Happy Friday! Republican lawmakers beat their Democratic counterparts 10-0 in last night’s Congressional Baseball Game, ensuring the GOP presidential nominee will have home-field advantage in the 2024 debates.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

The Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday that real gross domestic product decreased at an annual rate of 0.9 percent in the second quarter of 2022.

-

President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke on the phone for more than two hours on Thursday, warning each other not to disrupt the status quo over Taiwan. Xi reportedly warned that “those who play with fire will perish by it,” while Biden reiterated the United States’ longstanding policy with respect to the island remains unchanged. The leaders also discussed climate change and health security, according to a White House readout.

-

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear announced Thursday at least eight people have died in flooding after parts of the state received more than eight inches of rain Wednesday night and Thursday morning.

-

The House voted 243-187 on Thursday to advance a $79 billion package intended to jumpstart domestic computer chip manufacturing and boost the United States’ competitiveness with China. The legislation will now head to President Joe Biden’s desk, and he is expected to sign it into law.

-

The average number of daily confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States has increased about 1 percent over the past two weeks as the Omicron BA.5 wave continued to spread, while the average number of daily deaths attributed to the virus—a lagging indicator—decreased approximately 5 percent. About 37,100 people are currently hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.S., up from approximately 34,700 two weeks ago.

-

The New York Times reported Thursday the Biden administration is planning to roll out a COVID-19 vaccine booster campaign in mid-September, as Pfizer and Moderna have promised to have millions of doses of an updated, Omicron-specific vaccine ready for shipment by then.

-

The Labor Department reported Thursday that initial jobless claims—a proxy for layoffs—fell by 5,000 week-over-week to a seasonally adjusted 256,000 last week, remaining close to the highest level this year as the tight labor market continues to slacken.

BBBack From the Dead

Turns out harassing someone incessantly for months on end is actually a pretty effective way of getting what you want. Well, 12 percent of what you want, at least.

