse Tyson’s schtick. Justifiably or not, Tyson has earned a reputation for nitpicking movies about science or space that he didn’t consult on. It’s a brilliant protection racket for getting yourself hired as a consultant.

Again, I’m not saying all of the criticisms are illegitimate or without merit (though I am saying they’re all wildly exaggerated and counterproductive). Tyson’s tweets about how meteors behave or how spaceships explode are probably correct. But when the Washington Post corrals a bunch of black Dominican writers and artists—identified at the top of the essay to hammer the point home—who condemn Miranda’s perpetuation of “White hegemony,” or when the New York Times uses the controversy as an argument for more representative hiring practices, it’s hard not to see at least a dual purpose to all of this.

One last point: It’s just a lighthearted movie, for God’s sake.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.