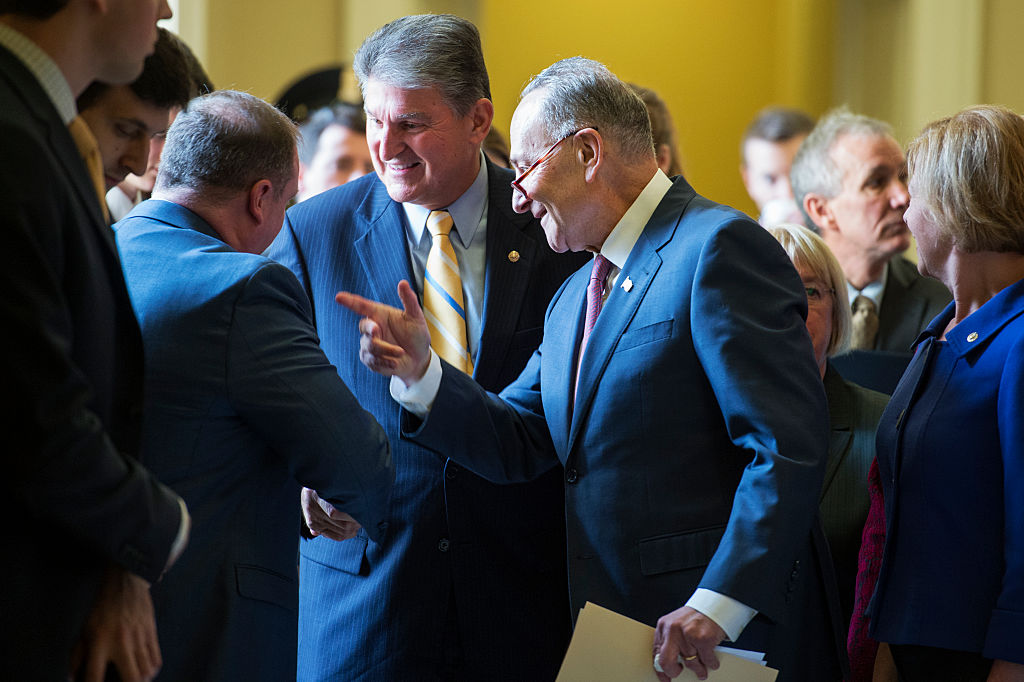

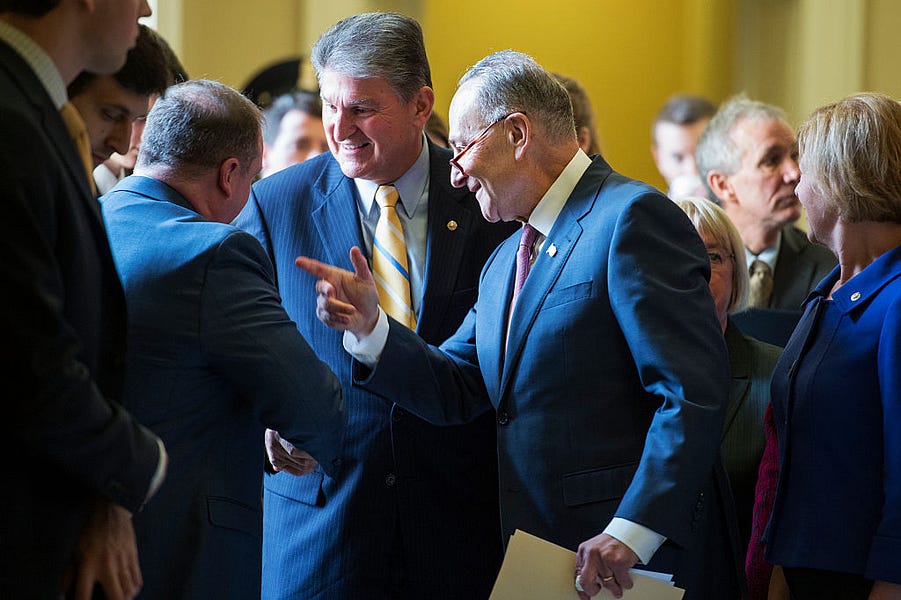

Sen. Joe Manchin shocked the political world on Wednesday evening by announcing he had reached a deal with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer on a pared down version of the Build Back Better Act he essentially killed in late December, rebranding the legislation for the times as the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

“Build Back Better is dead,” Manchin said in a lengthy statement explaining his decision. “Rather than risking more inflation with trillions in new spending, this bill will cut the inflation taxes Americans are paying, lower the cost of health insurance and prescription drugs, and ensure our country invests in the energy security and climate change solutions we need to remain a global superpower through innovation rather than elimination.”

After months of toying with supporting Democrats’ massive, $3.5 trillion reconciliation package last fall, Manchin ultimately pulled the plug days before Christmas, citing his concerns about inflation (then a measly 6.8 percent!) and the national debt. Democratic leaders had been working behind the scenes with the West Virginian ever since to bring some version of the climate and social spending legislation back to life, to no avail. Talks appeared at a standstill as recently as two weeks ago.

But Democrats finally came to grips with the current Senate math, and essentially told Manchin to write up a bill of his own that he could support. So he did.

The Inflation Reduction Act is significantly smaller than its predecessor, stripping out Build Back Better’s government-funded preschool, extended child tax credit, guaranteed family and medical leave, affordable housing subsidies, and more. Instead, it drills down on two areas: healthcare and climate change.

If enacted, the 725-page bill would extend federal subsidies for low-income Americans’ Affordable Care Act premiums for three years and allocate $369 billion in climate spending—primarily in the form of subsidies and tax credits incentivizing U.S. consumers and businesses to shift to renewable energy sources over the next ten years. Low- and middle-income Americans, for example, would receive a $4,000 tax credit if they bought a used “clean” vehicle, and up to a $7,500 tax credit if they bought a new one. About $30 billion is set aside for grants and loans that would go to states and electric utilities so they can “accelerate the transition to clean electricity,” and more than $20 billion in grants and loans would be made available to auto manufacturers to retool existing factories—and build new ones—to pump out clean cars. Democrats have touted the package as the “single biggest climate investment” in American history, and claim it would put the United States on a path to cut emissions 40 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. (We’re currently on track to cut emissions by about 20 percent.)

Unlike the Build Back Better Act—which relied on gimmicks to artificially reduce its topline costs for accounting purposes—the Inflation Reduction Act is actually fully paid for. It would implement a 15 percent minimum tax on corporations earning in excess of $1 billion in profit—essentially eliminating deductions intended to incentivize capital investment and research and development—and chip away at the so-called “carried interest loophole” that allows wealthy investment managers to reduce their tax burden by classifying some of their earnings as capital gains rather than regular income. The legislation would also boost IRS funding by $80 billion over the next decade—in the hopes tougher enforcement would generate additional tax revenues—and save the government some money by allowing Medicare to negotiate the price of certain prescription drugs starting in 2026.

According to Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation estimates provided by Democratic leaders, the legislation would generate $739 billion in revenue over ten years and spend $433 billion, reducing the national debt by more than $300 billion over that span. Some economists aren’t quite so sure.

“It will probably reduce the deficit, but not by as much as we’ve been told, because the three-year extension of the Obamacare subsidies will almost surely be extended again in three years and eat away some of the savings,” Brian Riedl—a budgetary expert at the Manhattan Institute—told The Dispatch. “These numbers are also based on the assumption that the tax gap money will come in. The Congressional Budget Office is assuming that for every dollar spent on tax enforcement, they will collect two and a half dollars in extra tax revenue. Some have suggested it could be more, some have suggested it could be less. We just don’t know, and that’s a wild card in the score as well.”

And will the bill actually take a bite out of inflation as its title suggests? Possibly, but not necessarily in the most efficient way. “To the extent that this bill reduces inflation, it will be in large part by slowing down the economy—and there are probably better ways to reduce inflation,” Riedl said. “They could have gone after tariffs, encouraged oil and gas exploration, opened up the ports. There’s so many other things they could have done to reduce inflation in a pro-growth manner.”

“There’s never a good time to raise taxes, but the worst time to do it is when the economy is softening and likely heading into a recession,” he added.

Democrats have had Lucy pull the football away on this legislation enough to know not to celebrate until President Biden has signed it into law. The Senate parliamentarian is still working through the text to determine whether it abides by the reconciliation rules that would allow Democrats to bypass the filibuster and pass it along party lines. Pharmaceutical and energy industry lobbyists are preparing an all-out blitz. Other Democrats are already angling to wedge their priorities back into the trimmed down bill. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema—another Democratic moderate—is reviewing the legislative text before committing to support it, according to a spokesperson. Even if she does, Sen. Dick Durbin just contracted COVID-19—and Democrats will need all 50 senators present and voting yes to get the package over the finish line. Lawmakers are reportedly hoping to vote on the package the week of August 8.

Biden had little to do with negotiations on the deal—Manchin said “it could have absolutely gone sideways” if the White House got involved—but the president delivered a speech on Thursday celebrating the “historic” agreement and urging senators to get it to his desk. “Look, this bill is far from perfect. It’s a compromise,” he said. “But it’s often how progress is made: by compromises.”

Recession Storm Clouds Gather

The second quarter’s gross domestic product (GDP) numbers arrived Thursday, and one thing’s clear: The American economy is definitely in a recession, unless maybe it isn’t.

We’ll back up.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday that seasonal and inflation-adjusted GDP fell at an annual rate of 0.9 percent in the second quarter, marking a second consecutive quarter of contraction, since real GDP fell at a 1.6 percent annual rate in the first three months of 2022. And while seasonal inventory swings and sagging external demand dragged down Q1’s GDP number, the second quarter showed a broader weakening of domestic demand thanks to inflation, rising interest rates, and high energy prices.

Two back-to-back quarters of economic contraction is a common shorthand for declaring a recession, which is why plenty of Republicans are happily using the R-word to hammer the Biden administration on its economic policies. “Democrats inherited an economy that was primed for an historic comeback and promptly ran it straight into the ground,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell alleged yesterday.

Biden administration officials have referenced that two-quarter rule in the past. National Economic Council Director Brian Deese did so in 2008 as the economic policy director on Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign; Council of Economic Advisers member Jared Bernstein did so in a 2019 op-ed. This week, however, they’ve been opting for a more official classification.

“Two negative quarters of GDP growth is not the technical definition of recession. It’s not the definition that economists have traditionally relied on,” Deese said Tuesday. “There is an organization called the National Bureau of Economic Research, and what they do is they look at a broad range of data in deciding whether or not a recession has occurred.”

Technically speaking, he’s correct. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)—a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization—has a Business Cycle Dating Committee that is considered an authoritative source for declaring a recession, and its definition includes a lot more moving parts than just two quarters of contraction, like sustained downturns in spending, employment, income, manufacturing, and more. The body generally waits until months after a recession begins to formally declare one, as initial GDP numbers are preliminary estimates, and are often heavily adjusted as more data comes in. There’s a chance, however small, that such a modification will reverse this quarter’s apparent contraction.

There’s an obvious reason Biden administration officials are relying on the NBER definition this time around, but arguments we’re not yet in a recession aren’t entirely without merit. Consumer spending continued to increase in Q2—albeit at a slower rate than in Q1—and unemployment remains near record lows. U.S. employers have added an average of 456,000 jobs per month in 2022, though that pace has decelerated in recent months as well.

“Coming off of last year’s historic economic growth—and regaining all the private sector jobs lost during the pandemic crisis—it’s no surprise that the economy is slowing down as the Federal Reserve acts to bring down inflation,” President Joe Biden said yesterday. “[But] we will come through this transition stronger and more secure. Our job market remains historically strong, with unemployment at 3.6% and more than 1 million jobs created in the second quarter alone.”

But even if we aren’t yet in a NBER-approved recession, odds are we will be in short order. The Federal Reserve hiked interest rates another 75 basis points on Wednesday, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell has indicated the central bank won’t hesitate to tip the economy into recession if that’s what it takes to tame inflation. “There would be the risk of doing too much and imposing more of a downturn on the economy than was necessary,” he said Wednesday. “But the risk of doing too little and leaving the economy with this entrenched inflation, it only raises the cost … of dealing with it later.”

In many ways, the entire recession debate is irrelevant, as, whether the economy meets a specific threshold or not, Americans feel lousy about it. Gallup’s Economic Confidence Index is at its lowest level since 2009, and a whopping 85 percent of respondents in late June believed conditions were worsening. Nearly two in three respondents in a CNN poll earlier this month said they believe the economy is already in a recession. “Why do so many Americans feel so bad about the economy? Inflation burns,” KPMG chief economist Diane Swonk wrote recently. “What we achieved with rising wages when we emerged from initial lockdowns was quickly lost to the fires of inflation.”

“Whether the economy meets the conventional or formal definition of recession is in many respects immaterial,” wrote Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at accounting firm RSM US. “Either way, households and firms are reeling from combined energy, inflation, and rate shocks that have damped individuals’ purchasing power and are in the process of reducing household living standards. That is the toll levied by the inflation tax and is why it is critical to restore price stability to the economy as soon as is reasonably possible.”

A Quick Clarification on Monkeypox

In yesterday’s TMD, we wrote that monkeypox is “primarily, though not solely, sexually transmitted,” noting that, although monkeypox “can spread through non-sexual contact—holding a child, for instance, or touching dirty linens—98 percent of global cases discovered thus far have been among” men who have sex with men.

Most of that remains true, but there’s a debate within the medical community that we did not acknowledge over whether to actually label monkeypox as “sexually transmitted.” The disease spreads through close contact—and in practice, that close contact is often sexual in nature—but it isn’t necessarily an STD in the ordinary sense. According to the CDC, it’s currently unknown if monkeypox can spread through semen or vaginal fluids.

“It’s the close contact that matters, not the sexual activity itself,” University of Edinburgh epidemiologist Dr. Rowland Kao said.

Why is this distinction important? First, people should not assume contraception can prevent transmission of monkeypox like it can with other STDs—any sort of skin-to-skin contact could lead to an infection. And second, just because the current outbreak is concentrated among gay men, that does not mean all outbreaks of the illness will be.

Worth Your Time

-

Did a 37-year-old neuroscientist at Vanderbilt University just upend everything we thought we knew about Alzheimer’s? In an exposé for Science Magazine, Charles Piller tells the story of Matthew Schrag, the man who discovered that a landmark 2006 study of the cognitive disease may have been an elaborate mirage. “Schrag’s work, done independently of Vanderbilt and its medical center, implies millions of federal dollars may have been misspent on the research—and much more on related efforts. Some Alzheimer’s experts now suspect [University of Minnesota neuroscientist Sylvain] Lesné’s studies have misdirected Alzheimer’s research for 16 years,” Piller writes. Several top Alzheimer’s researchers “concurred with [Schrag’s] overall conclusions, which cast doubt on hundreds of images, including more than 70 in Lesné’s papers. Some look like ‘shockingly blatant’ examples of image tampering, says Donna Wilcock, an Alzheimer’s expert at the University of Kentucky.

-

New York’s state legislature passed bail reform in 2019, and crime began rising in New York City shortly thereafter. A Manhattan Institute report published yesterday finds that was no coincidence. “After decades of constant, methodical decline in almost every crime category, crime in all the categories for which inmates had been released due to the new bail laws went up,” Jim Quinn, a former assistant district attorney for Queens County, writes. “In just the first two and a half months of 2020, according to NYPD CompStat reports, more than 3,000 more crimes had been committed, compared with the same period just a year earlier. That included 755 more robberies, 351 more felony assaults, 536 more burglaries, 1,221 more grand larcenies, and 532 more car thefts. The only thing that temporarily stopped the rise was the Covid pandemic—and, even then, victimization continued to increase when adjusted for the amount of time people spent, for example, in public or on the subways.”

-

As we noted earlier this week, studies have found that employees generally prefer to work from home—and providing them the option tends to boost productivity. That doesn’t mean companies should do it, Peggy Noonan argues in the Wall Street Journal. “The primary location of daily integration in America—the coming together of all ages, religions, ethnicities and political tendencies, all colors, classes and conditions—has been, during the past century, the office,” she writes. “It is where you learn to negotiate relationships with people very different from you, where you discover what people with different experiences of life really think. You discern all this in the joke, the aside, the shared confidence, the rolled eyes. And with all this variety you manage to come together in a shared, formal mission: Get that account, sell that property, get the story, process those claims. Daily life in America happened in the office. If it doesn’t, where will America happen?”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

The CHIPS Act is far from perfect, Klon argues in this week’s edition of The Current, but it’s still worth passing. “The bill ignores broader semiconductor supply chain security,” he writes, acknowledging concerns about Chinese intellectual property theft. “But CHIPS also helps the United States go on offense, incrementally improving our ability to shape the industry as a whole and to constrain semiconductor manufacturing in China.”

-

On Thursday’s episode of The Dispatch Podcast, Sarah was joined by Mo Elleithee—executive director of Georgetown’s Institute of Politics—for a conversation about the IOP’s new Battleground Poll. Most Americans believe the state of our politics is “really bad,” but do they agree on why? Plus: Alaska’s unique primary system, and will Iowa still go first in 2024?

-

And on today’s episode of The Dispatch Podcast, Sarah, Steve, Jonah, and David are back to discuss big pieces of legislation coming down the pipeline. Will the Inflation Reduction Act find footing in the House? Is the United States in a recession? And is President Biden going to run for reelection?

-

The next episode of The Dispatch Book Club (🔒) is out! Today, Sarah is joined by Annie Murphy Paul, author of The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain, to discuss what it means to live in a brainbound society. Contrary to popular belief, our brains are not actually computers—but how can we make them rise to meet the moment in this technological age?

-

On the site today, our intern Mary Trimble is double-dipping with one piece looking at the effect of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health on rural Democrats and another—co-written with fellow intern Augustus Bayard—on whether the price of copper actually serves as an economic bellwether. And Samuel J. Abrams writes about the issue of antisemitism in higher ed.

Let Us Know

What’s your snap reaction to the pared-down Manchin spending proposal?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.